Sunday Feb 15, 2026

Sunday Feb 15, 2026

Saturday, 24 October 2015 00:20 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Gal Viharaya

By D.C. Ranatunga

Polonnaruwa is to get a facelift. Launching the ‘Pibidena Polonnaruwa’ – ‘Awakening Polonnaruwa’ – development plan a week ago, President Maithripala Sirisena, who himself hails from there, lamented that the area had been neglected over the years and needed to be revamped.

The second capital of ancient Lanka after Anuradhapura, Polonnaruwa is a World Heritage Site and forms part of the UNESCO-sponsored Cultural Triangle.

Glancing through historical records of the old city, it was interesting to find top-rung officials of the now defunct Ceylon Civil Service referring to the country’s early history in their official reports.

In his Report of the Census of 1901, Head of Census Ponnambalam Arunachalam states that from the seventh century CE, the Tamil influence remained supreme in Anuradhapura till around 769CE, about the time of the invasion of Spain by the Saracens. The city was then abandoned to the Tamils and the capital transferred to Polonnaruwa or Pulastyanagara, the site probably of a prehistoric city named after Pulastya, the grandfather of Ravana.

Polonnaruwa soon rivalled Anuradhapura in magnificence. But the Tamil inroad continued and about the time of the Norman conquest of England, the Sinhalese king was taken captive and Polonnaruwa was made a vice-royalty of the Chola kings of India.

Superintendent of Census A.G. Ranasinghe in his Report of Census of Ceylon 1946 goes into more detail on the Polonnaruwa era. He refers to how Sinhalese rule was gradually re-established in Polonnaruwa when a heroic prince from Kataragama in Ruhuna “employing the four stratagems of war (sowing dissension, sudden attack, negotiation and buying off) with great cunning for the destruction of the Cholians who forcibly held the Raja-rata”. He was Kirti who came to be known as Vijaya Bahu I (1055-1110).

“It was fortunate for the country that Vijaya Bahu was long-lived. A revolt of the nobles was crushed. Order was restored. Justice which had long been neglected he caused to be administered according to law. Taxation was according to equity. Himself a poet, he was a patron of men of letters. He aligned himself with Kalinga and Pandya against the Cholians whose King was refused the hand of his sister, and for the invasion of whose country he made elaborate preparations, which, could not be carried out owing to the mutiny of part of his forces. He established contacts with new countries to the East of the Bay of Bengal, the Ramanna provinces of Burma between Arakan and Siam, where Buddhism was flourishing, and he invited and established in Ceylon a fraternity of Burmese monks. To him too is attributed the Endowment of Gilimale for the benefit of pilgrims to the Shrine of the Sacred Footprint on Adam’s Peak.”

Polonnaruwa, however, is synonymous with King Parakrama Bahu I (1153-86), referred to as Parakrama Bahu the Great, acclaimed by historians as the greatest of Sinhalese Kings. “An adept in all the arts of statesmanship and war, his happy genius followed every track with like success,” says Arunachalam.

“He re-conquered Ceylon from the Tamils and established peace, so that, as an inscription at Dambulla records, ‘even a woman might traverse the Island with a precious jewel and not be asked what it was’. He carried his victorious standards into South India, Cambodia and Siam. Vast ruins, still extant’ but rarely visited, bear witness to his power and piety. His career, fit theme for an epic poem, is hardly remembered save by the antiquarian. When shall a Sinhalese Valmiki arise to sing the story of Parakrama’s glorious life and fix it among the imperishable traditions of the Sinhalese race?”

While bringing back the whole country under his kingdom, Parakrama Bahu built huge irrigation tanks and religious buildings and unified the sangha. He fortified and enlarged the city and adorned it with palaces and pleasure gardens.

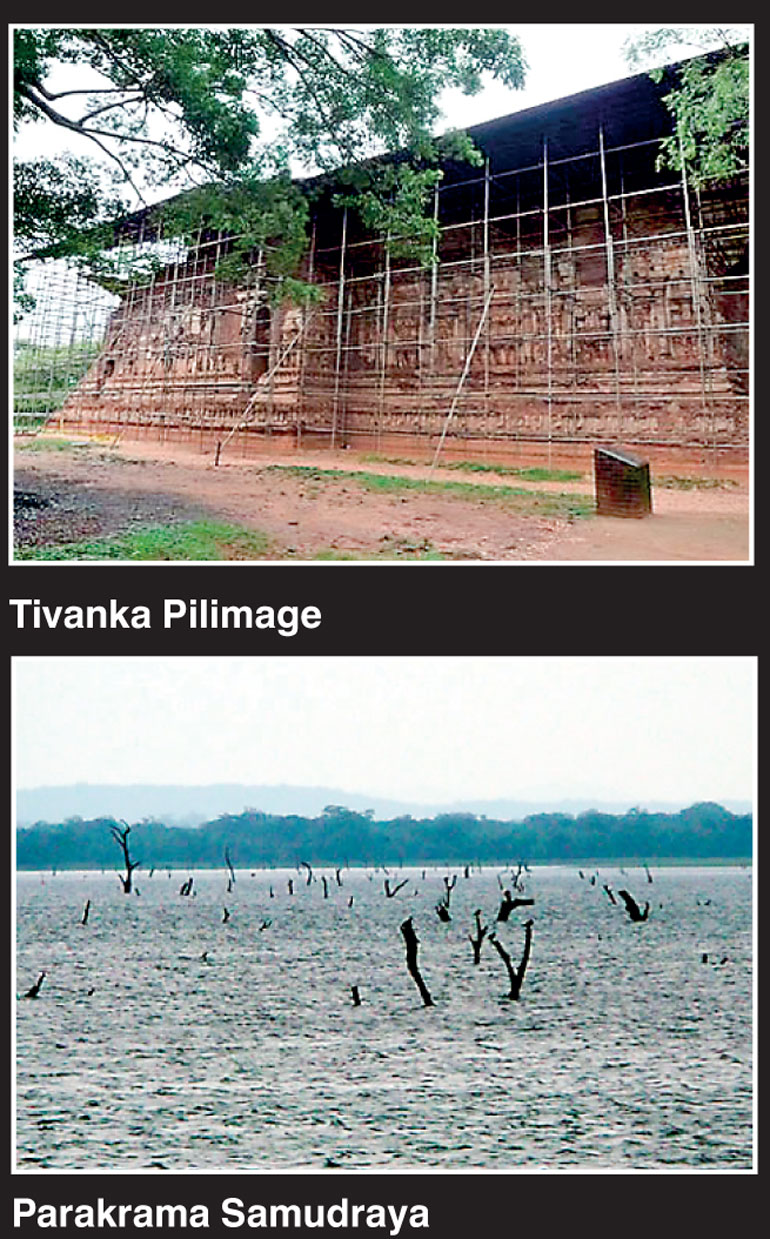

Parakrama Samudra – the sea of Parakrama – remains a lasting monument to his memory. Covering 2,400 hectares, this giant reservoir is the largest created during the medieval period. It has an embankment 12km in length. It is said that blocks of stone weighing 10 tons each were used in the constriction.

Who is he?

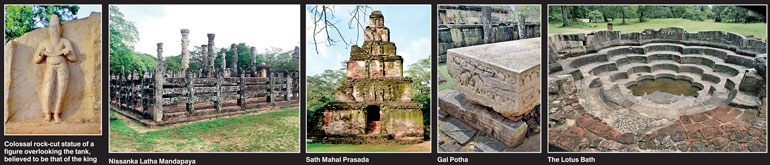

The colossal rock-cut statue of a figure overlooking the tank is believed to be that of the king although it is being argued that it does not necessarily be so, even though it has been accepted that it represents a king. Professor Senarat Paranavitana states: “In its majesty and dignity, its embodiment of power and self-reliance with which these characteristics have been expressed, it proclaims itself to be the work of a master. It is obviously not a type, as are most works of Indian art, for there is definite striving after the representation of individual characteristics in the physiognomy.”

To John Still it represents a strong old man with a thick beard and long moustaches. “On his head is a comical cap and in his hands an ola (palm-leaf) book. It is the figure of a sage or philosopher, but it has been christened Parakrama Bahu entirely at random, and even without the shadow of a probability. Standing with the open book on his hands, this fine old man has something majestic in his look and the statue is a piece of work with many conventional figures of the Buddha.”

Another fine example of sculpting is the Gal Vihara where four Buddha statues and attendant sculptures cut from a single rock represent the finest achievement of the local sculptor. In the perfectly carved statues Buddha is seen in the three positions – reclining (14m in length), seated and standing (8m tall).

“The consummate skill with which the peace of the enlightenment has been depicted, is an extraordinarily successful blend of serenity and strength, has seldom been equalled by any other Buddha image in Sri Lanka,” states historian Dr. K.M. de Silva in ‘A History of Sri Lanka’.

A third king of note who reigned from Polonnaruwa was Nissanka Malla (1187-96), the first king of the Kalinga dynasty who succeeded Parakrama Bahu. He continued from where the previous ruler left and built several religious edifices which adorned what came to be known as the Quadrangle.

The Quadrangle

The Quadrangle – a collection of temples and stupas at the centre of the city – has been described as among “the most beautiful and satisfyingly and proportioned buildings in the entire Indian world” by Benjamin Rowland, Professor of Fine Arts at Harvard in ‘Architecture of India’.

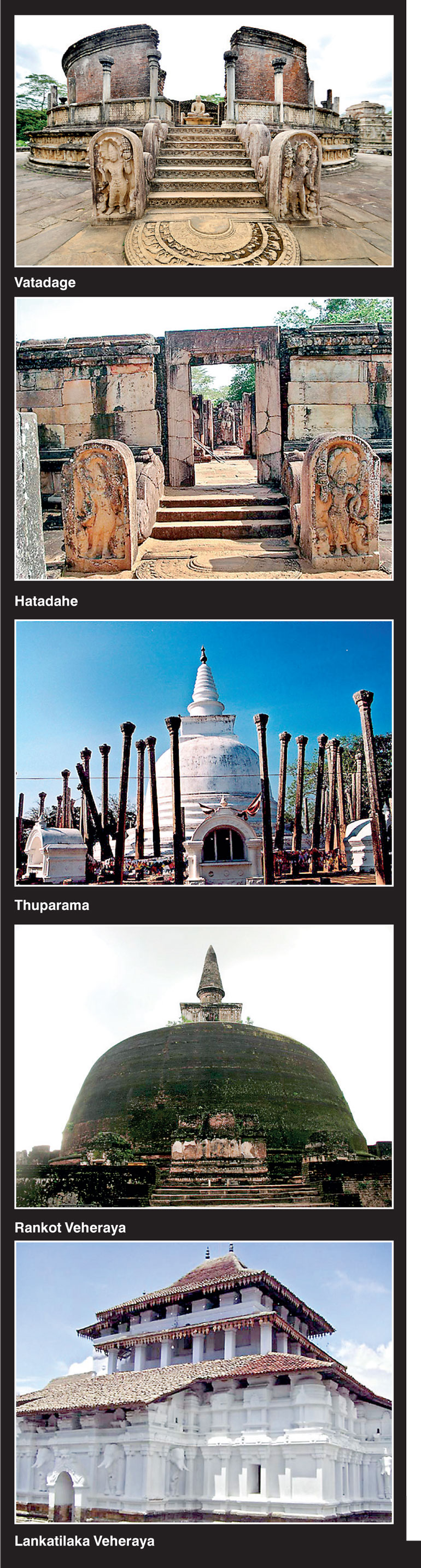

In the Quadrangle are the ‘Atadage’ and ‘Hatadage’ – believed to have been built by two kings to house the Tooth Relic. The ‘Vatadage’ is a circular building with Anuradhapura style guard-stones at the entrances with a Buddha statue straight ahead as one climbs the steps.

The ‘Sath Mahal Prasada’, as the name suggests, is a building with seven storeys each a receding replica of the other. The small top storey had resembled a box.

The ‘Nissanka Latha Mandapaya’ is a pavilion with curving pillars with a unique architectural design. It is a cluster of granite columns shaped like lotus stems with capitals in the form of opening buds within a raised platform. King Nissanka Malla is credited with building it for him to sit and listen to ‘pirith’ and sermons.

The ‘Thuparama’ is not a stupa as the one bearing the same name in Anuradhapura. It is an oblong hall with huge walls 25m tall, 15m wide with brick walls about 2m thick.

The ‘Rankot Vehera’ forms part of the Alahena Pirivena Complex along with the ‘Baddhasima Pasada’, a convocation hall where the monks met.

The ‘Gal Potha’ is a slab of granite 8m by 4m with inscriptions.

Outside the Quadrangle are more buildings, with only the walls remaining in most of them. They have been colossal buildings. The walls of ‘Lankatilaka’ and the ‘Tivanka Pilima-ge’ (image house) are decorated with paintings most of which are faded.

The Lotus Bath resembles a lotus where the floor is scalloped like the eight petals of the lotus flower.

What is left of King Nissanka Malla’s Council Chamber indicates a hall on a three-tiered stone platform. A well preserved moonstone is seen at the entrance. The king had sat on a lion throne at the head of the chamber with his ministers, generals and other officials seated on either side.

The Polonnaruwa kingdom did not last long ending with Magha (1215-36). Threatened invasions from South India forced the kings to abandon Polonnaruwa and move to safer areas. Thus the next three ruled from Dambadeniya.