Friday Feb 20, 2026

Friday Feb 20, 2026

Saturday, 12 March 2016 00:10 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Text and Pix by Shiran Illanperuma

Text and Pix by Shiran Illanperuma

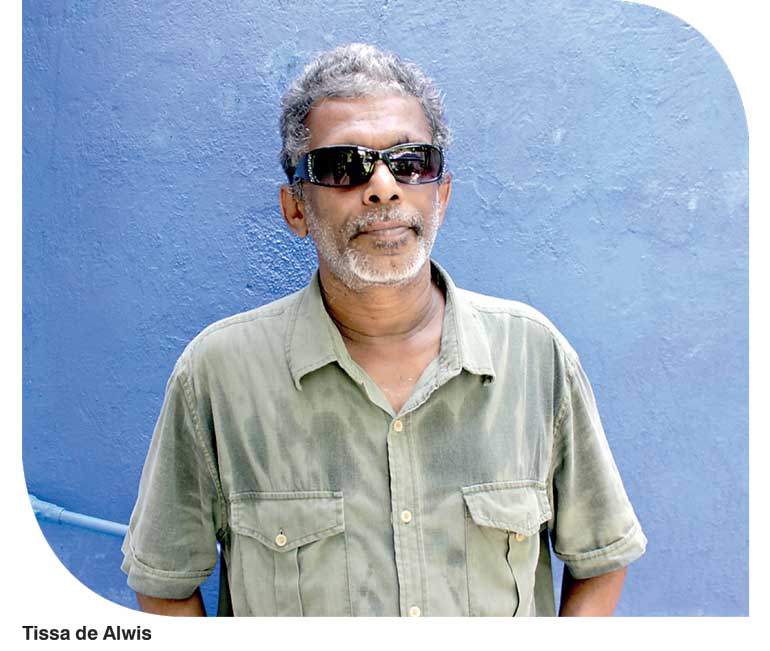

Tissa gives impeccable directions. With uncanny recall, he describes roads not by their names but by the trees, fields and buildings that surround them. A crest here, a turn there, past an old tamarind tree and it's the house with the Buddhist flag on it.

“I suppose you can just find it with this Google Maps thing if I tell you the address,” he says apologetically, at the end of his scenic verbal guide.

Tissa’s mother was a renowned Kandyan dancer, one of the first women in the field. His father, he describes as a ‘bohemian,’ not a terribly ambitious man but an intellectual sort nonetheless.

It's easy to see where this artist, film buff and amateur historian got his disposition and how his creative and intellectual pursuits were groomed.

Tissa may not dance but his work with clay – the dioramic choreography of his figures, the tactility involved in their creation – are very much in line with the raw physical presence and vulnerability expressed by dance.

His subjects meanwhile, often figures of soldiers, airplanes and assorted archaic artefacts, reflect his father's obsession with history and politics – something that was passed on to Tissa at a young age as he spent childhood hours battling through the pages of books and comics in British and American libraries.

Ask about one of his models aircrafts – made of clay and a discarded comb for the wings – and Tissa responds with a brief history of aviation and war, followed by commentary on current geopolitical affairs in the Middle East and beyond.

“It's fascinating to see how advanced aviation has become in one single century. The first flight was in 1903. A little over 10 years later, by the First World War, the aeroplane had become a weapon of warfare.” he concludes.

His brow wrinkles in an anxiety for a moment.

“You could call this whole past century as the century of warfare. Right now it has become so impersonal. Drones are being used to kill and they are being flown by pilots 6,000 to 7,000 miles away. The lines between reality and simulation have blurred, especially when you compare news footage and movies. It's very depressing to say the least.”

It’s clear that Tissa is no fan of war, despite some criticism on the contrary. “Some people think I glorify the military, but that is far from the fact. All I'm doing is looking back at history and seeing how it's being repeated,” he explains.

Indeed a great deal of Tissa’s work is undeniably militaristic. Yet there is subversion to his craft. In an age of ever-increasing complexity in military hardware, Tissa’s creations are childishly toyetic, resisting any photorealist impulse. His figures seem fragile, soft and rounded.

In many ways they reflect war as something experienced by a young boy, an object of romance and fantasy far removed from historical reality. Tissa himself bashfully talks about his boyish fascination with war, despite his moral condemnation of it.

The great elephant in the room however, is the Sri Lankan Civil War, the beast that roared to life in Tissa’s generation and rampaged for 26 years before finally collapsing under its own weight a few years ago. In fact, Tissa’s work contains little to no reference of Sri Lankan culture at all – you certainly won’t find Kandyan Kings or Tamil Tigers amidst the figures in his studio.

“It’s not that I am unpatriotic or unfeeling of my own country. As a matter of fact, even though I try to be as apolitical as possible, I'm very nationalistic. But I'm not so interested in making statements about politics or anything. A lot of my friends say that whatever you do is political but I don't subscribe to that idea,” he asserts.

“I have been called escapist by a few friends, especially for not including the Sri Lankan conflict in my figures. So maybe if I were to ask myself why this is, I would say it is maybe to a certain extent escapism because it was too close for me. Everyday there was a body count going on,” he admits, soberly.

The nostalgia instilled in the clay figures crafted by Tissa is undeniable. It's difficult not to read a profound sadness in his craft. The round beady eyes of his soldiers, the serene clay aeroplanes that seem frozen mid-glide and the horses with manes locked in a heroic wave seem to hark back to a time of childish innocence.

Indeed, what Tissa rails against is not just war but modernity and mechanisation, something he experienced right from the beginning of his adult life. His first job was stirring plaster into moulds for a ceramics corporation.

“This was a time when the ceramic industry was being mechanised. Before you had individual potters making teapots and teacups on the wheels and now things were changing. There were two to three dozen kit-wheels lying neglected because all that was being done by machines.”

“One of our old supervisors taught us how to dump a piece of clay on these machines and we just took off from there. When we started making pots we realised it was really fun. Sadly this is not done anymore and today things have advanced to the point of 3D printing, making handmade crafts obsolete.”

Though known for his clay figures he professes a great love for photography and cinema, art forms that have in recent times also developed greatly, becoming part and parcel of modern warfare as potent tools of surveillance and propaganda. In the medium’s shift from celluloid to digital is again Tissa’s anxiety over mechanisation and impersonality.

Tissa is not a fan of science fiction. “I don’t think too far ahead. I look back a lot at history and see the similarities of today where history repeats itself.”

Tissa’s animation is curbed when asked what can be done to preserve the tactility and personability of the old world. He furrows his white eyebrows in thought, but his eyes are kind.

“In my father’s words: Don't fight to change the world. Do the best you can for yourself,your family and then if you can, your country – andin that order.”