Friday Feb 20, 2026

Friday Feb 20, 2026

Saturday, 27 May 2017 01:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By D.C. Ranatunga

Gamini Jayasinghe has been traversing through the length and breadth of Sri Lanka for five decades, taking photographs of paintings in temples dating back to several centuries. These visits have taken him to some of the remotest places in the country.

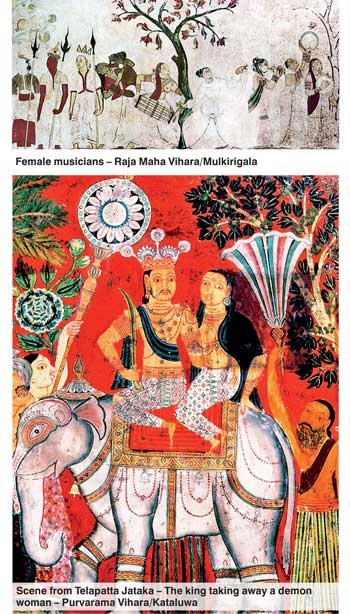

Photo-documenting some of the ancient murals was no easy task. Some places were difficult to reach. In some others the paintings were fast deteriorating. Then there was the problem of having adequate lighting. He was not discouraged by any of these. He carried on. The result is a most valuable collection of ‘The Grandeur of Sinhala Buddhist Art,’ to quote from the title of one of his publications.

A glimpse of his work can be seen at an exhibition to be held for four days from 3 June at the Lionel Wendt Art Gallery with Sampath Bank lending a helping hand.

The exhibition will unravel the progress of temple paintings in the country dating back to the time Buddhism was introduced to Sri Lanka. There is mention of how Emperor Asoka sent 18 guilds of artists, craftsmen and painters at the time Thera Mahinda came here.

It is reported that by the time Thera Mahinda passed away there was a ‘chiitasala’ – an art gallery in Anuradhapura, the capital city. The power of art to attract people to Buddhism by “showing them representations of various types of divine forms” had been accepted by the missionaries whom Asoka sent to various countries.

D.B. Dhanapala in ‘Buddhist Paintings from Shrines and Temples in Ceylon’ (1964) traces the early days of temple paintings: “The Asokan concept of promoting piety through painting, once planted in the Sinhalese mind, has lingered throughout the centuries of growth of the race, the realm and the religion. In painting, the rock surface or the temple wall was the canvas; religion the theme; and narrative, the objective. With his paint brush the ‘sittara’ (the Sinhalese artist) turned the walls into chronicles in colour in which devotees could scan the sacred stories. Art was a medium through which an exemplary life could be taught to the sinner and the sacred knowledge revived in the memory of the saint. It was primarily an attempt to present the spirit rather than the form of religion – a story rather than an idea. But the story was told in as attractive a way as possible.”

The photographs at the exhibition will give an idea to the viewer the technique used by the ‘sittara’, how stories and events have been conceptualised, how different objects have been treated, and how colours have been selected and used.

As Dhanapala points out, when the ‘sittara’ came to depict the ideal man, the Buddha, he overcame the limitations of realism by very largely ignoring them. Parts of the anatomy were exaggerated. The figure was made more than twice its normal size. The neck and shoulders became massive; the waist narrow. Bones and veins were glossed over, making the limbs round. It was a technique that created a spiritual symbol by which a man’s form could be translated into a god’s.

He writes about the choice of colours: “The preferred colours were different shades of yellow and red. Blue and green were used only occasionally to bring out the details in a design. This preponderance of yellow and red was due to the circumstances under which the ‘sittara’ worked. His canvas was a dimly lit cave surface, and his object was to fix an image in the mind of the beholder at a glance. Thus the colours had to be brilliant in order to catch the eye in the subdued light. All the figures were clearly outlined in black; the black outlines gave point and precision, and defined the figures.”

Gamini Jayasinghe’s interest in documenting rare and precious temple paintings started in the mid-1960s. In 1980, an experienced photographer by then, he undertook an assignment to photo-document temple murals dating from the 5th to the 19th century for the Lever Brothers (now Unilever) Cultural Conservation Trust. With the guidance of the Department of Archaeology, 75 temples were selected island-wide that had a full complement of wall paintings in fairly good state of preservation for photographic documentation. Advice was also obtained from the Smithsonian Institute and other organisations with similar interests, in conducting the rather elaborate task.

Done in a scientific manner, each exposure covered a defined and equal area of the total painting and incorporated a reference colour guide so that any change in the shade and intensity of the transparency could be restored to its original colour. The photographic record enables the paintings to be reproduced to perfect scale and colour and their exact location recalled using a comprehensive indexing system.

The effort took nearly five years, generating about 3,500 colour slides. They were stored at the National Archives and made available to students, historians, artists and restorers who may be interested in studying the paintings.

Gamini J’s capabilities were known to the public when his photographs appeared in ‘The Rock and Wall Paintings of Sri Lanka’ (1986) authored by Professor Senake Bandaranayake. This was followed by ‘The Buddha and His Teachings’ by Narada Maha Thera re-published attractively by Lever Conservation Trust a year later. He then planned to publish three volumes covering three distinctive periods of temple paintings in Sri Lanka. The first, on the Classical period, is covered in ‘The Grandeur of Sinhala Buddhist Art’ released in 2004. ‘Post-Classical Revival’ (2006) is the title of the publication covering the Kandyan period, with the third to cover the Modern period. He picked knowledgeable persons to write the text. They did extensive research to get the facts right. The text was written in simple language so that average reader could appreciate the great tradition and aesthetic value of the paintings.

Commenting on Gamini J’s effort of photo-documenting the paintings of the Classical era, one time Director-General of Archaeology, Dr. S.U. Deraniyagala says that his photographs bring to life in a manner that only a true professional with a feel for the subject can achieve and that his adherence to the original is exceptional.

With royal patronage during the Kandyan period, Buddhist art flourished as witnessed in a number of temples in Lankatilaka, Degaldoruwa, Medawala, Suriyagoda, Gangarama, Bamabaragala – in close proximity to the royal capital, Kandy, and Dambulla, Ridi Vihara and Kelaniya away from Kandy.

Gamini J mentions one painter – Jeevan Naide who inspired in him “a lifelong fascination with the artistic heritage of our temples”.