Friday Feb 27, 2026

Friday Feb 27, 2026

Saturday, 2 April 2016 00:10 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By D.C. Ranatunga

By D.C. Ranatunga

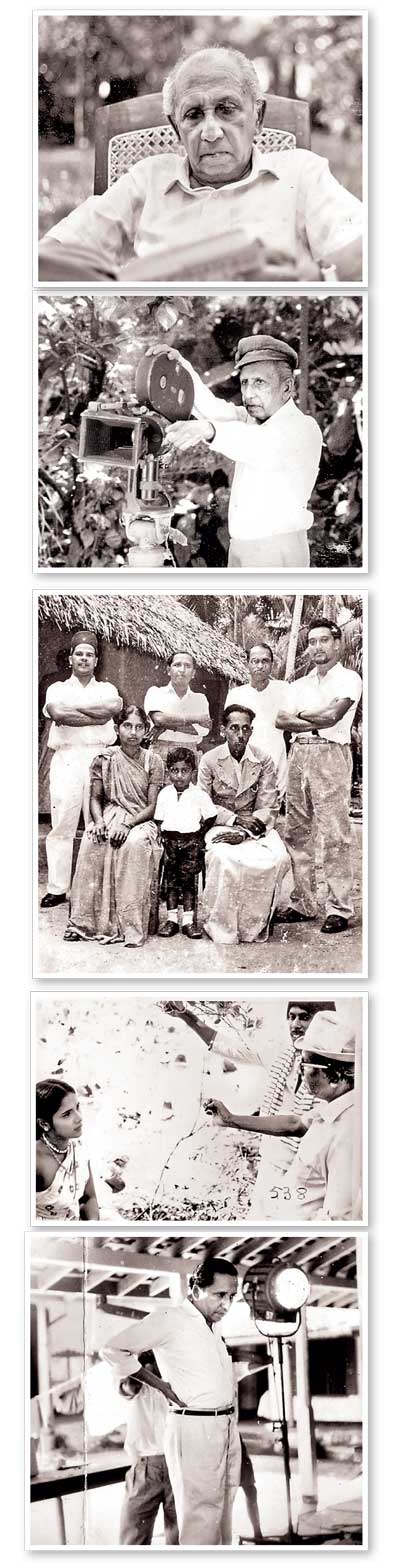

In 1965 he was the ‘Lonely Artist’. In 200 he was the ‘Formidable Genius’. Both were epitaphs used to describe Lester James Peries who celebrates his 97th birthday day next Tuesday – 5 April. Both were made at the annual International Film Festival in New Delhi.

In 1965, Lindsay Anderson said: “It was good to be able to award the salute of a Grand Prix to that lonely artist in Ceylon, Lester James Peries, whose ‘Changes in the Village’ astonished the Slavs with its elegiac, near Chekhovian grace.” That was when ‘Gamperaliya’ won the Critics’ Prize and the Golden Peacock.

In 1965, Lindsay Anderson said: “It was good to be able to award the salute of a Grand Prix to that lonely artist in Ceylon, Lester James Peries, whose ‘Changes in the Village’ astonished the Slavs with its elegiac, near Chekhovian grace.” That was when ‘Gamperaliya’ won the Critics’ Prize and the Golden Peacock.

The second occasion was the 31st Delhi Festival when he was introduced as “Sri Lanka’s most prolific and celebrated movie director whose films have given Sinhala cinema a distinct identity,” inviting him to receive the Lifetime Achievement Award by the Government of India. Captioned as the ‘Formidable Genius’ the citation stated that LJP was being honoured for “the outstanding contribution to the field of cinema and for enriching the art of filmmaking”. Krishna Kant wrote that his creative work over the past half century has “catapulted cinema from the tiny island nation into sharp international focus”.

That was not all. The following year to honour LJP further, the Indian Government commissioned seasoned documentary filmmaker Bikram Singh (he made a film on Satyajit Ray too) to do a documentary on him.

Two years later LJP became the first Asian filmmaker to be awarded the ‘Lotus Life Achievement Award’ at the Deauville Pan Asia Festival in France. A year later the Asian Film Foundation in Mumbai recognised him with the Asian Film Culture Award’ given to a “distinguished director from Asia whose contribution to cinema has been has been very significant”. This again was a ‘first’. Earlier, the Government of France had conferred ‘The Legion D’ Honeur – Commandeur Dans L’ordre Des Arts Et Des Letters’.

Continuing his ‘knack’ of collecting awards, LJP reached another milestone in his career in 2003 when he was awarded the prestigious UNESCO Felini Gold Medal at the Cannes Festival as “a tribute to his film career, which has inspired a whole generation of Sri Lankan filmmakers, and in recognition of his exceptional contribution to Sri Lankan cinema and laying the foundation for an authentic national film culture”.

At the presentation everyone was taken by surprise when a 55-minute documentary on LJP by a 22-year-old French director, Julien Plantrereux was screened as an official selection in the Special Section, one of the six sections of the Cannes Festival.

All this, of course, in addition to the ‘Sri Lankabhimanaya’ (2007) the highest civil honour, and ‘Kala Keerthi’ (1997) – the highest honour “for enriching the artistic life of the country” awarded by the Government of Sri Lanka. To mark the Golden Jubilee of the Sri Lankan cinema (1999) he received the ‘Golden Lion’ – the Presidential Award for his outstanding contribution to cinema. The University of Colombo (1995) and the University of Peradeniya (2003) conferred on him the DLitt Honoris Causa for his contribution to the cinematic art of Sri Lanka.

The Philatelic Bureau created history when a stamp was released on LJP’s 83rd birthday. This was the first occasion when a living legend in the field of arts in Sri Lanka was honoured with a stamp.

Books on Lester

In addition to these titles and honours, LJP is arguably the only Sri Lankan artiste about whom the most number of books have been written, quite apart from the regular interviews, film reviews and other news features carried in the media.

The first book to be published in English about LPJ was by journalist Philip Coorey’s ‘The Lonely Artist’ (965) described as ‘a critical introduction to his films’. By then he had done nine films. In the foreword titled ‘Working with Lester’, Reggie Siriwardena wrote: “Lester James Peries’ films have themselves stimulated the growth of a new film audience in Ceylon with new values. Like every other artist who takes a new direction, he has created the taste by which he is to be enjoyed.”

Reggie S, who did the screenplay for ‘Gamperaliya’, ‘Golu Hadawatha’ and ‘Delovak Atahra’ (the latter with Gamini Gunawardena and Tissa Abeysekera), summed up LJP’s form of direction thus: “There is one kind of film-director whose method is to impose his own personality totally on his collaborators (who become, indeed, not collaborators but executants), so that every element in his films is refracted through his own angle of vision. Lester as film-maker is not cast in this authoritarian mould. His films are undoubtedly marked by a personal idiom and style which are the vehicle of his kind of experience. But Lester achieves his unity of manner not by dictatorial imposition of his vision on his fellow-workers but by eliciting from them a like way of thinking and feeling. Working with  Lester, one realises how false (particularly in the cinema) it is the individualist notion that creation is purely a matter of personal inspiration; on the contrary, the best things often come out of discussion and exchange of ideas.”

Lester, one realises how false (particularly in the cinema) it is the individualist notion that creation is purely a matter of personal inspiration; on the contrary, the best things often come out of discussion and exchange of ideas.”

Philip Coorey saw three factors which influenced LJP when he began work on his feature films: his journalistic background (he was attached to the ‘Times of Ceylon’ in Colombo and in London), his involvement with the ‘43 Group, and his work in the Government Film Unit after his return from London. “Lester’s main cinematic involvement is with the people – their characters, their reactions, and their inner drama,” he wrote.

His journalistic skills were always visible whenever he wrote to a journal, newspaper or a film souvenir, or gave a talk. Every time I asked him to autograph a book about him, he added a short and sweet message. When I presented him with ‘The Formidable Genius’, the book I wrote as a tribute on his 87th birthday, he autographed copy for me with the words: “From the ‘Formidable Genius’ to the formidable critic and commentator who has been our artistic conscience over the years.”

Intimate portrait

The Asian Film Centre publication ‘LJP Life and Work’ (2005) by A.J. Gunawardene (one-time journalist and later Professor of English at Vidyodaya University) is described as an intimate portrait of Peries as a filmmaker, his evolution as an artist and the stories behind the making of his films.

It carries ‘An Assessment’ on LJP by Professor Wimal Dissanayake, a serious student of Sri Lankan cinema where, in his own words, he tries to locate the work on LJP in the context of Sri Lankan cinema as well as in the large context of international cinema. Wimal D highlights each of LJP’s films in the context of the development of Sri Lankan cinema.

“With the production of ‘Gamperaliya’, a tradition of serious art films was firmly established in Sri Lanka. In addition, Peries succeeded in introducing the concept of director as author. It was only with the advent of Peries into local cinema that the idea of a single authorial voice, that of the director, guiding the film came to be recognised as a significant feature of cinematic experience. In all his films, the distinct signature of Peries is unmistakably in evidence. Until the emergence of Peries as a Sinhalese filmmaker, there was no need to inquire into his authorial voice of the director as films were produced in accordance with a set formula and they were identified in terms of the actors and actresses who performed in them, and films were scarcely identified in terms of directorial authorship. What we see in Peries is a constancy of theme, content, style and vision across his total oeuvre, emphasising his authorial presence,” he explains.

To Wimal D, LJP is a filmmaker who privileges ‘witnessing’ as opposed to ‘seeing’. This carries a sense of personal involvement as well as historical consciousness that invests those social experiences with meaning. Wimal D quotes ‘Sandesaya’ (1960), ‘The Gold King’ (1975) and ‘Veera Puran Appu’ (1976) where LJP was far more successful in exploiting contemporary history than in recounting past history.

While concluding that ‘Nidhanaya’ (1970) is LJP’s most accomplished film, to Wmal D it is “a gem of a piece”. “‘Nidhanaya’ demonstrated very clearly that Sri Lankan cinema was capable of producing works that could hold their own with the best anywhere in the world. This is a stylish, absorbing, and well integrated film, in which a stern aesthetic guides the flow of images. The filmmaker’s accurate eyes and ears, externalise the inner conflict of a character wrestling with itself…It is a film in which pleasure gives rise to insight and insight into wisdom,” he writes. Incidentally, ‘Nidhanaya’ was chosen as the best Sinhala film produced during the first 50 years of Sri Lankan cinema.

Lester by Lester

It was a lifetime experience for Kumar de Silva who, for five years, recorded LJP’s story on a Sony Dictaphone to produce ‘Lester by Lester as told to Kumar De Silva’. (2007)

“LJP has an incredible e-l-e-p-h-a-n-t-i-n-e memory. At exactly half his age, I wish I had even half of it. Every single detail recorded in this book – every name, every place, every incident in his film making career from 1956 downwards – came so easily,” says Kumar.

Editor-turned-publisher Vijitha Yapa in a Publisher’s Note reminisced how, in 1962, when he was secretary to the St. Thomas’ Film Society spoke to LJP to get ‘Rekawa’ for a weekend screening. “He readily obliged and I met him at his abode which was near the Dehiwala Convent. By then he was famous but he was very humble. Popularity had not led to a swelling of his head. He was easily approachable, friendly and in no hurry to chase you out because he was busy. Since then, each film he made exposed the talent of an amazing film maker.”

Freelance journalist Piyasena Wickremage compiled a collection of LJP’s writings in 2000, which also included a Bibliography.

Pictorial biography

As for Sinhala books in my little library, apart from Ranjit Kumar’s book on ‘Rekawa’ and Ronald Fernando’s on ‘Sandeshaya’, is Professor Sunil Ariyaratne’s creation ‘Lester – A Pictorial Biography’(2006) – the well-illustrated elegant coffee table book. The skilled writer traces the life of LJP and his work in a most readable manner. He remembers how LJP gave him a letter of appreciation after seeing his maiden effort at making a 35mm short film. When ‘Desa Nisa’ was being filmed in his school in the afternoons, Sunil helped out just for curiosity. He got invited to write the dialogues and songs for ‘Madol Duwa’.

LJP’s record of films includes 12 short films (from ‘Soliloquy’ (1949) to ‘Pinhamy’ (1979) and 19 feature films (from ‘Rekawa’ (1956) to ‘Ammawarune’ (2006). After the last film, he announced that he had officially retired from film making. However, his interest in cinema continued. And he is always close to wife Sumitra when she made films. He is also willing to chat about films and always brought back memories from his own work.

To add a personal note, I feel privileged to have known him for over four decades and I feel sad that for the past two years I have missed my morning visits to the Dickman’s road residence on 5 April to wish him, since I am now domiciled away from Sri Lanka.