Saturday Feb 21, 2026

Saturday Feb 21, 2026

Saturday, 28 November 2015 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

J.R. Jayawardene taking oaths as President at Galle Face

William Gopallawa – from Governor-General to Non-Executive President – with Prime Minister Sirimavo Bandaranaike

William Gopallawa – from Governor-General to Non-Executive President – with Prime Minister Sirimavo Bandaranaike

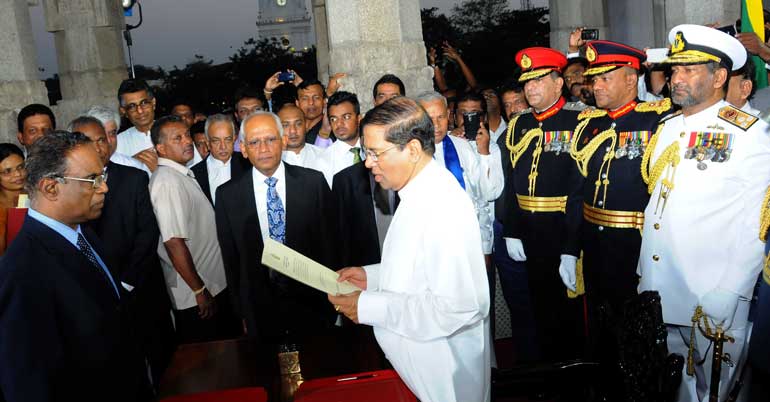

Maithripala Sirisena taking oaths as President at Independence Square

By D.C. Ranatunga

Sri Lanka’s Constitution is to be amended once again. In keeping with President Maithripala’s election promise, the Executive Presidency is to be abolished. A Cabinet sub-committee under the chairmanship of Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe is to draft the proposed amendments to the constitutions for discussion.

With the subject of a constitutional change being under discussion it may be of interest to look back on the constitutional history of the country after Independence.

Until the advent of the European powers in the 16th century, Sri Lanka experienced a monarchical system where the king ruled the country with ‘purohitas’ – ‘wise men’ – to advise him. When the Portuguese took over the administration of the maritime provinces, the King of Kotte soon became a puppet of the Portuguese and after Don Jun Dharmapala these areas were administered by the Portuguese Captains-General (1594-1658). They were followed by Dutch Governors and from 1798 by British Governors. The Kandyan kingdom continued to be under a monarch until the last King Sri Vikrama Rajasinghe was captured in 1815 and the British took over the administration of the entire country.

As a Crown Colony in the British Empire, the Governor was the Head of State representing the British monarch.

In the 67-year history after Independence, the country’s Constitution has been amended several times. There were two instances when new constitutions were promulgated.

Though Sri Lanka got Independence on 4 February 1948, the process started as early as 31 October 1945 when George Hall, the Secretary of State for the Colonies, presented a White Paper in the House of Commons with a policy statement by the British Government on ‘Constitutional Reform in Ceylon’ based on the recommendations of the Soulbury Commission.

In presenting the White Paper, he said: “His Majesty’s Government are in sympathy with the desire of the people of Ceylon to advance towards Dominion Status and they are anxious to cooperate with them to that end. With this in mind His Majesty’s Government have reached the conclusion that a Constitution on the general lines proposed by the Soulbury Commission (which also conforms in broad outline, save as regards the Second Chamber, with constitutional scheme put forward by the Ceylon Ministers themselves) will provide a workable basis for constitutional progress in Ceylon.

“Experience of the working of Parliamentary institutions in the British Commonwealth has shown that advance to Dominion status has been effected by modification of existing Constitutions and by the establishment of conventions which have grown up in actual practice. Legislation such as the Statute of Westminster has been the recognition of constitutional advances already achieved rather than the instrument by which they were secured. It is, therefore, the hope of His Majesty’s Government that the new Constitution will be accepted by the people of Ceylon.”

The State Council debated the White Paper and it was passed by a majority vote.

The Ceylon Independence Act, 1947 brought Independence to Sri Lanka. The Constitution was called the Soulbury Constitution since it was based on the recommendations of the Commission headed by Lord Soulbury. Two Orders in Council (1946 and 1947) formed the Ceylon (Constitution and Independence) Orders in Council 1947 which provided a parliamentary system of government.

Two amendments to the Constitution were made in 1954 – one to increase the number of elected Members of Parliament (MPs) from 95 to 105 following the findings of the Delimitation Commission and the other to make provision for MPs to be elected to represent those registered under the Indian and Pakistani Residents (Citizenship) Act 1949. Those referred to were really the Indian plantation workers.

Thereafter too, several other amendments were passed, of which the most significant was the one abolishing the Senate passed in October 1971.

Constituent Assembly

The United Front (UF) led by Sirimavo Bandaranaike comprising the SLFP, LSSP and CP won the general election held in May 1970 with a pledge to “carry forward the progressive advance begun in 1956 under the leadership of S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike in order to establish in Ceylon a socialist democracy”. In forming the United Front, a Common Programme had been signed by Sirimavo Bandaranaike (SLFP), Dr. Colvin R de Silva (LSSP) and Dr. S.A. Wickremasinghe (CP) on 5 June 1968.

Having got a mandate from the people at the election to draft a new constitution, the UF Government adopted a resolution by the Prime Minister for the members of the House of Representatives to form themselves into a Constituent Assembly. The Assembly was formed at a meeting held at the Navarangahala on 19 July 1970. The Speaker, Stanley Tillekeratne, was elected as Chairman. Minister of Plantation Industry Dr. Colvin R. de Silva was given the additional portfolio of Constitutional Affairs.

After much discussion, a new Republican Constitution was promulgated on 22 May 1972. In place of the bicameral legislature which was in operation since 1947, a unicameral legislature named the National State Assembly (NSA) was set up.

A titular President was to replace the Governor General. William Gopallawa who had been appointed Governor General in March 1962 by Sirimavo Bandaranaike when she was Prime Minister continued as the first non-executive president.

A Cabinet of Ministers headed by the Prime Minister was to be responsible to the NSA. Sovereignty was vested entirely with the NSA. Its term of office was to be six years. MPs who formed the Constituent Assembly were to continue as members of the NSA.

Under the new Constitution, the country was named the ‘Republic of Sri Lanka’.

The UNP came to power in July 1977 with a five-sixth majority and its leader J.R. Jayewardene became Prime Minister. On 4 October 1977 an amendment to the Constitution was passed to bring in the Executive Presidency and for JRJ to become the first Executive President.

Since the UNP had got a mandate from the people at the general election to adopt a new constitution, a Select Committee was appointed and a new constitution was promulgated on 7 September 1978. It provided for the establishment of a unicameral Parliament and an Executive President with a duration of six years for each. A system of Proportional Representation was introduced in place of the first past the post system. Parliament was to consist of 196 members. The official name of the country was to be ‘Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka’.

During the first 10 years of the new Constitution, 16 amendments had been passed. Most provisions of the Constitution could be passed by a two-thirds majority in Parliament while those relating to language, religion and reference to unitary state had to be approved at a nationwide referendum in addition to the two-thirds vote.

Resignations and expulsion of MPs of the first Parliament (Amendment 2); President seeking re-election after four years (A 3); extension of the term of first Parliament (A 4); certain public officers being qualified to contest elections (A9); Making Tamil an official language and English a link language and establishment of Provincial Councils (A 13); Extension of immunity of President/increase of MPs to 225/proportional representation and cut-off point to be 1/8 from total polled/appointment of 29 National Lit members (A 14) and making provision for Sinhala and Tamil to be Languages of Administration and Legislation (A 16) were among the amendments passed.

The 17th Amendment (Oct 2001) made provisions for the Constitutional Council and Independent Commissions during the Chandrika Kumaratunga presidency. The 18th Amendment removed the limitation of the re-election of the President to two terms of six years each, and replaced the Constitutional Council by the Parliamentary Council (Sept. 2010) during the presidency of Mahinda Rajapaksa.

President Maithripala Sirisena initiated the 19th Amendment (April 2015) to annul the 18th Amendment, replace the defunct 17th Amendment for the establishment of the Constitutional Council and Independent Commissions, and remove certain Executive Presidential powers and limit the term of office of the President to five years.

From the Manifesto

Under the heading ‘Abolishing the Executive Presidential System with Unlimited Powers’, President Sirisena’s election manifesto stated:

“The President needs the assistance of Parliament to change the post of Executive President. That is because it is Parliament which has the power to amend the Constitution. Yet the Parliament was unable to effect this change for the last 20 years. It is the President as leader of the main party who should provide the leadership to pass the required Constitutional Amendment with a two-thirds majority. For that the President should take the initiative to reach an accord among the main political parties. It is to fulfil this task that I decided to come forward as the common candidate of all the people at this presidential election.

“…In order to change the Executive Presidential System I am taking as background material agreements for abolishing the Executive Presidential system reached by the Movement for a Just Society headed by Venerable Maduluwave Sobhitha Thera as well as the proposals contained in the Draft 19th Amendment compiled by the Pivituru Hetak Jatika Sabhava headed by Ven. Atureliye Ratana Thera, which proposed a Constitutional alliance of the President and the Prime Minister. I will also consider the changes proposed to these proposals by the United National Party.

“The new Constitutional structure would be essentially an Executive allied with the Parliament through the Cabinet instead of the present autocratic Executive Presidential System. Under it the President would be equal with all other citizen before the law. I guarantee that in the proposed Constitutional Amendment I will not touch any Constitutional Article that could be changed only with the approval at a Referendum. I also confirm that I will not undertake any amendment that is detrimental to the stability, security and sovereignty of the country. My amendments will be only those that facilitate the stability, security and sovereignty of the country.”