Saturday Feb 14, 2026

Saturday Feb 14, 2026

Saturday, 13 May 2017 00:02 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By D.C. Ranatunga

Reading about the President’s plea to the Maha Sangha on the need to protect the ‘puskola poth’ – writings on ola (talipot) leaves – I was reminded of the visit to Suriyagoda temple near Kiribathkumbura close to Peradeniya a few years back. It is the temple where Most Ven. Velivita Sri Saranakara Sangha Raja got ordained and spent his early days as a ‘samanera’ – novice monk.

The temple has a cherished history for over 600 years and had been built by Suriyagoda Wijesundera Senarath Wijekoon Mudali Rajakaruna Attanayake Bandara, a highly-respected individual who was conferred the title ‘Rajaguru’ (the teacher of kings) by King Parakramabahu VI (1470-88 CE), the celebrated King of Kotte known for his scholarship and erudition.

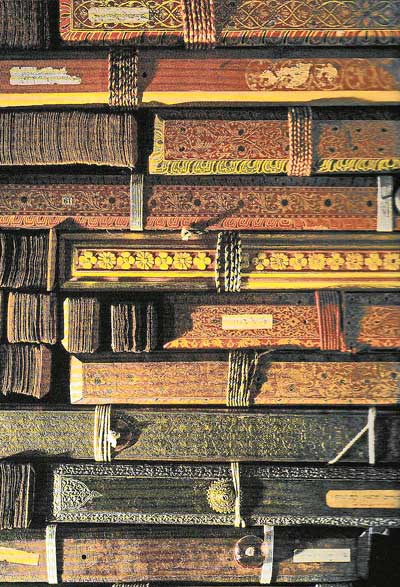

In the temple was an old almirah where a valuable collection of some of the texts used by the Thera as well as his own writings are stacked. Both the almirah and the room are kept securely locked after several attempts had been made to steal them. It was only after we convinced the resident monks that we were collecting material for a book to commemorate the 250th anniversary of Upasampada that we were shown the texts and were allowed to photograph them. (The book is ‘The Great Revival’ – a BPS publication.)

In the collection is a prized possession of the copy of the ‘Pansiya Panas Jataka Potha’ – collection of 550 Jataka tales – where the Thera in his own handwriting has written on the opening page: “In the year 2249 Buddhist Era, during the reign of King Narendrasinha, at a time when I, Velivita Saranankara Thera from Thumpane, was attempting to revive the Dhamma and the knowledge, having seen this book of Jataka tales being used as a door plank of the paddy barn in the house of Vilbagedera Rala, obtained it by replacing it with a door plank made from a forest tree. May it be known that I recorded this fact for the benefit of future generations who will then get an idea of the progress the Dhamma had made and the standard of knowledge at that time.”

By the time King Narendrasinghe ascended the throne (he reigned for 38 years – 1701-’39), Buddhism had deteriorated and the monks who were commonly known as ‘ganinnanses’, were leading a lax life virtually similar to how the lay folk lived. Buddhism was in such a perilous state that even a minimum of five higher ordained monks were not available to perform the ‘Upasampada’ Vinaya act when novice monks obtained higher ordination.

Ven. Saranankara made a valiant effort to bring back the high standards maintained earlier by going on ‘pindapatha’ collecting alms from homes and giving merit to the devotees with a short sermon. The devotees who had no way of practising the religion saw in him a ‘saviour of the Dhamma’ and eagerly awaited his arrival to collect alms. He soon came to be known as Pindapathika  Saranankara because of his regular trek for alms, a practice started by the Buddha himself.

Saranankara because of his regular trek for alms, a practice started by the Buddha himself.

Ven. Saranankara authored several books himself which form part of the collection at the temple.

The preparation of ola leaves for writing is quite a tedious process. In ‘Medieval Sinhalese Art’, Dr. Ananda K. Coomaraswamy describes how strips of the talipot palm, ‘Corypha umbraculifera’ are prepared:

“A leaf bud of the palm is cut down just before it opens; the leaf segments are separated and the midrib removed, dividing each segment into two strips. These are loosely rolled and placed in a copper cauldron with cold water and then boiled for an hour, and afterwards dried in the sun for three days. The leaves are then rolled again, this time not singly, but in rolls a foot or so in diameter.

“The rolls are exposed to the dew for three nights, after which they become pliable. In this state they can be preserved a long time, especially if kept in a smoky place, such as the loft in a kitchen. When required for use, the rolls re taken one by one and smoothed by rubbing on a polished areca stump; the trunk is tied across two posts and the olas laid across it with a stalk attached to the stalk end; the ola is then taken and pulled up and down across the trunk until it is smooth on both sides.

“The leaves are next cut up into various standard sizes, the largest three spans in length, the next and most unusual length for valuable books being two spans and four fingers; smaller sizes vary from eighteen inches downwards. Care is taken to make the strips of even breadth. All the leaves are then punched with the two string holes.

“The leaves are next strung on smooth rounded sticks passed through the string holes, in thick parcels between wooden covers; the four sides of the leaves are singed with a hot iron; the packet, now called ‘pot-gediya’, is stored until required for use. Each leaf is a ‘pat-iruva’; a gathering of eight or sixteen leaves, lettered alphabetically is a ‘pat-kattuva’ (Clough).”

Referring to writing, he says: “The leaves are removed from the packet one by one and written on with a sharp style (‘panhinda’): after the writing and revision an ink composed of ‘dummala’ oil and lamp black is lightly rubbed on (‘kalu-madinava’) with a rag and wiped with clean chaff, after which the writing stands out clearly.

“The completed book consists of the written leaves, enclosed between two wooden covers (‘pot-kambi’) of the same size and shape which are painted, lacquered, carved or quite plain. Book covers are also made of ivory, and silver. A string (‘pot-lanuva’) composed sometimes of cotton, sometimes of ‘niyanda’ fibre, and often with coloured strands, passes through one set of holes in the covers, and is wound round the book when not in use. One end of the string is attached to a flat button (‘pot-sakiya’), ivory, horn or metal, which prevents the string from slipping through the cover.”

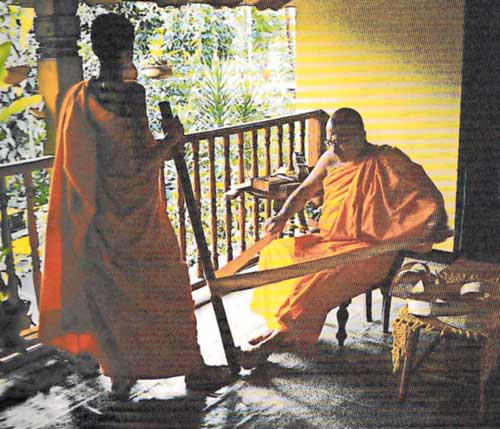

We worked closely with a monk in the Malwatta Viharaya, Ven. Kulagammana Dhammarakkhita who demonstrated how writing is done on the ola leaf. He took out a dried leaf from the place where it was stacked, unrolled it and both sides were smoothened and polished using a smooth pole to pull the cured leaf back and forth. A young monk helped in the process.

The ‘panhinda’ is made of gold, silver, copper or brass. The elaborately-carved instrument has a steel point which is used to write. The one used by Ven. Saranankara is a treasured item preserved to this day in the Suriyagoda temple.

Ola leaves have been used by native physicians in the early days to preserve descriptions of illnesses, healing methods, prescriptions and other relevant information. Astrology is another subject and horoscopes are the most popular item where ola leaves are used. Books of magic, such as ‘bali’ verses, charms and spells, have been illustrated with pictures of demons and diagrams, in plain black.

Dr. Coomaraswamy has something interesting to say on letter-writing on ola leaves. “Letters were sent on strips of ola, neatly folded, and bound with narrow strips of ola, passing once or several times round, in accordance with etiquette, as given in a verse written in Sanskrit. Translated into English, it says: “One for an enemy, two for a friend, three for a relative, four for superiors, five for father, mother, brother, six for the guru, seven for the king.”