Friday Feb 20, 2026

Friday Feb 20, 2026

Saturday, 13 June 2015 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

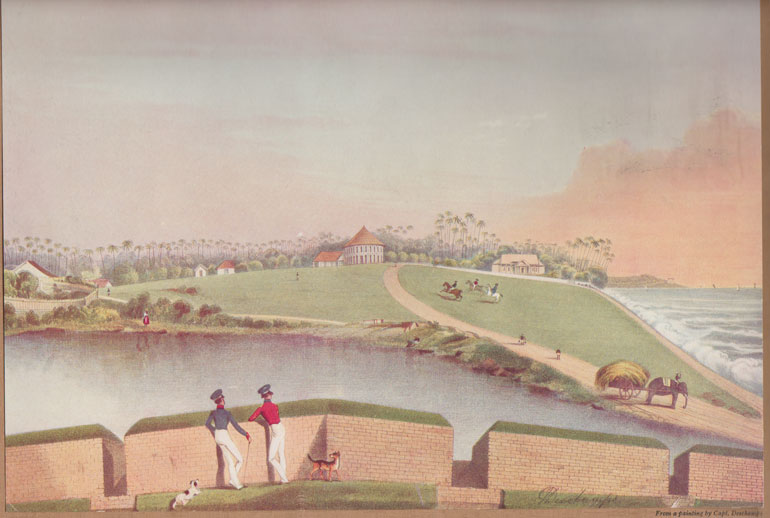

Galle Face esplanade 1845

Mango tree and the dove

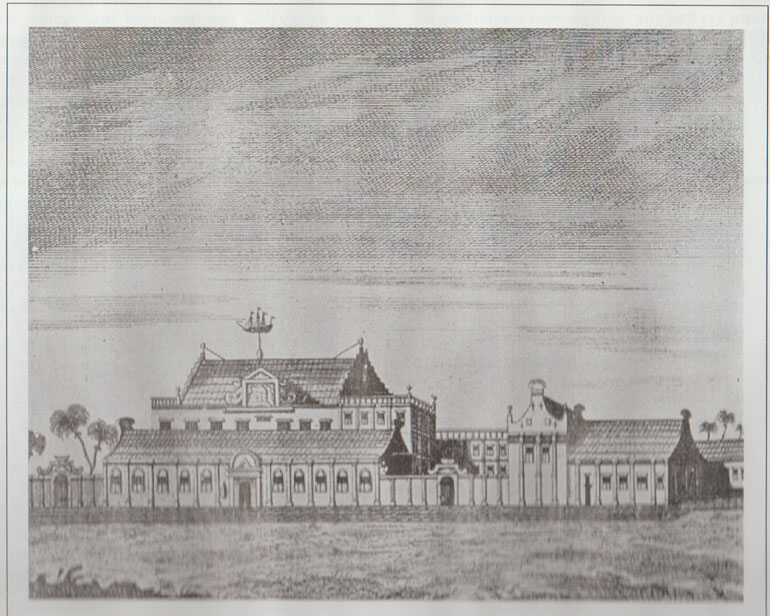

Residence of the Dutch Governor with typical Dutch architectural featuress

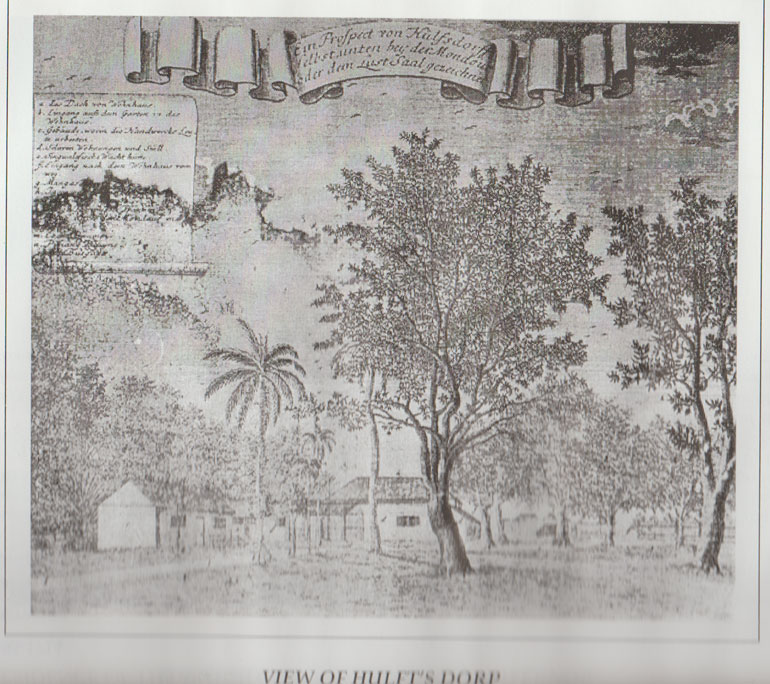

View of Hulftsdorp

By D.C. Ranatunga

The news that Colombo has hit the top spot as the fastest growing city in terms of international overnight visitor numbers prompted me to look back how Colombo gained recognition as a port city.

Colombo is mentioned as a seaport in the late Anuradhapura period (around 10/11th century) occupied by Muslims. Trade with foreign countries had been established and precious stones were exported.

Ships from China, Persia, India and Arabia had come to Colombo and berthed in the port at the bend of the sea below the mouth of the Kelani Ganga. With the spice trade flourishing, Arab traders had set up warehouses around the port with the permission of the Sinhalese king. While there were other sea ports at Kalpitiya and Chilaw, Colombo became the principal port after Kotte became the capital.

Chinese traveller Wang-Ta-Youan who came to Sri Lanka in 1330 AC described Colombo – ‘Kao-lan-pu’ as “a deep, low-lying land, the soil poor, rice and curry very dear, and the climate hot”.

Arab traveller Ibn Batuta, who was on a pilgrimage to Adam’s Peak in 1344, described ‘Calenbou’ as “one of the largest and most beautiful in the island of Serendib”.

It is recorded that in 1411, Ching Ho, the head of a Chinese expedition, carried away the Sinhalese ruler Vira Alakesvara together with his wives and children to China as retaliation for inhospitable treatment.

Several names

Colombo has been referred to by several names. To the Sinhalese, the Moorish settlement ‘Kolamba’ or ‘Kolontota’. While the Portuguese spelled the word ‘Columbo’, the Dutch, French and German maps has ‘Colombo’, as we spell it today.

According to Father Ferno de Queyroz, the Portuguese writer, “the name ‘Colombo’ is a corruption, as the true one is ‘Caleamba’ which means in the Chingala language ‘the leaf of the mango tree’.”

Robert Knox had the same idea. He writes: “…the city of Colombo, so called from a tree the natives called ‘Ambo’ (which bears the mango fruit) growing in that place; but this never bear fruit, but only leaves, which is their language is called ‘Cola’. And thence they call the tree ‘Col-amba’, which the Christians in honour of Columbus turned to ‘Columbo’. It is the chief city in the sea-coasts, where the chief Governor hath his residence.”

The Dutch adopted as the town’s coat-of-arms a mango tree with a dove (Latin: Columba).

Sir Emerson Tenant says that the city earned its name ‘Kalan-yota’ (the Kelani Ferry) from its proximity to the river, and the Moors converted the name to ‘Kalanbu’.

Scholar Julius de Lanerolle pointed out that ‘Kolamba’ (Anglised ‘Colombo’) is a Sinhalese word meaning port, ferry, harbour or haven. ‘Kolamba’ is thus a synonym for ‘tota’.In course of time ‘kolamba’ came to be fixed as the name of the principal port of the western coast.

After the Europeans

Colombo came to be recognised as an important port when King Vira Parakramabahu VIII (1484-1508), who was ruling from Kotte, gave permission to the Portuguese to build a trading station in the south-west breakwater. A chapel was also built at the same time and dedicated to St. Lawrence, who was adopted as the patron saint of Colombo.

The Portuguese coat-of-arms was inscribed on a rock in front of the bay. By 1520 the Portuguese had convinced the king that they should be allowed to erect a fort. It was first built in cabook and mud. The Moors who did not like the Portuguese constantly attacked the fort.

After constant battle, the Portuguese consolidated their position when the weak king Dharmapala ascended the throne in 1551. He was a puppet of the Portuguese and was christened Don Juan. Since it was not safe for him to be in Kotte he was transferred to Colombo, thus becoming the first king to rule from Colombo. Thereafter Kotte went into ruins and Colombo became the capital. It was referred to by the King of Portugal as “My Cidade of Colombo”.

The Portuguese and the Dutch made Colombo their centre of operations. Families were settled and the city gradually took shape as seen today. The Portuguese built a wall around the city with watch towers and bastions at various points. The main gate of the city was by the bastion of St. John, which was almost on the beach beside the fish market which until recently was the main sales point for fish in the city. They were guarded against possible attacks from the King of Sitawaka who showed aggression a few times.

After the Dutch took over in 1656, they started building bastions on more solid foundations. So were houses and other buildings. A writer once referred to the many fine buildings in Colombo – “grand mansions, lofty churches, wide streets and walks and large houses in great numbers. They were built spacious, airy and high with stone walls as if meant to stand forever.”

The British took over from the Dutch in 1796 and in1815 Colombo became the metropolis of the whole island. The administration of the city was under a Collector until 1833 when it came under the Government Agent of the Western Province.

Even nine years after the Dutch were ousted, it was noticed that the character of the city had not changed much. The Fort was occupied mainly by British residents; the Pettah – a clean and airy residential district – by the Dutch and Portuguese; the suburbs by Sinhalese, Tamil and Moorish population. The population in Colombo was estimated to be over 50,000.

There were seven bastions which were demolished in 1869 when the city walls were levelled and the moat was filled.

Place names

Until recent years when place and street names in Colombo started changing, most place names dated back to the Portuguese and the Dutch times. Mattakkuliya, for instance, is a Portuguese word which means ‘where the cooly was killed’. Possibly a cooly was killed in the area under mysterious circumstances.

They often gave names of saints to whom the churches and convents in the vicinity were dedicated.

San Sebastian Hill and St. Joseph’s Road are examples. Milagiriya had the church of Lady Miracles – ‘Nossa Senhora dis Milagres’.

Grandpass got its name from a causeway there. The Portuguese called it ‘Grand Passo’ and the Dutch ‘Pa Grande’ which eventually became Grandpass.

Kollupitiya was a great plain where the boys played. It had first been called ‘Kollan Pitiya’ which later became Kollupitiya and in English ‘Colpetty’.

Pettah being a residential area at the time obviously had streets with a lot of trees. Messenger Street, for example, was called ‘Rue de masang’ by the Dutch because there were ‘masang’ trees in plenty. That’s why in Sinhala it was ‘Masang gas vediya’.Dam Street was earlier ‘Damba Street’ due to ‘damba’ trees which grew there. Bloemendaal (vale of flowers) and Korteboam (short trees) are two more examples.

Hulftsdorp was named after the Dutch Governor Hulft. Vuystwyke Road was named after another Dutch Governor, Vuyst (1726-29).

During the time of the Dutch, Pettah was called the ‘Oude Stadd’ or old town. Pettah is an Anglo-Indian word from the Tamil ‘pettai’. It was introduced by the British. The Sinhala world ‘Pitakotuva’ gives the same meaning – outside the fort.

The British named most roads after the governors.