Monday Feb 16, 2026

Monday Feb 16, 2026

Saturday, 19 March 2016 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Himal Kotelawala

By Himal Kotelawala

The Sri Lankan leopard, or panthera pardus kotiya as it is scientifically known, is what is known as an apex predator – meaning it has no natural enemies that prey on it, for food or for sport. For thousands of years, this majestic carnivore has been sitting comfortably on top of the local food chain with no real challengers to the throne, with its kin spread over a significant portion of the island. That is, until that lethal bipedal usurper Homo sapiens started to get in its way.

Founders of the Wilderness & Wildlife Conservation Trust’s (WWCT) Leopard Project Dr. Andrew Kittle and Anjali Watson who have been carrying out exhaustive research into Sri Lanka’s leopard population for the past 15 years on Thursday presented their findings in a public presentation titled ‘The Sri Lankan Leopard – Chipping away at the truth,’ where they were able to shed some light on the many unanswered questions about the country’s only big cat that also happens to be an endangered, endemic sub-species that plays an integral role in the effective functioning of the island’s diverse ecosystems.

The duo’s research, unveiled at the presentation held on Thursday at the Met Department auditorium in Colombo, has created and maintains an ongoing database of leopard distribution data in the country and has highlighted the importance of unprotected areas and especially small, seemingly isolated forest fragments, to future leopard conservation.

According to Dr. Kittle, a zoologist who in addition to conducting research on the Sri Lankan leopard has studied the behaviour and spatial ecology of large carnivores across systems and continents including wolves in North America and lions and hyenas in Eastern Africa, the Sri Lankan leopard is a genetic subspecies different from the Indian mainland and other world populations and is only found in Sri Lanka.

“We have an improved understanding about its distribution, density, home range, social structure, behaviour, elements of diet and habitat and also an ability to estimate population size in the country,” he said.

Wild boar attacking a leopard in Yala

Wild boar attacking a leopard in Yala

Distribution

All national parks have a leopard presence, and some of these are forest reserves and therefore will have some protection. But there are leopards outside protected areas too, said Dr. Kittle.

The extent of occurrence of leopard is about 40,000 square kilometres – over 62% of the island’s total area. However, the total area actually occupied by them is only 12,600 square kilometres – less than 20% of the island.

Population density per 100 square kilometres at present is as follows:

Total density (all individuals): 21.7

(14.6 - 32.3)

Adult density: 12.1 (7.1 - 20.6)

“These are internationally high numbers, towards the higher end of the spectrum,” said Dr. Kittle.

A spatially explicit density estimate carried out by Dr. Kittle and his team using 36 detectors at an average spacing of 2163m is as follows:

All leopards:

Number of leopards – 49

Number of detections – 168

Number of occasions – 27

Mask area – 517.1 km2

Buffer – 4322m

Density – 16.17/100km2/

Adults:

Number of leopards – 33

Number of detections – 136

Number of occasions – 27

Mask area – 554.2 km2

Buffer – 4658m

Density – 8.3/100km2

“As the amount of prey available increases, the density increases,” said Dr. Kittle.

The apex-predator status of the Sri Lankan leopard, he reiterated, is a very rare case found nowhere else in the world.

“Leopards here have the same social structure as those in other parts of the world. Female ranges are based on prey availability and their ability to raise cubs. Home range should be as big as necessary but no bigger. Typically females in neighbouring ranges don’t tend to have too much overlap. Overlaying them is a much larger male range. Male ranges don’t depend on prey, but on female ranges,” he explained.

There are also transient animals, typically young males or older males that move through the system.

The Sri Lakan leopard is also nocturnal, which is unusual for an animal that doesn’t have natural competitors, pointed out Dr. Kittle.

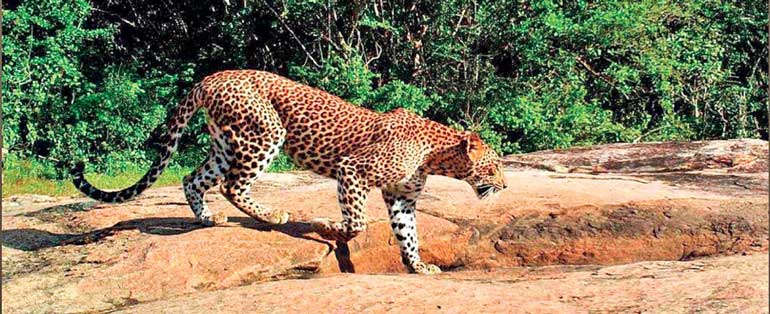

Leopard in Yala

Leopard in Yala

Sociality

In comparison to studies carried out in Africa, where over 93% of leopard sightings are solitary individuals, in Sri Lanka the figure is about 80%.

“This is a significant difference which indicates that, while leopards here may not be actually that social, they seem to be observed in groups of more than one,” said Dr. Kittle.

Again, this is due to a lack of competition.

Diet

According to Dr. Kittle, the Sri Lankan leopard has the widest ranging diet of all big cats. This, he said, allows it to exploit all types of habitats. In Yala, for example, scat analysis has shown that the most widely available prey for leopards is spotted deer. In the Central Hills, where there are no spotted deer, porcupine forms the base of the diet. In Agrapatana, about 60% of their diet is sambur.

Different habitats

In the north, where most areas frequented by leopards were inaccessible for about 27 years, surveys carried out by Dr. Kittle and his team, 85.1% of respondents had indicated there were leopards in areas they were resettling into.

“Post war development is good and necessary, but there has to be a balance between ild life and natural system preservation and development going forward,” he said.

A population estimate for the country can be arrived at by putting some of this information together (such as density estimates and distribution data for different habitats). Currently, this estimates stands between 700 to 950 adult individuals, which Dr. Kittle said needs to be fine-tuned as they carry out further habitat-dependent work in different parts of the country.

“We need to get improved population estimates. Narrow it down,” he said.

More importantly, he said, drivers of human-leopard conflict needed to be understood and threats such as poaching, fragmentation, habitat loss needed to be quantified.

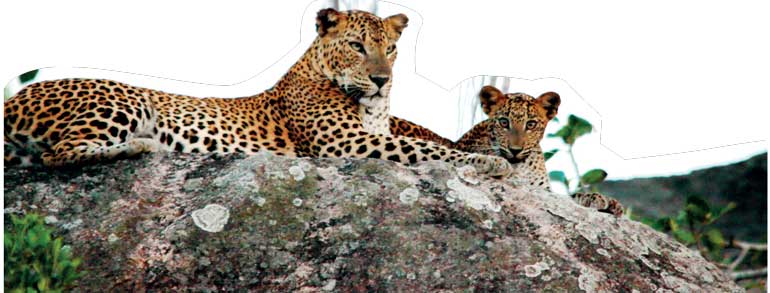

Leopard making a kill in Yala

Leopard making a kill in Yala

The Central Hills

The Central Hills is an area of keen interest to leopard researchers. It has a very high human population density with a diverse landscape mosaic that includes pines estates, tea estates, home gardens, villages, forest patches, forest reserves and other types of land.

The darker side

Unfortunately, the Central Hills also have a high incidence of human-leopard conflict.

According to Anjali Watson, whose MSc work formed the basis of the ongoing island-wide distribution and resource selection study of the Sri Lankan leopard, the changing land matrix in the area has indirectly contributed to this.

“I deal with the darker side of things: Dead leopards. As leopard researches we don’t want to be dealing with dead leopards. We’d rather be dealing with live leopards. But unfortunately over the past few years, this has been taking up a lot of our time. I dread that phone call whenever it comes and think ‘ugh, not another one,’” said Watson.

Their work has organically evolved into looking at what’s going on with regard to the ongoing human-leopard conflict and the duo are looking at ways to prevent an escalation. Their goal, said Watson, is to not be like India.

There are two types of unsavoury cases: 1) an incident, where there is an interaction between humans and a leopard, and 2) a mortality, where the leopard is actually killed or dies as a result of an interaction.

“We find that these incidents and moralities need to be verified. Finding exact information is not easy. Often, timelines are very vague. We found that a lot of the information repeat themselves sometimes, thereby giving a more alarming picture than may actually be the case. So verifying these cases and differentiating the levels of threat is important,” said Watson.

Threat levels

When dealing with the conflict, threat levels need to be assessed. The first level, according to Watson, is one that involves a dead leopard or an attack on a human. The second level is where leopards end up attacking and often killing livestock, dogs and causing economic damages.

Leopard sightings also tend to cause fear in humans – a phenomenon, said Watson, now on the rise, fuelled by media reports.

“Ten years ago, this wasn’t the case. Farmers used to say ‘we live with the leopards; that is how it is’. Now there is a changeover, maybe it’s the habitat matrix that’s changing, maybe it’s the younger generation not being used to living with wildlife. We like to ensure that coexistence remains and we don’t go into a conflict situation,” she said.

Leopards here, as previously pointed, out have no competitors. “Are humans, then, taking their role a lion or tiger would in other systems? If so, how are human actions contributing this? Are we part of the natural system here in Sri Lanka?” asked Watson.

Data set

Watson and her team able to analyse and verify data that had organically risen for 15 years.

A total of 180 incidents of which 90% had in the death of a leopard have been reported. Though the cause of death varies throughout the island, 50% of time it is listed as ‘unknown’. Poisoning, snaring, unconfirmed poisoning (some farmers will say they put poison on their calf, but they don’t actually know if the leopard ate the calf). There have also been cases were leopard skin was found, but there was no way of verifying whether they were killed for the skin or for something else.

In the Central Province, snaring is the biggest culprit, accounting for 67% of leopard deaths. There is no clear picture of what’s happening in the north central province as information from there has started flowing only recently, and quite slowly at that. In southern areas, said Watson, poisoning and also roadkill are among the biggest killers.

“Snares [in the central province] are not set for leopards. They’re set for wild boar or barking deer, but the leopard walks through [these snares]. People actually call this in. They don’t want the leopard dead. They do want something done about it, whereas in the south, they’re not likely to tell you [about poisoning], because they know what they’re doing is illegal,” she said.

Preventing escalation

“It’s important to educate people on other types of cat, so that there isn’t this huge fear that there is this monster leopard that’s going to come and eat them,” said Watson.

Anti-poaching regulation is also key. Incidental poaching is also reducing the prey base for leopards, which leads them to move to other areas. A rapid response team located at the site would be a crucial addition, she said, adding that providing necessary equipment to superintendents and villagers. Setting up an initiative like the Lion Guardian Programme could also help, she said.

A pilot project will soon kick off in selected estate areas that have had leopard incidents and where the management is keen to get this going, revealed Watson.

“Because this is a land matrix of mixed habitat, mixed ownership, there is no way one entity can do it alone. Everyone needs to come together. There is government land, protected land, private land, estate and company land. Often one doesn’t know about the other,” said Watson.

Pix by Chitral Jayatilake