Tuesday Feb 17, 2026

Tuesday Feb 17, 2026

Saturday, 12 December 2015 00:10 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Shiran Illanperuma

By Shiran Illanperuma

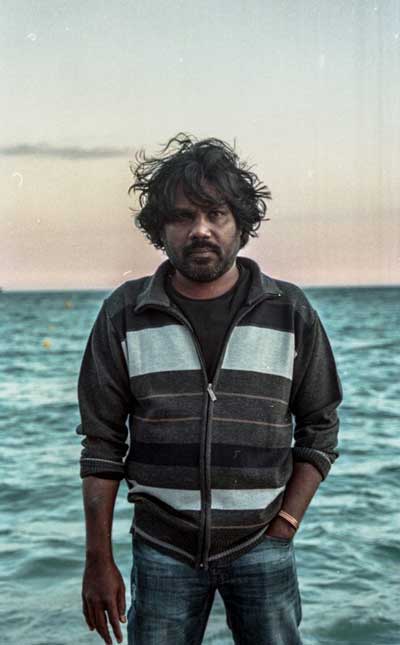

Shobasakthi is a man of many talents. A prolific writer and poet, he is well known in Tamil literary circles. As an actor, he made waves in the international scene with a searing semi-autobiographical turn as the titular character in Jacques Audiard’s Dheepan.

The film recently premiered in Sri Lanka at the International Film Festival Colombo and was well received by a packed audience at the Regal Theatre. As a refugee, Shobasakthi was unable to attend. The Daily FT reached out to him online to talk about the film and his experience of life in exile.

The following are excerpts from that interview:

Q: Dheepan premiered in Sri Lanka recently but you couldn’t attend. How do you feel about that?

A: I left Sri Lanka in 1990, it’s already been 22 years. I have presented Dheepan at several film festivals all over the world – Canada, Bosnia, Sweden, England and more. But I can’t come to my own mother country.

My status is refugee. My nationality is stateless – not Sri Lankan or French. I can’t come to Sri Lanka because of a legal problem. Secondly; I am afraid.

Q: Why are you afraid?

A: My friend, you know that I am a writer.

Last year one of my friends, a very famous poet called V. I. S. Jeyapalan visited Sri Lanka. He is 72 years old, lives in Norway and is very big in the Tamil community. He went to the Jaffna Press Club to give a speech. But then the Sri Lankan police arrested him and deported him.

Without freedom of speech, without the freedom to write, I don’t want to come to Sri Lanka. I live in France now, and there are not just Tamil refugees but also Sinhala journalists in exile.

Q: If you were able to come, what would you tell audiences?

A: I am just an actor in this film. And this is not really a political film. It is basically a love story. The film does mention the Sri Lankan war but we only had three scenes about it. It’s a love story about Sri Lankan refugees and how they struggle with a new life.

But for me it’s also a message to people who don’t have political rights. There is still land in the North and East occupied by the Sri Lankan military. Tamils are too small a group to make a significant political change only on their own. Sinhala progressive forces and politicians, artists and writers should struggle for equal rights for every citizen in Sri Lanka.

We fought for 30 years; it was one of the biggest armed struggles in the world. But it was a failure, because we didn’t have any support from Sinhala people.

Q: You’ve renounced the armed struggle and a separate state. Why?

A: I believe Tamil people – and all minority people – should struggle for their rights. I have always been part of that struggle. But now I am against armed struggle. The struggle should be political.

In the 1977 riots, I was 11 years old. I saw so many refugees coming from Colombo to Jaffna by the ship Lanka Rani. When I was 13, I saw the Jaffna Library being burned. I was 16 during the 1983 riots where 53 prisoners were killed in Welikada prison.

From 1980s the Sri Lankan military has been bombing our villages. The bomber doesn’t know who is a terrorist and who is a civilian. So they killed many civilians by air attacks.

This all happened around me, so when I was 16 years old, I joined the LTTE. At that time, they told us that we struggled for ‘Socialist Tamil Eelam’; that when we make a separate country there would be no class, caste or religion. But in 1986 the LTTE became the power centre. They banned all other movements, including the Communist Party and Dalit movement. They also attacked Muslim and Sinhalese civilians. That’s why I left them.

I believed in the armed struggle until the 1990s but now I think it won’t work. In Sri Lanka there were three armed struggles – twice by the JVP and one 30 year struggle by Tamils. What was the result? Nothing.

Hundreds of thousands died; thousands left the country and Tamil people lost everything.

Q: What was it like reliving your memories while shooting Dheepan?

A: I am always with my memories. I always write about these memories. All of my books – over 15 of them – are based on my memories from Sri Lanka.

Dheepan is just another chapter.

Q: One of the most powerful scenes in the film was when a drunken Dheepan sings in Tamil after confronting his old commander. How was that filmed?

A: After the confrontation with his old commander, Dheepan was meant to get drunk and dance. That was in the script. But on the day we started shooting they were playing Indian film music.

I found it very uncomfortable to act to that, so I asked Jacques Audiard if I could sing my own song. It’s a very famous LTTE song written by Puduvai Ratnadurai. I think he was the leader of LTTE cultural wing.

The song’s name roughly translates to “We are going to attack the enemy camp”. I thought it would fit the character and story better and Jacques was open to improvising these scenes with me.

Q: The film portrays England as a preferred location for refugees over France. Why?

A: My personal opinion is that France is better for refugees than England. But there are many reasons for Tamil refugees to prefer England.

Sri Lanka was a British colony so we have that cultural connection. The language is familiar. When Sri Lankan Tamils came to France everything about the culture and language felt very different. It’s the same story for many refugees who come from former British colonies. Also, people in France are more familiar with Arab and Black immigrants and refugees who have been there now for three or four generations. South Asians are still very new to the French and they don’t understand much about us even though there is a large group of Tamil Nadu people from Pondicherry settled here. The film was set in Calais, a border town between England and France. Until today there are many refugees waiting to cross the canal to England.

Shobasakthi in Dheepan

Q: The film has some mysterious shots of an elephant in the bushes. What does that symbolise to you?

A: Dheepan is a 40-year-old man from a guerrilla movement. He lost his family and his country. He is distraught.

When I think about my country, I remember palmyrah, elephants and the sea.

Q: How was Dheepan received by the Tamil diaspora?

A: The response was very good. In the West it was the first time that mainstream cinema talked about Sri Lankan Tamils. Sri Lankan refugees are a big community in Paris but Arabs and Black people have a longer history here. Their stories are covered in cinema and literature. The Sri Lankan issue is still very new to the French. So many French people still don’t know the difference between Sri Lanka, India and Pakistan.

Shobasakthi with co-star Kalieswari Srinivasan in Dheepan

Shobasakthi with co-star Kalieswari Srinivasan in Dheepan

Shobasakthi with co-star Claudine Vinasithamby in Dheepan

Shobasakthi with co-star Claudine Vinasithamby in Dheepan

Q: When people ask you where you are from, what do you say?

A: Of course, I say Sri Lanka! In the 1980s we used to say: “I come from Tamil Eelam!”

But I have forgotten that now.

Q: As an artist in many mediums, do you have a preferred medium?

A: I always like writing. Writing is my medium.

Honestly, I don’t have freedom in cinema as a scriptwriter. Cinema is the director’s medium. I can work as a scriptwriter and as an actor but that doesn’t make it my film. I write films for the director, with so many compromises. I’m very clear that cinema is a director’s medium.

But in a novel or short story, I don’t compromise. I am the decision maker, I am king.

Q: Do you watch Sri Lankan films?

A: Unfortunately I have seen only one Sinhala mainstream film. It’s called Palama Yata by Geetha Kumarasinghe. When I was in Sri Lanka I saw it in the cinema and was very impressed back then.

But I have seen many art films. Asoka Handagama is a very good friend of mine. Prasanna Vithanage is also my friend. I have seen all their movies. I have written about films like Puruhanda Kaluwara and Ini Avan.

In my opinion it’s not the Tamil diaspora or Tamil Nadu directors who have portrayed the war honestly in cinema. It’s been Sinhalese directors with films like August Sun, Death on Full Moon Day, Ini Avan and With You Without You who made the most honest portrayals.

In the Tamil artist community, there is a lot of respect and love for these Sinhala directors.

Q: What do you hope for Sri Lankan Tamil art and culture post-war?

A: Before the war, we didn’t have much cinema. We had one good film called Ponmani – a Tamil film by Sinhala director Dharmasena Pathiraja.

But back in the 1970s we had very powerful literature. The communist movement helped nurture progressive writers. When the war started, these writers had to close their mouths. Tamil militant movements censored and banned any alternative writers and opinion. From 1986 to 2009 there was only one voice – the pro LTTE voice. That was propaganda, not art.

But there were so many writers in exile. In Europe, Canada and Australia we published so many magazines of Tamil literature. From Europe I think there are over a hundred Tamil publications in the 1990s.

After the war, now so many young talented writers have revived literature. I know more than ten youngsters from the North and East who write very well.

Q: How has your life changed after Dheepan?

A: The only difference is that a lot of media people come after me now. A couple of people approach me almost every day. And they normally ask more about politics than my art.

Because of my platform I try to educate people about Sri Lankan Tamil problems and refugee problems in general. With the refugee crisis in Europe I always try to shout for our cause and say that refugees should be welcome.