Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Saturday, 29 October 2016 00:08 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Madushka Balasuriya

“Sri Lanka is one of the best places in the world for shipwreck diving and for whale and dolphin watching. That’s an unbeatable combination,” enthuses Independent Marine Researcher Howard Martenstyn.

Martenstyn is addressing the recently-concluded Colombo International Maritime Conference. His presentation centres round Sri Lanka’s untapped potential as a go-to marine life tourism destination, not only in the region but globally. The eight-minute slot he is  allocated seems terribly insufficient to adequately cover the topic at hand, and while undeniably drawing the room’s attention to Sri Lanka’s rich biodiversity, he primarily succeeds in piquing my curiosity. Needing to know more, I arrange to meet him at his home in Mirihana a little over a week later.

allocated seems terribly insufficient to adequately cover the topic at hand, and while undeniably drawing the room’s attention to Sri Lanka’s rich biodiversity, he primarily succeeds in piquing my curiosity. Needing to know more, I arrange to meet him at his home in Mirihana a little over a week later.

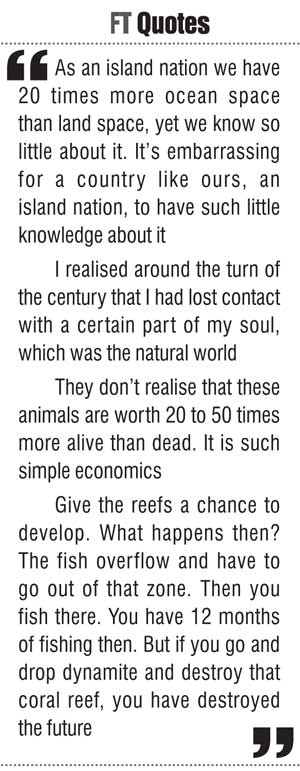

“As an island nation we have 20 times more ocean space than land space, yet we know so little about it. It’s embarrassing for a country like ours, an island nation, to have such little knowledge about it. This is why I moved my focus on to marine life, because really that’s where we need to spend time,” he says, adding that settling on his eventual vocation was just a means to rediscovering his passion in life.

“My passion comes from my childhood, from my family. They say I was born into a family with flippers on. It started with my father, a respected pioneer in the maritime business who actually registered his company on my birthday in 1953.”

Howard’s father passed away when he was 10, yet his love affair with the ocean was just beginning. His brother Cedric (“virtually a legend when it came to marine life water sports and naval life,” gushes Howard), who died during the war, played a “huge influence” in this aspect, he reveals, offering up an oft-used anecdote of how his elder sibling had thrown him into the ocean at the age of 12 despite him not knowing how to swim. Howard, needless to say, was a quick study and the ocean forever stole a place in his heart, but his passion would have to take a backseat for several years.

After finishing his schooling at S. Thomas’ College, by the age of 20 Howard had begun the process of acquiring a Bachelor’s degree in Control Engineering from the University of Sussex. This was followed by a Masters in Computer Engineering from the University of Kent, which would come in handy later when designing the Sri Lanka Amazing Maritime (slam.lk) website. Howard ended up spending a total of 10 years in the UK, and a further 23 in Canada. Yet despite all these achievements, it was only post-retirement Howard says he found his true calling.

“I realised around the turn of the century that I had lost contact with a certain part of my soul, which was the natural world, which came back to me on a trip Africa. From the day I left Sri Lanka I always said I would come and retire here, so when I did come back I was very much into the natural world, in the jungles and at sea. It was then that I realised how little we knew about the sea and how easy it was to make discoveries.”

Out of the Blue

What began as a hobby soon turned into intensive research. By 2011 Dr. Hiran Jayawardene, the Founder/Chairman of NARA (National Aquatic Resources Research and Development Agency), had taken notice of Howard’s research, and invited him to make a presentation at an international conference.

“I of course had nothing to compare my work with but I went and presented anyway. Five people came and shook my hand  afterwards. It was then that I realised that I had something special. What was borne out of that conference was the idea of the book. I knew I needed to share what I had learned.”

afterwards. It was then that I realised that I had something special. What was borne out of that conference was the idea of the book. I knew I needed to share what I had learned.”

Howard half jokes that the research for his book was tougher than any dissertation, but much of the leg work was already done by the time he had decided to write it. “I have my own private books, for my research which I create. But the final draft I needed to rewrite it at least 10 times after that, because you have to have your target audience and so on.”

In 2013 ‘Out of the Blue: A Guide to the Marine Mammals of Sri Lanka, Southern India and the Maldives’ was published with special focus on Sri Lankan marine life and its adjacent oceans. Howard’s findings were revelatory. Sri Lanka it turns out was home to some of the most diverse marine life in the world, and the at-the-time relatively unknown independent researcher Howard Martenstyn was privy to some incredible sightings.

“Nobody knew me, I wasn’t interrupted, I didn’t have presentations to do. It was my passion. I was just following my passion and living my dream.

“For the work I did I could get up anywhere between 12:30 and 4 in the morning. I got some great opportunities because I was able to get in my car and go on a moment’s notice, on a phone call,” he adds, being sure to thank his wife for making this level of flexibility possible.

“As a result I got some fantastic sighting events. From flamingos in Bundala to Fraser’s dolphins in Kalpitiya – from the end to the head of the pod it was 1.1 nautical miles – I couldn’t even count how many there were. I had no idea! When we saw 100+ sperm whales in Kalpitiya, that was on a phone call too.”

Howard spent most of his time conducting research in Kalpitiya, where his younger brother Dallas runs a hotel, thereby ensuring his costs were kept low and his time flexible.

“I was very fortunate because I based most of my research work in Kalpitiya; I had my own boat there, I had my boatman, my brother has a hotel there. So my costs were minimal – I’m very thankful to my brother for that.

“On the other hand in Trinco I paid by the hour. So you know from the point of view of spending time with the animals, the best was Kalpitiya. My boatman was just as passionate as I was; when we left in the morning we didn’t know what time we would come back. Whether we had food or water or whatever, that was never an issue for us. We would go and enjoy our time. That was just a privilege to be able to do something like that.”

Howard’s research has thus far seen the documentation of 27 species of marine mammal in total, most notably blue whales and orcas, in Sri Lankan waters. Sri Lanka is also said to play host to over 100 species of sharks and rays, with some such as whale sharks and giant manta rays having “tremendous touristic value”.

In addition to this, Sri Lanka has an abundance of coral reefs around the island, with around 180 coral species recorded. Add to this Sri Lanka’s extraordinary collection of shipwrecks and the island nation transforms into the epitome of a tourist destination.

The shipwrecks in particular offer up some unique opportunities, explains Howard. “These wrecks usually sit on a sandy seabed with nothing around it, and all your fish are concentrated there. So you get all these shoals, and occasionally you get a predator fish that comes in for an attack.

“This is unlike a coral reef, where things are spread out a lot more and they have places to go and hide. Lion fish for example – which you only see in the evenings on a coral reef – you can see them anytime near a shipwreck.”

Lack of awareness

Sri Lanka has an estimated 200 shipwrecks around its coasts, with a lot of WWII-type shipwrecks on the Batticaloa side, more archaeological ones around Galle, and newer ones near Colombo. However, according to Howard, people haven’t yet realised their importance. A cursory glance at the Ministry of Tourism website offers not even a trace of information on Sri Lanka’s rich marine life, while World Tourism Day came and went last month without even a mention of marine tourism.

Yet despite this seemingly inexcusable lack of Government initiative, Howard is definitely more of the glass half-full persuasion, always looking at ways he can improve his situation even when outside assistance isn’t forthcoming.

“Any help that you can get is fantastic, but if you sit at home and cry because you’re not getting help, then you’re not going to move forward. I always say push ahead, you don’t have to wait for somebody else, you do what you can with what you have. And you must push ahead and progress.”

Howard also notes there more independent researchers now than when he started, though he feels a cultural shift needs to take place for information to be more widely available.

“Before you could count them on one hand, now I can go beyond my two hands. You see in Sri Lanka everybody is very independent in their research, so their information is quite private. From my perspective, I know to share, and I share everything that I have. I’m happy to continue on the path that I’m going along.”

This though means he takes a tough stance on a public that can sometimes simultaneously look the other way when it comes to environmental protection while also bemoaning the lack of law enforcement when it comes to the same.

“What about you? You got on that boat, you went out there, you watched it happen, what did you do about it?” he asks rhetorically, drawing on an example of tour operators sometimes dropping anchor on coral reefs. “In Trincomalee I’ve seen boats right along the bay, and this one operator he would actually go out there and instead of using the anchor buoy, he’d drop the anchor straight onto the coral reef.

“So don’t come back and say there’s no enforcement, you’re the enforcer,” he adds. “Don’t get on Facebook and start moaning about it; you were there, you have to be responsible. You can write on TripAdvisor, you can complain to the tour operator. And things get done that way but people don’t, they don’t take responsibility. This is where I’m in disagreement that we leave everything up to enforcers. No, no, no.”

Simple solutions

At the same time he acknowledges there are some “simple things” the Government could be doing to improve the situation. One is that he would like to see more fisherman converted to tour operators, which he says would boost income.

“A little less fishing and more tourism. Now tourism isn’t perfect. But with tourism you can see, for example, if we move fisherman over you’re going to conserve your ocean more, that’s number one. Number two, their income; they don’t realise that these animals are worth 20 to 50 times more alive than dead. It is such simple economics.”

He uses the example of Mirissa as a model built on fisherman moving to tour operators, but acknowledges that it is still not a perfect solution.

“It’s not just the vessels, it’s also the entire town [Mirissa] that has benefited. It has transformed. Why? They’ve stopped killing fish and they’re taking tourists out to sea.

“But there are drawbacks. We have this herding mentality, they also have to learn customer service. A fisherman who sees blood everyday has to have a different mentality. You have to go through a rehabilitation program. But there isn’t one. Fisherman are used to viewing animals as a source of food and nothing else.”

Going hand in hand with this is education for future generations, which Howard believes is essential in protecting all forms of wildlife in the country, something he hopes his work will eventually help achieve.

“I understand that there’s no immediate benefit to the country from my work, but I treat my work as legacy work. That one day it is going to be useful to somebody. That is why it is very important to educate our children. They are going to be the change agents of the future. So educating our children will see us reap benefits.

“Unfortunately you can’t change an oil tanker on a dime, you can’t change conservation practices the same way. Therefore we know it is a progressive activity that has to take place, but with people who are educated on the subject.”

In the meantime, Howard hopes for an increase in the amount of resources being dedicated to marine life conservation in the country.

“For one NARA needs to be developed. The second thing is, the Wildlife Ministry has appointed a marine unit, but when you have more sea area than land area you must have more people in your marine unit than in your land unit. For me, they actually have to start a complete marine unit which is separate from the land.

“What they’re trying to do now is occasionally borrow an odd person from the land unit – someone who most likely has no interest in the sea – so what we really need in the Wildlife Department is an independent and completely different unit, with a director general overseeing each.”

With this he feels the Government can then put in place and enforce a 200-300 metre no-fish zone for all coral reefs in Sri Lanka. This, along with banning the dropping of anchors at a coral reef, will help replenish depleting stocks of fish, he explains.

“You put in a mooring buoy, what does it cost you to put one in at any coral reef that you want to use? You don’t need the Government to do that, the tour operator must do that. You want to go use that reef, put in the mooring buoy.

“This will give the reefs a chance to develop. What happens then? The fish overflow and have to go out of that zone. Then you fish there. You have 12 months of fishing then. But if you go and drop dynamite and destroy that coral reef, you have destroyed the future.”

Neighbourhood examples

Overall Howard’s calls to action aren’t revolutionary, in fact his ideas aren’t particularly original. He is simply urging the Government to take heed of the work being done by its neighbours, some of whom have much less but are extracting considerably more from their marine life resources.

The waters surrounding Maldives, for example, have been designated as a complete shark sanctuary, in India whale sharks are a protected species, while the greatest example may be Palau.

A fraction of Sri Lanka’s size, Palau holds far more than seems possible in the 170 square miles it covers, supporting more than 400 coral species and nearly 1,300 varieties of reef fish. The Government of Palau has been the key force behind their efforts to effectively conserve at least 30% of their near-shore marine resources and 20% of their terrestrial resources by 2020. Palau is also a shark sanctuary, with its Government and people both understanding how critical sharks are to the ecosystem; the top predators in the ocean help maintain the health of the populations of smaller fish.

Sri Lankan fisherman and tour operators by comparison fail to grasp that overexploiting marine life will only provide short-term returns, with devastating consequences in the long run. This destructive process can only be halted if all relevant stakeholders, the public and the Government come together in raising and creating a culture of awareness and empathy towards Sri Lanka’s extraordinary marine life.

To quote Howard: “The oceans don’t need us, we need the oceans.”

Pix by Sameera Wijesinghe