Sunday Feb 15, 2026

Sunday Feb 15, 2026

Saturday, 26 September 2015 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By D.C. Ranatunga

Sri Lanka continues to be synonymous with tea. In the recent news feature in the UK Sunday Times introducing Sri Lanka as ‘Our Destination of the Year’, the picture used was a smiling tea plucker in the midst of a tea plantation.

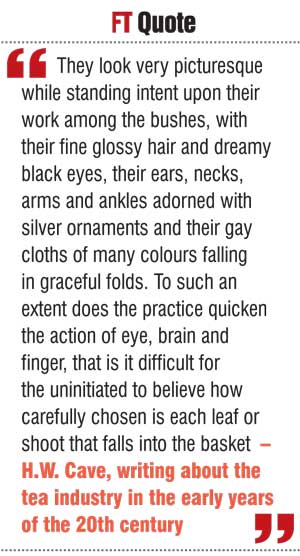

We are used to seeing that scene from our young days but it looks as if no one gets tired of it. And the plucker’s work kit has not changed either. The cloth covering her head and falling down, the basket suspended by a rope form the head, the thick cloth (in early days a gunny bag) round her waist still form part of her kit. So is her style of plucking when she casts the leaves over the shoulder.

“They look very picturesque while standing intent upon their work among the bushes, with their fine glossy hair and dreamy black eyes, their ears, necks, arms and ankles adorned with silver ornaments and their gay cloths of many colours falling in graceful folds. To such an extent does the practice quicken the action of eye, brain and finger, that is it difficult for the uninitiated to believe how carefully chosen is each leaf or shoot that falls into the basket,” describes H.W. Cave, writing about the tea industry in the early years of the 20th century.

Identifying plucking as a most important part of the tea planter’s business, he says that it requires careful teaching and constant supervision. “Only the young and succulent leaves can be used in the manufacture, and the younger the leaf, the finer the quality of the tea, so that if a specifically delicate quality is desired, only the bud and two extreme leaves of each shoot will be taken; whereas if a large quantity is wanted, as many as four leaves will be plucked from the top of the shoot downwards, but with the result of a proportionately poorer quality of the manufactured article, There are many other points in the art of tea plucking that require care and judgement, as, for instance, the eye or bud of the axil of the leaf plucked must be left uninjured on the branch, and where special grades of tea are required the selection of particular leaves is of the utmost importance.”

Leading plantation crop

From our school days we were taught about the three main plantation crops – tea, rubber and coconut – which brought foreign exchange to the country. Hardly anything else was talked about as our foreign exchange earners. After over a century tea is still the leading plantation crop.

In ‘The Geography of Tea’, Maxwell Fernando traces the first reference to tea in Sri Lanka to 1782 when Johann Christian Wolf had reported that “Tea and some other sorts of elegant aromatics are not to be found here (Ceylon). Some trials had been made to raise these but without success.” That was the time that only Chinese tea was known.

Tea pluckers in the early days

James Cordiner, author of ‘A Description of Ceylon’ has mentioned that around 1805 tea plants were growing wild near Trincomalee and that the soldiers had dried the leaves, boiled them and drank in preference to coffee. This is corroborated by another writer, Captain Robert Percival of the 18th Royal Irish Regiment, who wrote that tea plant “grows spontaneously in the neighbourhood of Trincomalee and other northern parts of Ceylon.” He also talks about the soldiers frequently using it. “They cut the branches and twigs and hang them in the sun to dry. They then took off the leaves and put them into a vessel or kettle to boil to extract the juice, which have all the properties of that of the China tea leaf. Several of my friends have assured me the tea was looked upon as far from being bad, considering the little preparation that it underwent. Many preferred this form of tea to coffee,” he wrote.

“A thorough success”

Records indicate that even when coffee dominated the scene, tea and cinchona were tried out as subsidiary crops along with cinnamon and other spices for which the country was well known. Tea had been brought from Assam in India first in December 1839 and then in 1842. Some of the plants from the second lot had been given to Oliphant Estate in Nuwara Eliya. Another lot of 270 plants propagated rom Assam seeds had been planted at Hakgala Gardens in 1866. Dr. G.H.K. Thwaites, Superintendent of the Peradeniya Gardens who opened the Hakgala Gardens in 1861 reported that it was “a thorough success”.

Meanwhile, a stock of Chinese seed had been tested in a nursery on Barra Estate, Rakwana in 1864. In 1872 tea manufactured from this plot had been valued at 2 shillings 4 pence per pound which led to more serious cultivation on that estate.

A commercial success

With planters trying out the new crop, by 1875 tea was accepted as a commercial success. Referring to the tea crop at the Rothschild Estate, Ramboda, Sir Emerson Tenant wrote: “On this fine estate, an attempt has been made to grow tea. The plants thrived surprisingly well and when I saw them they were covered with bloom. Unfortunately, the experiment has hitherto been defeated by the impossibility of finding skilled labour to dry and manipulate the leaves. Should it ever be thought expedient to cultivate tea in addition to coffee in Ceylon, the adoption of the soil and the climate has thus been established, and it only remains to introduce artisans from China to conduct subsequent process.”

”A small tree growing from the coast to Dimbula,” is how Dr Henry Triman, Director of Peradeniya Gardens (1880-86) described the tea plant. “Its leaves were found to be strongly serrated.”

James Taylor

Credit is given to a pioneer coffee planter, James Taylor for the success of tea. Having planted tea successfully at his Loolecondera Estate at Hewaheta he confirmed that tea could be grown as an alternate plantation crop to coffee.

“Loolecondera by 1888 had become a showpiece with its visual impact, and Taylor was able to unfold to all future tea planters the potential available in tea. Many were the compliments paid to him,” writes Maxwell Fernando. “The most interesting factor about the ‘original tea plot’ planted in 1867, was that the first dose of fertiliser in the form of caster cake was only administered in 1885, but production figures indicated that the bushes were growing vigorously and the yields had been maintained around 475 pounds of made tea per acre.” By 1901 the figure had gone up to 566 pounds.

The collapse of coffee paved the way for tea to establish itself as the main plantation crop. Cinchona and cocoa were also tried out but tea was the success story.

The need for labour was solved by bringing in Indians. The government improved transport facilities particularly by extending the railway to the tea grown areas.

The plucker’s routine

To continue Cave’s narrative on the plucker’s routine, he says: “It’s now about ten o’clock, and the baskets of the most dexterous pluckers should be nearly full. The superintendent therefore returns to them and notes against their names the weight of leaf plucked by each, after which the baskets are emptied and the leaf conveyed to the factory. This operation is repeated two or three times during the course of the day. At four o’clock the pluckers cease work and carry off their baskets to the factory, where they sort over the leaf upon mats spread on the ground and cast away any coarse leaf that may have been accidentally plucked.

“The number of pounds plucked by each cooly is again entered in the check roll against his or her name, and then the sum of each plucker’s effort passes before the eye of the superintendent before the coolies are dismissed; and woe beside him or her, who has not a goodly weight accounted for. Laziness thus detected brings a fine of half pay and in many cases a taste of the cangany’s stick.”

Sorting out tea leaves – Pix by H.W. Cave