Wednesday Feb 18, 2026

Wednesday Feb 18, 2026

Saturday, 7 January 2017 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

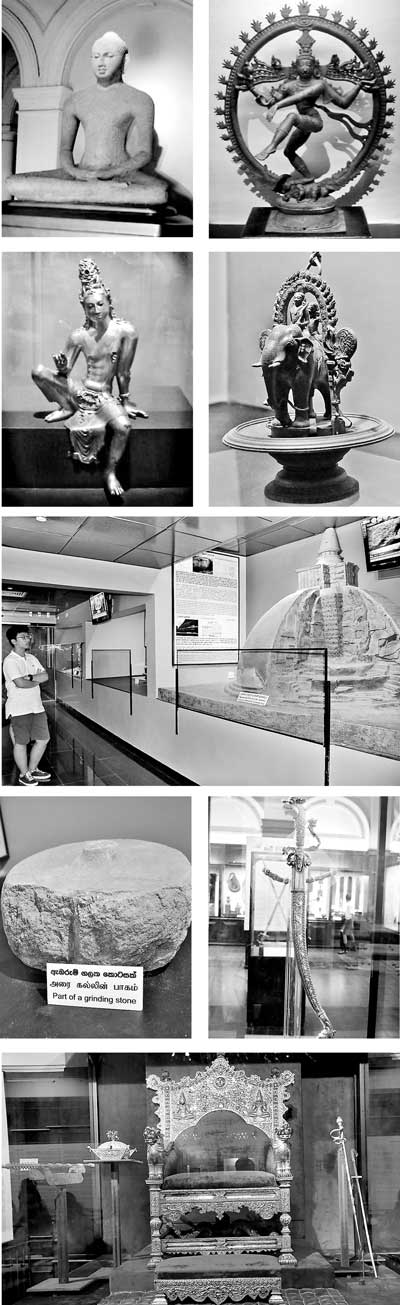

For outstation school trips to Colombo the ‘Katu ge’ and ‘Ho gaana pokuna’ are invariably in the itinerary. ‘Katu ge’ is the easier way of identifying the ‘Kautukagaaraya’ – the Museum.

Translated as ‘Skeleton House’, it came to be known as the ‘Katu ge’ because of the skeleton of a huge whale hung on the ceiling of the then National Science wing in the museum. (Today there is a separate National Museum of Natural History)

What was started as the Colombo Museum is today the National Museum, Colombo.

In two days the National Museum enters its 140th year. The museum was established on 1 January 1877 when Sir William Henry Gregory (1872-77) was Governor in the colonial administration. He was deeply interested in the arts and fully supported the Royal Asiatic Society, Colombo branch when they proposed the establishment of a museum.

In his first address to the Legislative Council in 1872 he proposed the construction of a museum. “I propose in connection with this museum to obtain reproductions of the inscriptions throughout the island by means of photography, casts and hand copying. These inscriptions, varying in character and dialect, will be of deep interest to the philologist and throw light on the ancient usages, religious customs and early history of Ceylon,” he said.

However, at that stage the Legislative Council did not support the Governor and approval was delayed. Somehow Governor Gregory managed to get approval within the year and the Chief Government Architect, James G. Smithers was requested to design the museum. The building was completed in 1876 and the Colombo Museum was formally opened on 1 January 1877.

The statue of Governor Gregory in front of the museum stands as a memento for the role played by him.

He was considered one of the ablest and most enlightened men to hold the office of governor in what was then the Crown Colony of Ceylon in the British Empire. After assuming duties as governor he made an extensive tour of the country. He later formed the desolate and abandoned tank region of Nuwarakalawiya into a separate North Central Province (NCP) and proclaimed the city of Anuradhapura as its capital. He appointed Frederick Dickson, an able and experienced official to administer the province. Governor Gregory started restoring the tanks built by ancient kings and within the first year work was going on at some 900 tanks. He was greatly supported by Dickson in this task.

“Crops were obtained where they had failed for years. The revenue rose immensely, sickness gradually declined, an eminently listless and lazy population being compelled to work resumed habits of industry,” he wrote.

The name of Arasi Marikar Wapchie Marikar (1829-1925), popularly referred to as Wapchi Marikar Bass, is mentioned as the builder of the Museum. He is also credited with the construction of well-known government buildings of the past including the General Post Office (GPO), Colombo Customs, Old Town Hall (Pettah), Galle Face Hotel and the Clock Tower in Fort. He is identified as a descendant of the Sheiq Fareed family who arrived in Ceylon in 1060 AC).

According to Wikipedia, when the completed building was opened by Governor Gregory among the large crowd present were many Muslims. At the end of the ceremony, the governor had asked Wapchi Marikar what honour he wished to have for his dedication. Marikar requested that the museum be closed on Fridays, the Muslim sabbath and this request was granted and maintained for a long time until it was decided to close only on public holidays.

When the carpenter S.M. Perera who was responsible for the woodwork of the Museum was asked how he preferred to be honoured, he had requested a local rank which was awarded.

There had been 11 directors heading the Museum over the 140-year period. Four of them – Dr. Amyrald Haly (1877-1901), Dr. Arthur Willey (1902-09), Dr. Joseph Pearson (1910-33) and A.H.M. Malpas (1933-39) – were Englishmen.

Dr. P.E.P. Deraniyagala (1939-63) was the first Sri Lankan to hold the post of director. Three years after his appointment the Colombo Museum gained the status of a National Museum under a special Act – 1942 Act No 31. Dr. Deraniyagala opened museums in Jaffna, Kandy and Ratnapura and now the number of branches has increased to nine.

His successors were N.B. Seneviratne (1963-65), Dr. P.H.D.H. de Silva (1965-81), Dr. Thelma Gunawardena (1982-94), Sirinimal Lakdusinghe (1994-99), Yasantha Mapatuna (1999-2001) and Dr. Nanda Wickremasinghe (2001 onwards).

Over the years the museum has expanded and new wings have been added.

In recent years HSBC has played a prominent role in upgrading the facilities in the National Museum.

‘A Guide to the National Museum’ (2012) states that the Museum is complete with divisions of Ethnology, Anthropology, Entomology, Zoology (Taxidermy), Botany, Geology, Artefacts conservation, Education and Publication, Exhibition Design unit, and Photography “enjoying the pride of being a leading museum in Asia”. The library with very rare manuscripts in recognised as a leading library in Asia.

Chief Architect Smithers’ designs encompassed a remarkable range of styles, which varied in complexity and scale from residential bungalows to larger civic buildings. The Colombo Museum complex was his most outstanding work and stands as one of the finest achievements in 19th century colonial architecture in Southeast Asia.

The two-floor building is ingeniously designed around several courtyards which provide through-ventilation, a necessity in a tropical climate particularly before the advent of electrical or mechanically-aided ventilation.

The elegant structure is effectively enclosed by an arcaded verandah protecting the building against harsh monsoon rains and glare. The verandahs not only provide a functional and practical space, but also aesthetically enhance the building’s appearance.

The local feature is the portico (porte-cochere) from which he building is approached by a flight of steps leading into the entrance lobby lined with columns. Beyond the lobby is the grand staircase leading to the upper-floor exhibition halls.

The shallow-pitched roof (originally of tiles, but later covered in corrugated asbestos) is effectively concealed by a parapet balustrade heightened by pediments over the entrances. The interior, including the floor and ceiling, is exquisitely finished and fitted with local wood.

– ‘Images of British Ceylon,’ Ismeth Raheem and Percy Colin Thome