Wednesday Feb 25, 2026

Wednesday Feb 25, 2026

Saturday, 10 June 2017 00:28 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

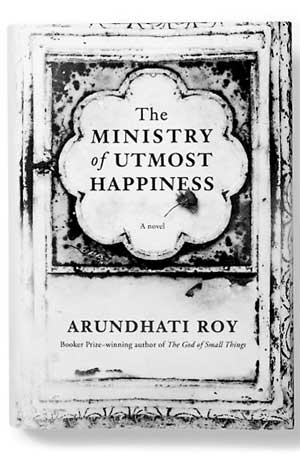

TIME IDEAS: Indian author Arundhati Roy attained instant literary fame with her 1997 debut novel, ‘The God of Small Things,’ which won the Man Booker Prize, topped international best-seller lists and became required reading for high school and college students, cementing its status as a modern classic. Roy has published more than a dozen nonfiction books in the 20 years since but  hasn’t produced another novel. Until now.

hasn’t produced another novel. Until now.

Like its predecessor, ‘The Ministry of Utmost Happiness’ is a complex, nonlinear narrative that blends the personal and political. But unlike ‘The God of Small Things,’ which focused on a pair of twins whose tragedy was familial, this is a novel of conflict on a grand scale.

Although the plot spans 50 years, leading up to the present day, and encompasses a vast cast, it orbits around two women in particular. The first is Anjum, an Old Delhi hijra (a word used in Urdu and other languages to describe trans women and other gender identities) who spends the first part of her adulthood living in a hijra boarding-house before setting up camp solo, in a graveyard. She and her fellow hijras live separately from what they see as the real world.

As one hijra puts it, “normal people” get upset about “price-rise, children’s school-admissions, husbands’ beatings, wives’ cheatings, Hindu-Muslim riots, Indo-Pak war—outside things that settle down eventually. But for us the price-rise and school-admissions and beating-husbands and cheating-wives are all inside us. The riot is inside us. The war is inside us. Indo-Pak is inside us. It will never settle down.”

The other pivotal woman in this novel is Tilo, a nonconformist architect with a personality like smoke quiet, diffuse, bewitching. Thanks to a sometimes-requited romance with a Kashmiri insurgent, she becomes an observer of, and even a participant in, the conflict there. “I would like to write one of those sophisticated stories in which even though nothing much happens there’s lots to write about,” she writes in her notebook. “That can’t be done in Kashmir. It’s not sophisticated, what happens here. There’s too much blood for good literature.”

There may be terrible bloodshed in ‘The Ministry of Utmost Happiness,’ but it is undeniably good literature. Roy’s rich and knowing narration wings across the landscape, traversing caste, religion and gender divides. She acerbically captures the cruel ironies of a city like Delhi, where dead paupers lie “in air-conditioned splendour” in the morgue, despite never having “experienced anything of the kind while they were alive”.

She has a keen sympathy for women in dangerous spaces, whose bodies are used as shields, sacrifices and good-luck charms. But women can use their bodies as weapons too, as when Anjum wins a public argument with a politician by going into a courtesan’s dance, swirling her hips and clapping her hands—“aggressive sexuality aimed at humiliating” the bashful man.

Victimised women can also form healing bonds among themselves. After the trauma of Kashmir, Tilo settles into Anjum’s graveyard compound, now a shantytown for various lovable outcasts.

At the heart of the novel is an interrogation of sectarian violence, why it persists and what feeds it. Government complicity and military malfeasance play a role, yes. But as one character explains, it boils down to this: people “aren’t very good at other people’s pain”.

Arriving as it does at a time of geopolitical uncertainty, Roy’s novel will be the unmissable literary read of the summer. With its insights into human nature, its memorable characters and its luscious prose, ‘The Ministry of Utmost Happiness’ is well worth the 20-year wait.