Friday Feb 20, 2026

Friday Feb 20, 2026

Saturday, 5 August 2017 00:02 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Explore Vietnamese caves, remote Laotian mountains and a rustic Sri Lankan getaway

Today’s Asian traveller is increasingly venturing off the beaten path and seeking out more immersive and adventure-packed experiences. Here Nikkei Asian Review’s Marwaan Macan-Markar and Yukako Ono look at three destinations that will take you out of the tour bus and into a world of exploration

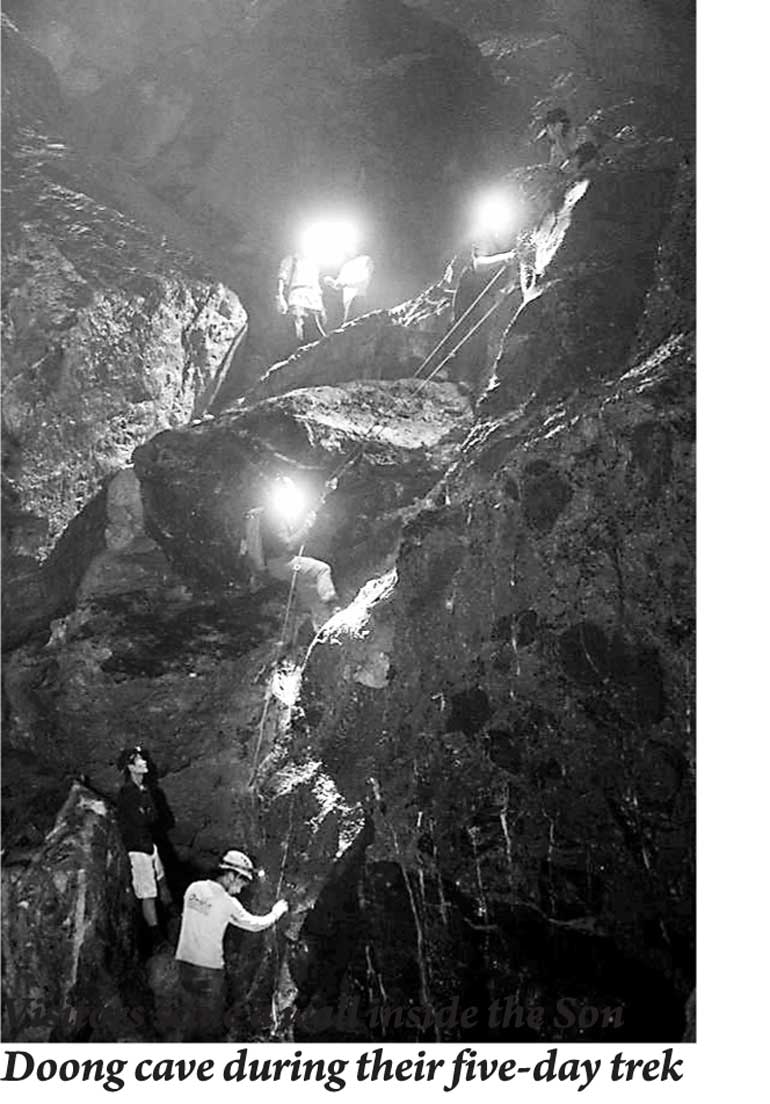

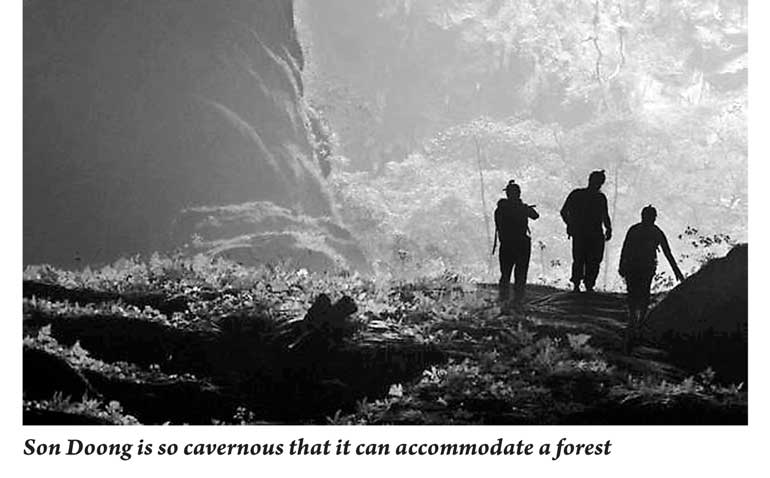

UNDERGROUND ALLURE

Vietnam’s stunning Son Doong cave has mass appeal but limited access

Vietnam’s stunning Son Doong cave has mass appeal but limited access

Kim Thi, a freelancer who lives in Ho Chi Minh City, had exploration on her mind when she emailed Oxalis Adventure Tours in February last year. She was set on visiting Son Doong, the largest cave in the world, and wanted to know when the earliest opening was. Oxalis, the only company licensed to operate tours there, put Thi on a waiting list and told her to stand by for its call.

A week later, she got word that a foreigner had canceled their trip and that a slot was available the following month. With less than a month to prepare, Thi scrambled to whip herself into better shape and buy all the necessary gear.

Son Doong is located in Phong Nha-Ke Bang National Park, a UNESCO World Heritage site in the northern province of Quang Binh, some 500km south of Hanoi. The cave attracted international attention in 2015 when local developers proposed building a cable car there to shuttle in a thousand visitors per hour.

The plan sparked outrage in the media and on the internet. Video footage of the cave went viral on Facebook, accompanied by calls from environmentalists for sustainable tourism. The plan was put on hold, but all the attention caused even more people to line up for tours.

That included Thi, who was among the approximately 100 Vietnamese who paid $3,000 for the trip last year. She said she did it because she loves adventure and wanted to see for herself what all the fuss was about.

Son Doong, one of the park’s 150 natural grottos, is 9km long, over 200 meters wide at its broadest point and 150 meters high. It shelters underground rivers and waterfalls, chambers, fossils and some of the largest stalagmites and stalactites in the world.

“It’s hard to describe the beauty,” Thi said of the cave. “You have to see it for yourself, but it was truly a once-in-a-lifetime experience and totally worth the price. I want my children, and my children’s children, to experience what I did.”

The five-day expedition includes a trek through Son Doong’s underground forest, a visit to an ethnic minority village and an exploration of the nearby Hang En cave. The tours were created with input on safety and sustainability from British cave experts.

Only up to 10 visitors are allowed in each group, though they are escorted by a team of 30 porters, cave experts, Vietnamese- and English-speaking guides and park rangers.

Some 230 people, mostly Westerners, were allowed to visit the cave in 2014. The cap has since been raised to 500, and special tours exclusively for photographers have also been created.

This year, Oxalis introduced a four-day trip on a trial basis. The shorter tours are expected to allow another 500 visitors per year without hurting the ecosystem.

IRRESISTIBLE AUTHENTICITY

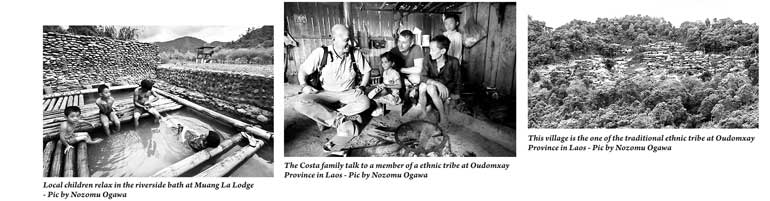

Unspoiled nature and ethnic tribes draw tourists to Muang La, Laos

Unspoiled nature and ethnic tribes draw tourists to Muang La, Laos

It could be the cautious eyes of a hill tribe granny, the beaming smiles of a group of schoolgirls, or a friendly invitation to an early evening family drink and a bite of local insect food. Whatever the encounter, Muang La, an off-the-radar district nestled in the lush mountainsides of northern Laos’ Oudomxay, is steadily drawing tourists seeking a peek at “authentic” local lives.

Jean-Alexis Costa, a 35-year-old Frenchman, is one such explorer. A hotelier residing in the Caribbean, he and his family came for a tour into the mountains that are home to more than 40 of the total 70 or so ethnic tribes in the country.

Especially for his daughter, the bare earth floor of a Hmong tribe bamboo house, the dark-skinned Sino-Tibetan Akha tribeswomen wearing colourful costumes and children running around half-naked were eye-opening.

The five-year-old admitted that she would prefer to live and work in Paris when she grows up. Nevertheless, her father was glad she had the experience. “We wanted her to see the world outside her daily life,” he said.

The Muang La district was practically untouched by Western influences until Muang La Lodge, the first and still the only accommodation targeting foreigners, was built in 2008. Run by a French-Lao couple, the resort is surprisingly luxurious despite its remote setting – it has air conditioning and Wi-Fi, and offers a sophisticated menu of French-Lao fusion cuisine.

The 10-room lodge has largely involved the local community over the years. It hires directly and indirectly about 60 residents, pays taxes and buys food locally. In addition, it turned a muddy hot spring into a public bath for the people who would otherwise bathe in the river, which can get rather cold in the winter.

Having tourists around has helped the community in other ways, said Xay, a 38-year-old Khmu tribesman whose village is sometimes visited by the tours organised by the resort. Not only do they get a share of the tour fares, but some tourists “donate” goods such as pens and books.

“The villages have developed and we could say have become less authentic compared to 10 years ago,” said Jean-Paul Duverge, managing director of Muang La Lodge. But he added that the place is still way off the beaten track compared to tourist-packed cities like Luang Prabang. We have to understand, he said. “When you have been living in bamboo houses you would want a concrete house. The people deserve it.”

(Marwaan Macan-Markar is Nikkei’s Asia regional correspondent and Yukako Ono is a Nikkei staff writer.)

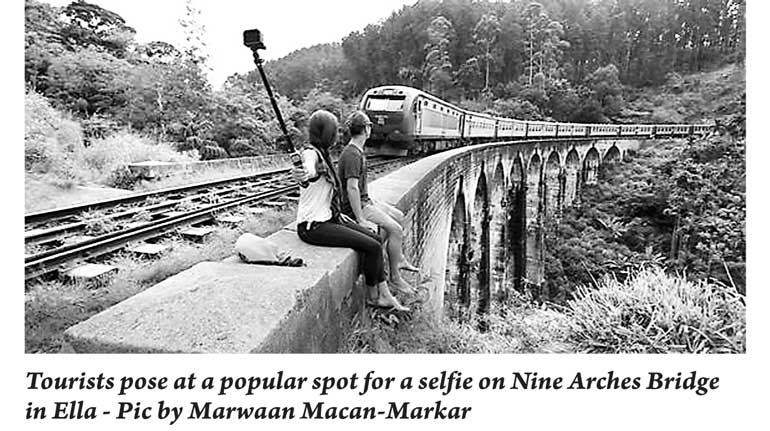

BEATING A NEW PATH

Social media puts a Sri Lankan mountain town on the tourism map

Social media puts a Sri Lankan mountain town on the tourism map

Standing on his right leg with his left foot tucked against his knee, a young Kazakh strikes a yoga pose in the morning light in a garden in Ella, a small, quiet town perched high among the tea plantations of southern Sri Lanka. His girlfriend takes a quick picture with the spectacular backdrop of the “Ella Gap” – a lush valley stretching down to the plains below.

They were drawn to the town for its “nature and walks,” said Rishat Kerimbay, 27, pausing from his yoga routine while his girlfriend takes a selfie. “We will share our story about being here online, so our friends can follow,” he added. The couple had spent a night in Ella as part of their first, two-week trip through Sri Lanka.

Ella is brimming with similar accounts from outdoorsy young travellers drawn to explore the rugged slopes, scale the rocky mountains or take pictures in front of trains rumbling over the towering, nine-arch stone bridge built during the British colonial era. At night, they pack the small restaurants, tea shops and the few bars, chattering in a mix of languages from across the globe.

The town is unrecognisable from how it used to be promoted in Sri Lankan brochures – little more than a stopping point for a cup of tea to break up a journey. Residents put the change down to social media, travel blogs and platforms like Airbnb, Booking.com and Agoda. Local incomes have been boosted by offering rooms in private homes to smartphone-savvy foreigners seeking genuine local experiences.

“When they come to our place, we do not treat them as guests, but as our relatives,” said Jagath Weerakoone, who has seen a steady flow of international travellers since he opened his house, nestled in a wooded hillside, five years ago. “This is the difference with homestay; we do it with our heart.”

Veteran hoteliers are equally quick to credit social media for putting Ella on the world tourism map. It became a draw as young backpackers began arriving by train, said Inthikab Alam, general manager of a high-end hotel surrounded by tea fields. “Ella’s attraction is the outdoors and its cool climate. That is what they write on Facebook.”