Saturday Feb 14, 2026

Saturday Feb 14, 2026

Saturday, 2 April 2016 00:07 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

View from one end

View from the other end

From blocks to boulders

From top of the rock

It was a four-day Easter weekend break for everyone and many used it to get away to the countryside from the busy city environment. Our choice was Wave Rock, a four-hour drive from Perth along with Brookton Highway but invariably takes longer with short breaks on the way for tea, lunch and sight-seeing. It happened to be a rainy day and when we reached Hyden, the town closest to Wave Rock we decided to take it easy and hope for better weather the following day to climb Wave Rock.

We got up to a brighter morning. Yet armed with raincoats and warm clothes to beat a possible shower and blowing winds, we reached Wave Rock pretty quickly being just a 3km drive from Heyden. A quick run-through of the history of the place and what to look for on well-illustrated display panels and we were on the well-laid-out track, getting a glimpse of the rock through the trees. Soon we were at the foot of the world famous Wave Rock (part of Heyden Rock) and true to its name, it resembled a huge wave. Waves on a rock!

It is believed to be 27 million years old and made up of grey and red granite strips. Wave Rock hangs over like an incredible 15m high wave, about to break. It’s 100m long. The young and old spend time to pose for photographs imagining they are among the waves!

Its formation has fascinated geologists and the public for years and is one of many interestingly shaped rocky outcrops in the area. A note on Wave Rock says that it is a granite inselberg that has been weathered over millions of years by wind and rainwater. These forces of erosion have slowly swept the rock into the deep grey, red, ochre and sandy-striped wave that is seen today. The different colours of the rock have been caused by minerals being washed down the rock.

Another note explains that the shape of the “wave” is not caused directly by water erosion, but by scarp foot weathering. The rock was originally buried by soil, and as the soil level was lowered by erosion the top of the granite was exposed. As the granite is impervious, the rainwater ran down the sides and in the moist soil around the rock humic acid dissolved away the rock while it was still buried. The soil has since been eroded down to the rock surface that surrounds Wave Rock.

The curved shape of Wave Rock is emphasized by the vertical streaks of algae that run along its surface. The algae turns the stone a black colour that turns to brown during the dry season. At different times of the day Wave Rock changes colour; many a photographer has enjoyed its ability to play with light and perspective. In fact, it had been a photograph taken by Jay Hodges which made Wave Rock so famous. At the 1964-65 New York World Photography Fair his photograph won world recognition. The National Geographic magazine later carried the picture which created worldwide awareness of Wave Rock.

At the end of the Wave Rock are well-maintained steps and chains to climb the rock. Being a clear day the view from top covering a vast area was marvellous. A wall lies above Wave Rock and about halfway up Hyden Rock and follows the contours of the wall. It collects and funnels rainwater to a storage dam. A reservoir has been built on top to supply water to the Heyden township.

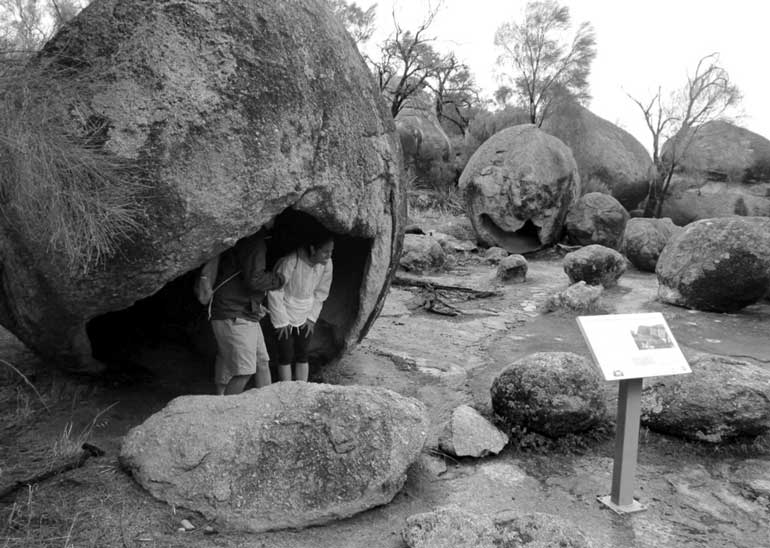

Back at the bottom of the rock, we found several walking trails with clear instructions where they would take us. We walked down ‘The Breakers Trail’ where we saw a cluster of boulders which had earlier been a sheet of rock. An explanatory display board said: In granite it is common for sheets to fracture into a series of joints, often either parallel or at right angles. When water penetrates down these fractures it weathers to rick it comes into contact with. The corners and edges weather quickest, as they are under attack from several directions at once. This begins to produce rounded or spheroidal rocks called ‘corestones’. When the rubble between them washes away they are left stranded with the supporting rock as boulders.

(More to follow.)