Wednesday Feb 12, 2025

Wednesday Feb 12, 2025

Saturday, 12 September 2015 00:02 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

''Sri Lanka is one of the best locations in the world, if not the best, for wildlife tourism, asserts naturalist Gehan de Silva Wijeyaratne''

Gehan addressing the gathering - pic courtesy Virtusa

By Himal Kotelawala

Picture this: You’re a traveller from Western Europe with a penchant for amateur photography and a keen eye for all things wild (in a strictly flora and fauna kind of sense). You’ve dabbled in wildlife photography before, but being limited to the cold and at times desolate and unforgiving environs of your continent as you are, when it comes to capturing big game or exotic birds in their natural habitat, you aren’t exactly spoilt for choice. So, wishing to expand your horizons, you decide to hit the great outdoors, armed with your brand new DSLR camera and 300mm zoom lens, as far away from home as possible. But where do you go?

Suddenly, your options seem endless. If you want to see wild elephants or big cats, there is the Serengeti in Eastern Africa. If it is lush tropical rainforests you’re after, there is the Amazon in South America. You want to see blue whales? Try the pacific coast off North America. But, you wonder, what if you want to see them all in one go (without heading to the zoo or tuning into Animal Planet)? If only there was one place on Earth where you could try all of this at once. One place that offered you a vast variety of amazing creatures, wild and free, found nowhere else in the world.

Buzzing with newfound enthusiasm, you do your research and you find that there is, in fact, such a place. It’s the perfect getaway, with its breath-taking golden beaches, misty mountains and a rich cultural heritage that goes back millennia – anda treasure trove for naturalists, hippies, beach bums, wildlife enthusiasts and thrill seekers alike. A little tropical island north of the equator, just south of India, called Sri Lanka.

This scenario is naturalist Gehan de Silva Wijeyaratne’s dream come true. A crusader for the twin causes of wildlife promotion and conservation, Gehan contends – andhe makes a pretty convincing case for it – thatSri Lanka is one of the best locations in the world, if not the best, for wildlife tourism.

“Sri Lanka has it all”

This writer had the good fortune to listen to Gehan speak on this very topic, at a public lecture organised by the Virtusa Corporation last Tuesday. And what he revealed there was nothing short of mind blowing.

“Sri Lanka has it all. In terms of the proverbial complete package, Sri Lanka is unparalleled,” he says.

In his line of work, Gehan often runs into sceptics who question the validity of this claim. And it’s not hard to see why. When contrasted with the big game found in Africa and the massive rainforests of Malaysia and elsewhere, conventional wisdom says that Sri Lanka couldn’t possibly be home to the kind of widespread biodiversity that would attract international wildlife tourists. This, says Gehan, couldn’t be further from the truth.

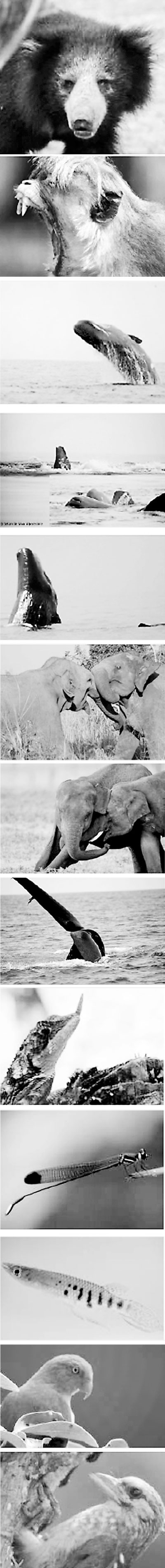

“You can go to Mirissa and see blue whales, sperm whales and dolphins. And then you can drive a bit further down south and see leopards in Yala. There aren’t many countries in the world where you get this combination,” he says.

The kind of combination, argues Gehan, that could have unprecedented economic dividends for the country in terms of foreign revenue.

“Wildlife has many dimensions. Remember we’re still a poor/middle income country, and we need to use our assets to generate revenue and uplift the state of the country economically. Singapore doesn’t have the kind of wildlife we have, but they’re still very good in how they manage their wildlife nature reserves. We have so much more, and we need to develop that in the way Singapore and London have done with their limited resources,” says Gehan.

Let’s do the math.

There is a huge number of international tourists coming to Mirissa every year for whale watching alone. Supposing the Department of Wildlife values a guest at $ 50 for a single boat trip, for a thousand guests, the total would be $ 50,000. Each guest brings with them at least a 1,000 dollars – probablymore, for accommodation, transport, etc.– andif you add up the revenue from just 200 trips, that’s a lot of foreign money coming into the country.

Gehan estimates that wildlife tourism in Sri Lanka maybe worth 40-50, maybe even a 100 million dollars. Pretty crazy.

And with the advent of social media, this figure is only going to go up.

“If you go on a trip, and you flood Facebook with pictures of whales and motivate others to come to Sri Lanka rather than go to, says, the Maldives or the Caribbean, it could do wonders for tourism in Sri Lanka,” says Gehan.

And why wouldn’t they opt to come here? As Gehan points out, during your stay in Sri Lanka, you can catch some rays on the beach, see some whales in Mirissa or Kalpitiya, go on a leopard safari in Yala and marvel at the wild elephants in Wilpattu or Minneriya. (Minneriya is home to the largest annual gathering of wild elephants in the world).

“I don’t think there is awareness of how much money wildlife tourism is generating for this country. In 2008, we used minimum rates and did a calculation (with room charges, etc.) and the total came up to about a billion rupees. Now, post war, rates have doubled; there are more rooms available, and thanks to internationally produced documentaries spreading the word globally, the figure has probably doubled or tripled,” he says.

Gehan himself had a part to play in the recently released Wild Sri Lanka: a National Geographic special. His book, also titled Wild Sri Lanka, served as the basis for the hugely successful documentary that included, among other things, awe inspiring underwater footage of a super-pod of sperm whales. (Incidentally, Sri Lanka offers the best chance in the world for spotting super-pods of sperm whales).

And then there are the birds. According to Gehan, half the scientific orders of birds found in the world can be spotted in Sri Lanka – some endemic, some migratory.

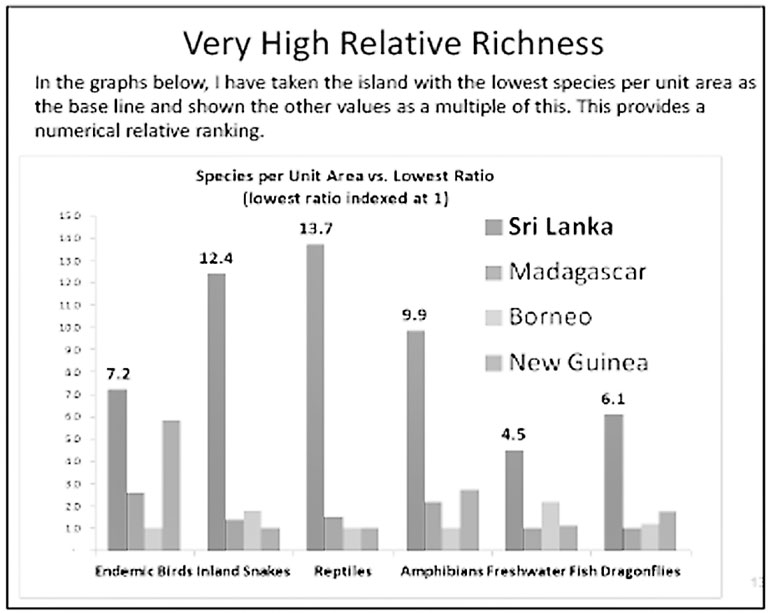

Sri Lanka’s reptile population is 14 times richer per unit area than some of the bigger islands such as Madagascar and Borneo (about 350 species of reptiles in total – “notso reassuring, is it,” he adds with a chuckle).

Three key factors

Gehan has identified three factors that make Sri Lanka so disproportionately rich for wildlife:

Physical factors – acontinental island, monsoons, isolated physically from India for a long time which has allowed species to become endemic. Sri Lanka has 103 river systems and deep seas close to the island which brings whales closer in(especially sperm whales normally found in deep waters).

Evolutionary factors – suchas land-bridge connections and species radiations.

Human factor – landthat had been cultivated in ancient times, the Minneriya and Kaudullatanks, etc., after they went wild, provided water for elephants. Leopards, too, have a high density in Yala due to man-made factors. Sri Lanka doesn’t have any natural lakes other than the villus in Wilpattu, says Gehan. All water bodies in Yala are man-made, providing grazing ground for spotted deer – forestscleared over a thousand years ago now functioning as grasslands, ideal conditions for spotted deer. A thriving deer population, naturally, means a lot of leopards

High species richness

According to Gehan, for an island so small, Sri Lanka has a surprisingly and astonishingly high species richness per unit area. Higher than most countries.

“You might think that Sri Lanka is small, but you can see how much more relatively rich Sri Lanka is. If we as Sri Lankans don’t realise that something very special has been going on in this country, how do we tell other people? We need to get the message out,” says Gehan.

Exactly how did such a small island become home to such diverse wildlife?

Gehan says a tempting and intuitive answer could be Ice Ages that happened in Europe, of all places, creating land bridges between India and Sri Lanka

“Massive amounts of water evaporated off the ocean and deposited as ice on land. Europe was completely frozen. The ice was so thick that the land actually sunk several kilometres under its weight. You can imagine how much ice there was. As a result, so much water came off the ocean that the sea level fell. As this happened, areas off Mannar in Sri Lanka became land,” he said.

This provided the perfect opportunity for animals on the Indian mainland to make their way to this country.

But Gehan isn’t convinced. It cannot possibly be that straightforward.

“When biologists do phylogenetic molecular analysis using DNA, they can work out when these speciation events took place, when this richness of species in Sri Lanka happened (about 40 million years ago. Unfortunately the convenient explanation doesn’t work,” he says.

We may never know what exactly led to this turn of events that led to our current abundance of wildlife, but that’s okay, says Gehan.

“It remains a mystery, but it doesn’t matter. Science doesn’t quite have all the answers, but we know we live in an incredibly special island,” he says.

Conservation through commerce

Gehan is a pioneering and prominent figure in wild life promotion and conservation in Sri Lanka. His love for the country and its biosphere is obvious. A civil engineer and chartered accountant by profession, he has worked on the basis that conservation can be achieved through commerce.

“If wildlife can be branded to provide livelihoods, there is an economic rationale for conservation. It is easier for local communities to grasp this than the eco-system benefits which are nationally important,” he says.

Illustrating this point, Gihan says that it is easier for someone to conserve a rainforest if they can make money by leading wildlife tours rather than planting tea by encroaching into the forest.

“You could try to explain that if the rainforest is lost, that farmers hundreds of miles away will not have rain and their crops will fail. But for a person who has a family to support, they need an income, and you need to give them an alternative to clearing the forest,” he says.

Pix courtesy Gehan De Silva Wijeyaratne

Discover Kapruka, the leading online shopping platform in Sri Lanka, where you can conveniently send Gifts and Flowers to your loved ones for any event including Valentine ’s Day. Explore a wide range of popular Shopping Categories on Kapruka, including Toys, Groceries, Electronics, Birthday Cakes, Fruits, Chocolates, Flower Bouquets, Clothing, Watches, Lingerie, Gift Sets and Jewellery. Also if you’re interested in selling with Kapruka, Partner Central by Kapruka is the best solution to start with. Moreover, through Kapruka Global Shop, you can also enjoy the convenience of purchasing products from renowned platforms like Amazon and eBay and have them delivered to Sri Lanka.

Discover Kapruka, the leading online shopping platform in Sri Lanka, where you can conveniently send Gifts and Flowers to your loved ones for any event including Valentine ’s Day. Explore a wide range of popular Shopping Categories on Kapruka, including Toys, Groceries, Electronics, Birthday Cakes, Fruits, Chocolates, Flower Bouquets, Clothing, Watches, Lingerie, Gift Sets and Jewellery. Also if you’re interested in selling with Kapruka, Partner Central by Kapruka is the best solution to start with. Moreover, through Kapruka Global Shop, you can also enjoy the convenience of purchasing products from renowned platforms like Amazon and eBay and have them delivered to Sri Lanka.