Tuesday Feb 17, 2026

Tuesday Feb 17, 2026

Saturday, 2 September 2023 00:20 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

This article is a case study from a remote interior of Dambulla, Sri Lanka, of a typical extremely remote dwelling holder of rare traditional medicinal knowledge of the Sinhala ‘paramparika wedakama’.

To know that it is inane to ask him to get together documentations and sit exams or come to Colombo to get himself ‘registered’ according to the regulations, one has to traverse into the rural wilderness, torn by drought and floods, the soil entrapped by synthetic fertiliser and the people resigned to perpetual poverty.

To reach the man we are going to describe, one has to veer off tarred roads and follow the twists and turns of shrubs and now brown grasslands, dry forests, pass wide expanses of earth on which paddy is grown using not traditional rice varieties but purchased high yielding imported seeds. To talk here of organic agriculture would be like talking Greek. A memory of how their parents would have farmed the land lingers but not a single farmer in the area is free from imported fertiliser that drains money from the land and sickens its people.

“Yes, everyone is sick. But they do not come to me. They go to the big hospital far away in the town,” says this sixty one year old ‘paramparika’ physician. He appeals for his name or exact residence not to be publicised.

“The last time they heard of me a team of Ayurveda doctors came and sat around here for hours no end writing down endlessly the remedies I use. They wanted me to register. I said my father and grandfather never did and that even if I wanted to that it is not practical. To this village I am just a poverty stricken man who is struggling to get the soil to yield and who also commits the crime of putting to it weedicide, pesticide and chemical fertiliser. We were farmers, my father and grandfather but we were physicians as far as we remember.”

Holding an exceedingly calm and benevolent persona even a brief exchange with him one gets the feel that he is able to ‘scan’ with his gaze the physical condition of an individual, an ability many ‘weda mahattayas’ of ore had. Their consciousness was unsullied and their intention was to ensure any human being they met was cured.

“Your joints seem of a weak nature. You should drink the juice of the ‘divul’ tree leaves,” he tells me. He asks to see my pulse and then realises it’s a particular day in a week and a particular noon time when it is not advised to check the ‘naadi’ of a person.

This physician specialises in ‘kadum bindum wedakama’ (treating limb breakages) and also the venom removing forms of medications especially for snake bites.

Below is his verbatim narration:

“Sometimes I do not know where people find my whereabouts but they come through these ‘kele’ (jungles) to see me from as far back as Colombo. I do not treat for venomous bites much now – it is increasingly hard to find the herbs – but a close relative does the treatment specifically for poisonous insect and snake bites. He is far more reclusive than me. He hardly speaks and only identifies himself as a farmer. At times when a serious patient comes I alert him and he treats.”

“There are some insects where one has to somehow kill the insect which has bitten the human immediately after. Or else the patient will never recover. After stinging the reptile or insect will linger somewhere close. Often one can identify it. The ‘Diya Makuluwa’ is one such insect. But you have to kill it not when it is in a hunched position but when it is straightened out. If you kill it when it is hunched then the body of the human it has bitten will be shivering continually just as this insect.”

The other terribly poisonous creature is the ‘Hikenella’. In case of snakebites the day of the week and the time of the sting impact how venomous it is. On a Wednesday the venomous nature of the sting is very low. On a Saturday or a Sunday it may be comparatively high. There are ancient books that we use for these. I had many very old ‘puskola poth’ (ola leaf manuscripts) which come down from so many generations. Some were used so much and so old that they were falling apart. I gave it for safekeeping to another relative who knows these ‘shasthras’.”

He explains that his most proficient treatment is in ‘kadum bindum’ (healing breakages of joints and limbs).

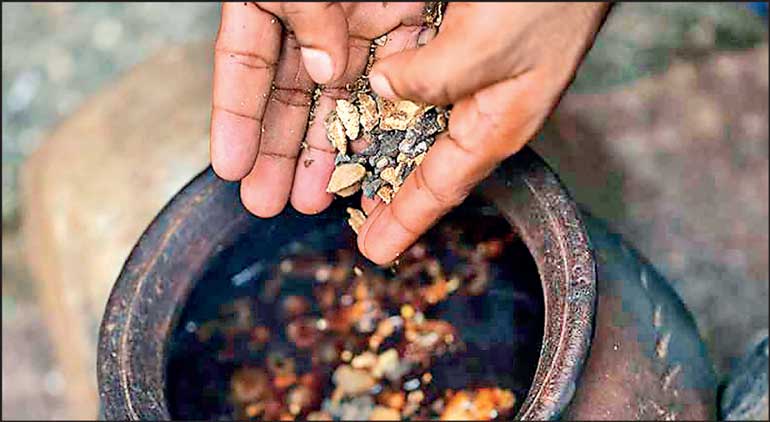

“There are hundreds of leaf varieties or herbs that we use to place together and re-fix limbs. These herbs are so powerful that if used on a normal limb without breakages then the limbs will fall off. They melt the limbs. These herbs were those that were used to melt even rocks in the age of kings. Intricate carvings were etched after the rocks were made like clay applying these portent leaves. In the same manner the bones that are broken are remoulded when the oil made of these herbs are amply applied and when the bandages are put in place (paththu).” Different oil bases are used. Many still remain secrets that are not revealed. If you put a modern price to such oils it will cost thousands of rupees.

“To fix a limb it takes only few hours. Just eight hours will do for the limbs to align itself when the most powerful leaf varieties are used. But of course we ask the patient to keep the ‘paththu’ on for days and not move the limb. It is important the limbs are not moved.”

How does he get the leaf varieties? Is it easy to obtain?

“That is like obtaining gold now. I have to use marathon runner type of youth of the village to seek high and low for these herb varieties. Often they have to go far to other areas by bus and walk again miles and miles. In this drought daily trees are dying. Dhan inthin winasa wela iwarai okkoma (now everything is destroyed),” he says with moist eyes.

Although he desperately needs the money he belongs to the ‘paraparmparawa’ (lineage) of tradition physicians who never put a price to their medication or accept money into their hands.

Since he applied an oil on my legs that quite miraculously instantly stopped a pain I had from trekking through arduous routes for long, I surreptitiously placed some money on the table on which there is a Buddha statue and a statue of the elephant god Ghana and few other deity.

The correct way is to place the money on a betel leaf and place it at some place within reach of the physician.

Although he does not dwell on his poverty it is all around. The house in which he had built on his own land, after living for years in a temporary shelter in someone else’s land, is still almost fully incomplete – there are no doors or windows. There is no furniture except a few old chairs. He has a daughter whose son is employed in a hotel in Tissamaharama. The grandchildren are with him and his wife.

The greatness of a man is measured when he does not exploit a sacred profession. This man is one of the many lineage based Sinhala ‘wedakam’ physicians – of lineages which once served monarchs of this land – who did not revile any branch of medicinal knowledge as long as it served humanity and whose basic philosophy of treating a human, animal or plant, is Buddhistic.”

“We want everybody to be well, isn’t it nona? Is not that how it should be. I am now asked to come to Tissamaharama to examine a few patients who need some limb based treatment. I am going there in a few days’ time,” he says.

“Please do not take my photo or mention my name. No need nona. We never exhibited or publicised ourselves. That is against this profession. Now I have a few more years and I will continue what was done for generations,” he states.

In his eyes is sadness. It is the sadness of Sri Lanka – a nation which has not protected, promoted and conserved in practice the indigenous health/wealth of this nation – the ‘paramparika wedakama’. Hundreds more traditional physicians will leave this earth in this land – unheralded and unsung. With them will die the last sighs of a nation killing all that is ancient in the ignorance that what is ancient is not valid today. (SV)