Monday Feb 23, 2026

Monday Feb 23, 2026

Saturday, 18 March 2023 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Surya Vishwa

Poetry could be described as the intersection between the tear and the smile, the juncture where life meets its reflective shadow and speaks in the dialect of the heart. True to the spirit of the Harmony page we dedicate this edition to the commemoration of World Poetry Day which falls on 21 March. We will discuss a few poems from the international realm and especially from Sri Lanka, featuring the concept of Thribasha – celebrating Sinhalese, Tamil and English poetry and the writers who write them.

Poetry is by itself a historical narrative from which we can learn about a nation, its spirituality and the lives of the people who live/d in it. Thus, poetry becomes the ever living pulse of a country. The ancient civilisation of Sri Lanka is a poetic testimony by itself which thrived in the medieval tradition of poetic letters – Sandeshiya Kavi sangraha such as the Hansa Sandeshiya, (messages of the swan) Salalihini Sandeshaya and the Gira Sandeshiya (messages of the myna) and those such as Amavatura, Pujavaliya and the Saddharma Ratnavaliya which give insight into the geography, traditions, policies, devoutness and overall way of life of the particular era.

Similarly in the Sinhala and Tamil language ola leaf manuscripts – whether the content is on ceremonies and traditions, astrology, medicine, farming or culinary knowledge, much of it was passed on in the poetic form, at times in a complex and coded manner.

All this show us that poetry is much more than lyrical language but rather the sinews that bind one human being to another and a nation to the world.

Poetry is also a weapon. It is the blade that opens up public consciousness. It is also the ladder that can breach the high walls of tyranny and help to shape policies that return to people their dignity.

Poetry is also a weapon. It is the blade that opens up public consciousness. It is also the ladder that can breach the high walls of tyranny and help to shape policies that return to people their dignity.

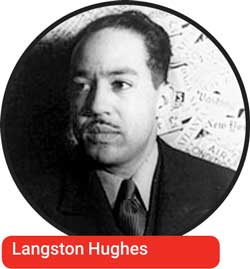

From the poetry of those such as Langston Hughes and Countee Cullen of the Harlem Renaissance which led to the Civil Rights movement in the early 20th century in the United States and the poetry of women such as Sylvia Plath which started off the feminist movement as well as the contemporary poetry of spiritual masters like the Vietnamese Buddhist monk Thich Nhat Hanh – we are being told – if we care to listen, that all of life is an unfolding poem.

Let us begin listening with the following poem, the title of which is ‘Call me by my true names’ by Ven. Thich Nhat Han.

Do not say that I’ll depart tomorrow

because even today I still arrive.

Look deeply: I arrive in every second

to be a bud on a spring branch,

to be a tiny bird, with wings still fragile,

learning to sing in my new nest,

to be a caterpillar in the heart of a flower,

to be a jewel hiding itself in a stone.

I still arrive, in order to laugh and to cry,

in order to fear and to hope.

The rhythm of my heart is the birth and

death of all that are alive.

I am the mayfly metamorphosing on the surface of the river,

and I am the bird which, when spring comes, arrives in time

to eat the mayfly.

I am the frog swimming happily in the clear pond,

I am the frog swimming happily in the clear pond,

and I am also the grass-snake who, approaching in silence,

feeds itself on the frog.

I am the child in Uganda, all skin and bones,

my legs as thin as bamboo sticks,

and I am the arms merchant, selling deadly weapons to Uganda.

I am the twelve-year-old girl, refugee on a small boat,

who throws herself into the ocean after being raped by a sea pirate,

and I am the pirate, my heart not yet capable of seeing and loving.

I am a member of the politburo, with plenty of power in my hands,

and I am the man who has to pay his “debt of blood” to, my people,

dying slowly in a forced labor camp.

My joy is like spring, so warm it makes flowers bloom in all walks of life.

My pain is like a river of tears, so full it fills the four oceans.

Please call me by my true names,

so I can hear all my cries and laughs at once,

so I can see that my joy and pain are one.

Please call me by my true names,

so I can wake up,

and so the door of my heart can be left open,

the door of compassion.

This is the epitome of a poem that speaks of the wisdom of loving kindness amidst the worst of atrocities where one could see within oneself and others the hidden or un-awakened good. Here the entire life process within and beyond each birth cycle is metaphorically presented as a seamless evolution process in which we could awaken the compassion in each of us.

Let us now listen to the poetic cry for justice by Langston Hughes, the novelist, playwright and poet who was a pioneer of the Harlem Renaissance that created the literary foundation for the emergence of the Civil Rights Movement. This poem is titled ‘Justice’.

That Justice is a blind goddess

Is a thing to which we black are wise:

Her bandage hides two festering sores

That once perhaps were eyes

Wherever we are in the world, we can resonate with these four lines as we find justice to be elusive and shrouded in power, hypocrisy or manipulation.

Let us now look at a poem written in the early 1970s by Denagama Siriwardena in his first poetry collection titled after one of the poems in the book; ‘Aney Mage Nadu Asanu’ (which can be translated as ‘Oh heed my call for justice’). Below is the translation of this poem.

To the house of a man

To the house of a man

Who travels in a Benz car

Went my sister

Like a little flower bud

A long time thereafter

Carrying a blossom

She returned to the village

Crushed and wilted

Like a faded flower

Against the Benz car owner

Father filed legal action

Another man

Who also travels in a Benz car

Judged this case

Father, who lost this lawsuit

Now narrates it

To all, on the highroads

Father

There is still no power

Vested on those who walk

To mete out justice

As in the poem by Langston Hughes we see here too how the poet sees what we refer to as justice as played out in different dimensions of society. While in the case of Hughes it was reflective of power tinted by racial superiority and division, in the case of the poem by Siriwardena it is about the utopian notion of justice when faced with class and wealth based boundaries. He shows in the poem how this nullifies the presumption of equality and makes Justice a redundant entity.

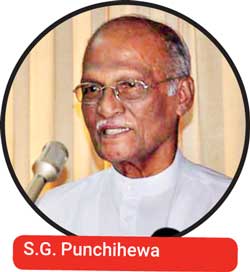

We now look at a poem from the collection Thisahamige Kavi (poems of the oral tradition composed by Thisahamy), the Veddha chief of Sri Lanka, by S.G. Punchihewa. Punchihewa, like Denagama Siriwardena is a veteran poet and literary figure writing in the Sinhala language for around six decades. It should be mentioned here that S.G. Punchihewa celebrated his 90th birthday on 15 March amidst a special literary event organised to commemorate a lifetime in the printed world thus far. This book, published in 2013, was amongst the work that were showcased at the event and is about the orally passed down sung poems by the Sri Lankan aborigine Veddha leader Thisahamy who died in 1953 (not to be confused with the subsequent Veddha leader and others under this name). As pointed out by S.G. Punchihewa, the life story of Thissahamy was featured in the book Savage sanctuary by R.L. Spittel and the poems of this book is from the hundreds of poems Thisahamy composed and sung out, describing diverse situations of his life including his ousting from the village. These poems are those instilled in the memory of his son Tikiri Wanniya and selected by S.G. Punchihewa for the book.

We now look at a poem from the collection Thisahamige Kavi (poems of the oral tradition composed by Thisahamy), the Veddha chief of Sri Lanka, by S.G. Punchihewa. Punchihewa, like Denagama Siriwardena is a veteran poet and literary figure writing in the Sinhala language for around six decades. It should be mentioned here that S.G. Punchihewa celebrated his 90th birthday on 15 March amidst a special literary event organised to commemorate a lifetime in the printed world thus far. This book, published in 2013, was amongst the work that were showcased at the event and is about the orally passed down sung poems by the Sri Lankan aborigine Veddha leader Thisahamy who died in 1953 (not to be confused with the subsequent Veddha leader and others under this name). As pointed out by S.G. Punchihewa, the life story of Thissahamy was featured in the book Savage sanctuary by R.L. Spittel and the poems of this book is from the hundreds of poems Thisahamy composed and sung out, describing diverse situations of his life including his ousting from the village. These poems are those instilled in the memory of his son Tikiri Wanniya and selected by S.G. Punchihewa for the book.

Below is a poem about treatment for snakebites which Thisahamy was said to have been proficient in.

We obtain medicinal treatment

Of the expertise perfected

In practice as seen

We seek out the mantras

The Anjanam, the auspicious smoke

Reptilian anger selects the fatal point

S.G. Punchihewa points out in describing this poem that the Veddhas believed that if a snake stings in wrath, that the poison of that anger is so vicious that no amount of treatment could save the patient. It is believed that a snakebite devoid of wrath or viciousness can be treated and the poison removed from the body.

This brings us to the understanding of the poison that the emotion anger contains, whether it is in the form of a snakebite or emanating as a sting in the human heart as dweshaya (resentment).

We now look at the poetry of Ratnashri Wijesinghe whose poetic works include the books Suba Udesana (auspicious morning), Mal Ahura (bouquet of flowers), Wassanen Pasuwa (after the rain), Suwanda Muwadara (the hovering scent) and Sandagiri Pamula (feet of the rock).

We have selected the poem Sigiri Apsarawa Kendang Ennada (Shall I bring home a Sigiri damsel – of the frescos fame) from his book Mal Ahura.

I seek permission mother

To bring home

A Sigiri damsel

The Poya moon

Has also come to the village

To leave

I seek your permission mother

She has lineage to royalty

From both parents

Her chastity

Is as pure as borne from flowers

In delicate beauty

She is a true goddess

In this book Ratnasri Wijesinghe does what few poets do – give the background analysis of the poem as well as the event from which the inspiration to write it sprang up. It is thus described that this poem is based on the very commonly seen parental opposition to marriage based on class, caste, ethnicity or other friction which much family based social opinions are formed. It is stated by the author that this poem was inspired by the cynical response an unmarried friend gave his parents (who had opposed all his choices) when they inquired from their ageing bachelor son as to when he would marry. This poem has been put into music by H.M. Jayawardena and sung by Asanga Priyamantha Peiris.

In this book Ratnasri Wijesinghe does what few poets do – give the background analysis of the poem as well as the event from which the inspiration to write it sprang up. It is thus described that this poem is based on the very commonly seen parental opposition to marriage based on class, caste, ethnicity or other friction which much family based social opinions are formed. It is stated by the author that this poem was inspired by the cynical response an unmarried friend gave his parents (who had opposed all his choices) when they inquired from their ageing bachelor son as to when he would marry. This poem has been put into music by H.M. Jayawardena and sung by Asanga Priyamantha Peiris.

We now feature the poetry of a young poet, Nayomi Amarasinghe, member of the Kalutara Writers’ Association. This poem is part of an unpublished collection provided to the Harmony page for this edition. These poems are written similar to the Haiku tradition. The writer is in the process of attempting to publish her poetry in book form and what has stopped her so far is the difficulty in raising funds for it.

We have selected three such poems where the meaning and metaphor as well as nuances are self-explanatory.

The birds

In the pet shop

Can also feel the air

Look at this row of ants

How they greet

Without ending their journey

The sunrise and sun set

Is watched

Silently

By that mountain

We now feature the English poem ‘Thus I have heard’, from the book ‘Sedahamy Selvakumari and Others’ by Sakunthala Sachithanandan.

This craving for Merit, I heard on Poya day

This craving for Merit, I heard on Poya day

(and thus have I heard before)

Is part of the I and Me and My

And tainted with Self, at the core

Did that good deed go into my account of pin

Will it wipe out my load of meanness and sin

I’m planning My Program of Many Good Deeds

As I guess I will be soon going

Will this be your driving motivation

Hoping to get a Front seat in your new location

For your I and Me and My

If one could discern from an early age

That others felt the same hunger, fear and pain

As oneself and without thinking first

Of the Merit to be gained for oneself

One could be happy in other’s well being, give joy

That should be enough without plotting your ploys

Become aware, be wise, evolve

And as Khahil Gibran so wisely said

One should “be like the myrtle which perfumes the air

Unconsciously – without effort.”

And be kind and gentle because one just cannot help it.

To be continued next week

Sakunthala, a lawyer by profession and a veteran poet and children’s story writer throws light on the panic to do good that befalls on us when we near the end of our journey and we do not want to suffer wherever it is we may end up. She juxtaposes this craving to get pin for afterlife comfort, which in essence is selfish because it does not spring from acts of kindness to others as one would do for oneself but rather something that is done as yet another accumulation for one’s own benefit.

She quotes in the poem a line from the Lebanese origin poet Kahlil Gibran who was a stringent critic of the hypocrisy of early Christian Orthodoxy and wrote about idyllic humanistic and non-attached love that is notably described in his masterpiece ‘The Prophet’.

We now feature another poem by Sakunthala Sachithanandan from her book ‘On the Streets and Other Revelations’. This poem is titled ‘Riches’.

I sit, my many riches spread about me.

I glory in the feeling that we are millionaires, no less

So fortunate, so blessed

With so much, it makes me giddy to just glimpse

Under this very table, at my feet about a hundred

And there, under another, perhaps another hundred

Over there, again, they lie, about a hundred and fifty

I tremble in the knowledge that they are ours!

No common baubles these, although

In the sun they hung and swung

On the Karutha Colomban tree slowly ripening

Joyfully eaten, chewed up, dropped

By the hungry squirrels, birds and bats

To fall and rot, blue bottles all a-buzz!

Sometimes we will step on one

And to our unsuspecting toes

Would stick the golden, yellow, smelly pulp

Here they life in all their green gold glory!

Splendid, mute and plump, mat skinned and heavy

Their promise wafting up in their heady scent

Signaling what is yet to come – and then the skin

Peels off like strips of plastic to reveal

Swollen orange flesh with a myriad drains

Marking the route of the skin’s miniscule veins

A feast follows then – the first ecstatic bite

And the other, luscious morsels of delight

As often as we give away these treasures

To kith and kin and friends – this generous tree

Bears another load and yet again another,

Offering us its bounty for the season

The birds and bats and squirrels go on feasting

They’re hungry to be rich and so are we!

The poem details out the generous abundance of nature through the description of a Karutha Columbaan mango tree – the iconic mango variety of Jaffna – the North of Sri Lanka.

We now feature a poem from the collection ‘Rhythm of life’ by Psychiatrist and author Dr. Ruwan M. Jayatunga. This poem is titled ‘A Schizophrenic – Please don’t label me’.

My world is limited

Filled with wired sounds

I see Rocky Marciano

Fighting with Woody Allen

Long time ago

Aliens abducted me

They fixed wires into my brain

Then sucked out my brain substance

I cannot control my thoughts

Because thoughts control me

Some kind of energy is inside me

Giving continuous commands

I hate to go to the Bush House in London

Where the BBC transmits by thoughts

People often express amusement

When they read my thoughts

A man with a black jacket

Is an agent of the KGB

He is spying and trying to track me down

Maybe he wants to take me to Moscow

I was in Lubianka

As questioned by Lorenthy Beria

I was released by the NKVD

Then planted in Pennsylvania

When JFK was murdered

I knew the secret plot

No one took it seriously

Not even my psychiatrist

They called me a Schizophrenic

Branded me for the rest of my life

They said I could be a danger

Kept a watchful eye on me

Whatever I wore

I felt an invisible label behind my back

Probably it said

That I am a Schizophrenic

The poem is a sympathetic synopsis of how modern day clinical psychiatry may forever tarnish the future of a human being. It can motivate us to took deeply at how those of us who call ourselves sane – may be attitudinally imprisoning others in the jail of mental illness while not seeing our own aberrations.

We now feature a poem from the book Down Memory Lane by S. Pathmanathan (Sopa), one of the senior most poets from the North of Sri Lanka who at age 85 is still persistently pursuing his literary journey. The poetry is written in English and the book was launched last year. The poem we have selected is titled ‘Amma’s boys’.

It was a few weeks

after his wedding

Arul a was having breakfast

‘Egg isn’t properly fried!’

‘It is ok. I fried it myself’!

The new bride answered

‘Amma would do it better with just dry coconut leaves!’

‘I know you always prefer her delicacies!’

The focus of this dialogue was Periyamma

the eldest sister of my mother

Very traditional in her ways

skilled in maintaining the balance between salt and tamarind

She would do wonders with spices

a pinch of this

a pinch of that

Arul’s wife was reluctant to give in

‘Your people

add a lot of coconut milk

salt and tamarind!’

‘Essential ingredients, aren’t they?’

Arula vetoed her

Last month

my son was back home

He lives in Canada

with his wife and children

He’s in the kitchen

seated on the floor

relishing the kool

served by his mother

from the earthen pot!

I think wives have to put up

with the encomiums

their husbands shower

on their mothers

All husbands are amma’s boys

The poem is one among others through which the writer takes the reader through the path his birth and childhood trod upon and through the dialogues, hallways and occasional idiocracies of family and friends that we witness we can visualise a past that exists in the mind of the writer.

The book Down Memory Lane by S. Pathmanathan was translated into Sinhala under the direction of Professor of Athropology, Praneeth Abeysundara and featured as an online edition of the Jayawardenapura University Department of Anthropology website as a step to foster understanding between Sinhala and Tamil writers. The book was translated for the Jayewardenepura University by Kanishka Wijerathne, Daya Dissanayake and Oshada Abeysundara.

We now feature a poem by Cheran Rudhramoorthy, the expatriate Sri Lankan Tamil poet now living in Canada. A sociologist by profession Cheran was a journalist in Sri Lanka in the 1990s and has written much about the national misery of civil war and terror acts such as the burning of the Jaffna library.

A letter to a Sinhala friend (written in 1984)

It will not take many days

for you

and your friends

to recover from the shock

of meeting me, an ordinary man,

from an unseen and distant land

where, you had heard,

we sow lead-shots from guns

instead of seeds; a place

half full of two-storied houses,

half full of terrorists.

As we sat side by side

on the steps leading down

to the milky stretch of water

covered in glinting fine threads,

shreds of the moon’s curtain –

water that changed colour when its

muddy depths were stirred

and changed again with the shadows

of passing clouds –

my heart melted

when you sang a Sinhala song

in your sweet voice.

Once long ago –

I was a small boy then –

waiting at the Maho station

for the Batticaloa train,

I walked with my father for a while,

some distance along the railway lines.

Midnight.

The quiet sound of a lullaby

murmured through the wind.

The shock of that gentle sound

intercepting the baby’s cries

struck my heart that night

with sudden sadness.

Today too

I am enveloped by

a fine grief.

Did our different languages, after all,

put such distance between us

that we could not smile together,

nor savour

the beauty of falling ponnocchi flowers

blown down by the tumultuous Aadi winds,

nor those sudden moments of hesitation

when the long-tailed peacock

stopped and turned around in its stately walk?

I could not pluck for you

the single peacock feather you desired

nor, in the early hours of the night,

accompany you, as you wished,

across the moonlit grass

Your eyes could not hide

these small disappointments,

nor can I

forget your gentle affection.

We went our ways without maiming Nature,

leaving the flowers to blossom

and the grass to flourish

you to the south

and I to the north.

At daybreak, when

the cool breeze climbs down

from the huge trees

along the mountain ranges,

as you take your walk

brushing your teeth,

you will remember the days

when we worked together

excavating an ancient city at Maanthai,

and our brief friendship.

Tell your people

here, too, flowers bloom,

grass grows,

birds fly

As we read this poem we can keep in mind the context it was written in – the year the poem was written was cited as 1984 which marks the beginning of the unrest in the North that led to full-fledged armed conflict. While we may linguistically label or interpret in diverse ways the thirty years that followed, what remained at the core were dead bodies of human beings in their prime of youth. In between lay a chasm to be filled with understanding, empathy, caring and love. From 2009 we have had this chance and the biggest gift we could give each other being the gift of peace. Sri Lanka, a land in which Buddhism is enshrined, is a nation which can, each day, grow in discipline and kindness to give the world the message of peace.

The attempt of this edition of the Harmony page was to celebrate poetry – the language of the heart and although there were many other poets and poetry that we wanted to highlight, space limitation made us focus on a fragment instead. However, we will continue in this endeavour, especially through the Thribasha endeavour to promote translations and readings of literature in Sinhala, Tamil and English.