Tuesday Feb 17, 2026

Tuesday Feb 17, 2026

Saturday, 23 October 2021 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

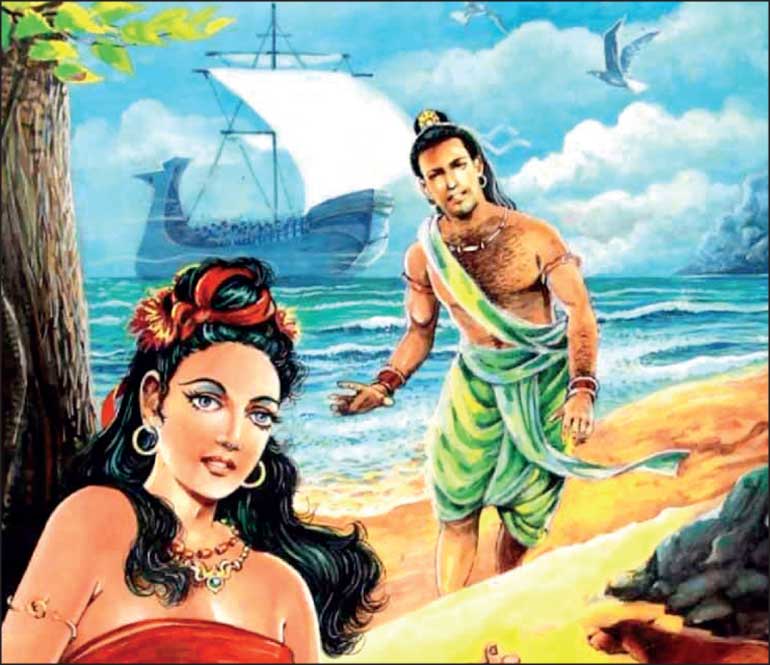

The significance of Vijaya’s arrival to Sri Lanka (Tambapanni) and what it portrays with regard to our culture provides us with lots of information about Sri Lanka’s history, culture, society, arts and crafts, and many more. This legend has many aspects, providing Sri Lankan scholars opportunity to look back into history and look for the root causes of the beginning of Sri Lankan culture, centuries before the arrival of Vijaya to the country from India

By Professor Prashanthi Narangoda

Folklore plays a major role in portraying one’s own culture and its identity at major scale. The term ‘folklore’ reflects many a domain representing the values, customs, norms, arts and crafts, and diverse aspects of living of the particular society.

It envisions the vast scope of elements that have been imparted from many eras down to contemporary society and its stake holders. The term folk is so vast and limitless in its essence. We cannot predict, assume, demarcate or define it in our words. We may establish our assumptions by taking into consideration the data and sources we have at present.

What we are mostly ignorant of or have neglected, in other words, is the root cause of the substance that we make assumptions upon and that may lead to several other pseudonyms, perhaps. Therefore, it necessary to explore the root causes of these elements, and identify in broader terms ‘what is folklore?’

The term ‘folklore’ is made of two words: ‘folk’ which means regional people and ‘lore’ as representing the vast area called ‘stories.’ Therefore, folklore reflects the ‘stories told by people in a particular region’. Folklore enables us to define a population’s values, beliefs, and preferred way of life with its literary themes.

One must not forget the fact that folklore was passed down from earlier generations, who told the stories verbally and shared through verbal communication. These were stored in the heart and mind and memorised by heart. Each generation would then tell their children these stories which became part of a culture’s tradition. Such genre was overthrown when the advent of printing became dominant to our cultures, and as a result, the printing press allowed these stories to be published – and shared with the world.

We being the customers and custodians of print media for today identify and categorise these folklore in different depths and breaths, naming them under different categories. In doing so we often ignore that these stories belong to an oral tradition of a forgotten era.

Thus, it is necessary to look back to the particular forgotten or ignored era that provides us with much consolidated information on culture and heritage of a nation in its very essence. It is first important to understand that folklore, or folk culture and the related concepts, ideas, and the philosophy is very much intangible and cannot be measured at one point.

It is so vast and its magnitude cannot be measured. It lives and evolves with time, reflecting one’s cultural elements from many diverse perspectives, continuing through generations.

Having understood the vast scope and the diverse aspects of the term ‘folklore’ it is necessary to study the significance of Vijaya’s arrival to Sri Lanka (Tambapanni) and what it portrays with regard to our culture. Indeed, it provides us with lots of information about Sri Lanka’s history, culture, society, arts and crafts, and many more.

It is evident that Vijaya’s arrival is identified as an incident that revived Sri Lanka’s culture and some believe that it civilised our culture. This is one interpretation. This interpretation holds that he became the ‘first king’ in the Sri Lankan history, as recorded in the Great Chronicle Mahavamsa. However, we must not forget the period prior to the arrival of Vijaya which is also described in the same Chronicle in this purview.

With such evidence, one may argue: ‘what was the nature of our heritage before the arrival of Vijaya to the country?’ Therefore, it is so important to examine the oral traditions in comparison with the available literary sources. We need to consider the three phases: 1) Life of this nation prior to the arrival of Vijaya 2) The incidents revolving around the arrival of Vijaya, and 3) the Coronation of Vijaya as the ‘king’ and the beginning of a new kingship of the country.

When we consider the first phase; life of this nation prior to the arrival of Vijaya, we have to look in to two major factors: the Ravana dynasty in Sri Lanka and later the arrival of the Lord Buddha three times.

According to the legends, Ravana belongs to clan of Yakka who ruled the island for a period during which he sustained the island with many comforts and welfare. The term Yakka should not be taken literally in our common understanding of the word in modern terms. This term has a very complex and highly-evolved dimension which we can ascertain by the recorded fact that he has provided education to the countrymen, while he underwent an Acharya to learn the Silpa.

According to the community understanding, Ravanacharya was an eminent scholar who wrote Padarathna, a commentary to the Rig veda. As per our knowledge, Ravana was an ardent Sun and Shiva worshipper and a researcher who first produced the air craft (pushpaka Vimana), a musician who was well versed with Vina, and a king who ruled with his own autonomy for centuries. Though, there are several stories about his birth, and even ruling, the Sri Lankan connotation is that he was born in Sri Lanka and ruled over yakka, deva and humans as well.

Thus, we must not forget that the island prior to the arrival of Vijaya was a well-sustained, highly-advanced community where people were treated in a very ‘civilised’ manner. ‘The Ramayana,’ the great Indian epic, explicitly describes the beauty of the country when the monkey king Hanuman secretly arrives to take back Sita, the fiancé of Indian king Rama held by the king Ravana.

Accordingly Sundara Kanda, the fifth chapter of the so-called epic, illustrates the pathway of Hanuman in the citadel of king Ravana when he went in search of Sita and where he finally found her in the Asoka Vathika, a beautiful garden endowed with fruits and flowers.

This legend has many more aspects to study, providing Sri Lankan scholars opportunity to look back into history, and to look for the root causes of the beginning of Sri Lankan culture, centuries before the arrival of Vijaya to the country from India.

According to the Great Chronicle, the Buddha visited three times, perhaps more than that, to many a places in the island in which Mahiyangana, Nagadeepa, and Kelaniya are highlighted due to the incidents described in the Mahavamsa. During all his visits, he has been able to convert other religious believers such as yakka, naga and deva as ardent Upasakas of Buddhism.

One such example is the yakka Sumana’s conversion as a Buddhist, and his pledge to safeguard the Buddha Dharma in the island from the peak of Sri Pada where the Buddha set his footprint (Buddha pada) which is venerated by the Buddhist all over the world to date as well as other religions practiced in Sri Lanka to day which gives a major unifying factor to present day life and this has to be dealt in a separate article.

Vijaya who arrived in the island with 700 colleagues following the banishment by his father from India is the successor to king Ravana. Vijaya was looking for a better place for his living, and the Sakra in the guise of a hermit informs him that the name of the island is Tambapanni and is a peaceful haven lush with nature’s bounty.

The banished Prince thus landed upon this island and was surprised to see the dark coloured woman, Kuveni who was spinning or weaving. He made the best effort to attract her by having a bath at the nearby pond and picking some lotus from the same pond according to Mahavamsa. However, she did not let the stranger to touch her and defended herself from the unexpected threat. However, she finally was wooed by the king who took her as his spouse.

The incident is so remarkable, because it showcases many a characteristic of Sri Lankan culture at the time of Vijaya’s arrival. The island had pursued a self-sustained economy and polity where the agriculture was the main earning and living, and the village administrative system was well established. Not only that the country had established its own customs, norms and affinities where arts, crafts, and performing arts being at its zenith.

All these can be illustrated and explicitly portrayed through the conversation between the Prince Vijaya and Kuveni at their first meeting in their private room well prepared by Kuveni. According to the recorded information sources, the Prince was so amazed by the sound of music from a nearby dwelling, that he questioned Kuveni about it.

Her explanation is so remarkable to us: according to her, the sound was the music of pancathurya nada, played by the village folk, to celebrate the wedding ceremony of the bride, the son of the leader of the neighbouring village to the daughter of another village leader. And Vijaya’s coronation as the first king of the island is to be questioned at this point because the incident provides us with abundant of information and stories with regard to Sri Lankan history, its culture, leadership/polity, economy and the customs, norms, practices and celebrations, all belonging to intangible cultural heritage.

Under such circumstances, it is very much important to consider folklore as a pivotal domain of evidence and a source of information to establish and interpret one’s own cultural values, its authenticities, identities and dignities of our era and use it for national unity. Vijaya’s arrival in this perspective can be considered a mirror in which we can Sri Lanka’s ancient culture and its intangible heritage; and this to re-visit and re-define how we can use its diverse aspects to build a cohesive, sustainable and harmonious nation.

[Prashanthi Narangoda is a Professor of Fine Arts, Department of Fine Arts, University of Kelaniya since 1992. She is the current Director of the SAARC Cultural Centre. She serves as a member of the Management Committee of the Gamapaha Wickramarachchi Ayurvedic Institute, University of Kelaniya. She obtained her Bachelor’s Degree of Fine Arts with a Second Class Upper Division Honours from the University of Kelaniya in 1992, and Master of Science Degree from the Post Graduate Institute of Archaeology, affiliated to University of Kelaniya in the year 2000. In 2012 she obtained her Doctor of Philosophy from the University of the West, California, USA. She also holds a Post Graduate Diploma in Architectural Conservation of Monuments and Site from the University of Moratuwa, Sri Lanka which she obtained in 1994. She bears the life membership of the Royal Asiatic Society (Ceylon Branch) since 2007, American Association of Religion (AAR) since 2010, and a member of the Scientific Committee of the UNESCO International Dance Council since 2016. She is also a member of the National Trustees Board.]