Tuesday Feb 24, 2026

Tuesday Feb 24, 2026

Saturday, 29 January 2022 00:25 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

|

By Surya Vishwa

|

Kulandai Shanmugalingam

|

Mayilvanagam Shanmugalingam, better known as Kulandai Shanmugalingam, is probably Sri Lanka’s oldest playwright and dramatist. He is certainly so in the north, having inaugurated the school of Drama and Theatre in Jaffna in 1978, two years after he followed the diploma in drama in Colombo. He is today 90 years old and venerated by the lecturers and students alike in Jaffna, especially those who are linked with drama and arts.

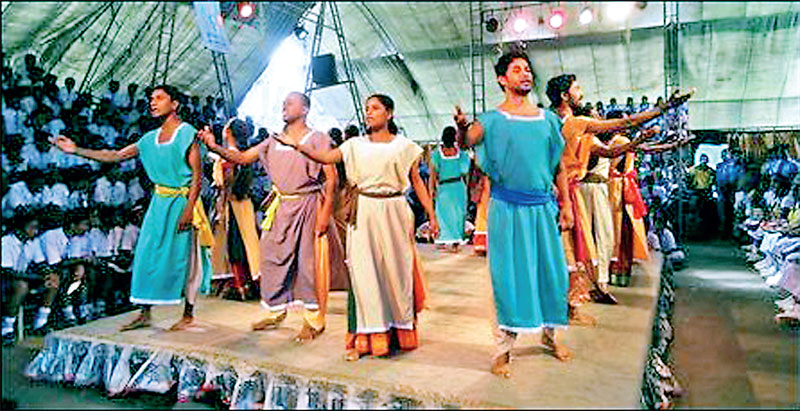

Among the general public of the north, he is a household name as he was the main provider of whatever little entertainment the general public could get during the years the north was engulfed in war. His plays revolved around issues faced by the common man and was a catharsis to the masses who had gone through much suffering. He has also primarily focused on writing plays for children so that diverse social messages could be communicated to them.

Pertaining to adult audiences, he has written much on themes connected to the north, such as those linked with the concept of home, displacement and migration. Man Sumantha Meniyar, (loosely translated as the sweat and dust on their shoulders – associated with peasants caught in the conflict) a sequel to his wartime plays, speaks of the untold story of the those who are connected with the soil i.e. the peasants in the backdrop of the conflict.

Several of his plays have been performed in Colombo. One of his later works, the script of Heaven with Hell translated to English by S. Pathmanathan and published by Kumaran publishers, is to be launched in February in Jaffna alongside the English version of the latest poetry collection by Pathmanathan (Sopa). The publication of the play Heaven with Hell is dedicated to Parakrama Niriella, founder of the Janakaraliya mobile theatre. The work is connected with the different social upheavels created by the conflict situation.

“During the war time there was an embargo on paper. Paper was more precious than gold to me then. I used to get papers from the teachers who used to go to exam duty as they would get some extra blank sheets,” states Kulandai Shanmugalingam. Like S. Pathmanathan (Sopa – the most senior and well-known poet in Jaffna) Kulandai never left the north as some of the elites did during and soon after the end of the war. Through the gunfire and varying intrigues, they maintained their integrity as independent analysts of the saga of their birthplace being destroyed for the purported goal of freedom which could be comprehended in many different ways.

Having had equal exposure to both the Sinhala and Tamil language (also English) as a child studying at a Catholic school in Bolawatta, he considers both languages as his mother tongues. He tells me so in fluent Sinhala devoid of the usual Tamil-tinged accent and says how his Sinhala friends comment on it. Throughout his uninhibited narration about his life to me, I kept on thinking how fortunate I was to meet him, something that even a Jaffna scholar doesn’t easily get a chance to.

|

My request to Sopa, to approach Kulandai on my behalf with a request for a meeting was at first met with scepticism. Sopa conveyed to me that it was futile as he had tried many times before to get appointments with Kulandai for several persons but had failed. I have also separately tried before in over two decades of consistent travel to the north to meet this recluse icon of northern drama but have not succeeded. Known for shunning publicity and people, he was known to promptly dismiss any requests for meetings.

This time probably the planets were probably rotating in my favour and I got not just one meeting but the opportunity to meet him over three consecutive days; the second and third day being with two of his students. One of them is Navaraj, a counsellor and psychiatrist who has learnt to use drama as an expressive art for healing. The other is Dr. D. Ratheetharan, teaching drama at the Jaffna University. Both of them are senior drama practitioners in their late forties and early fifties respectively.

Sopa who arranged the meeting with Kulandai was spellbound at the rare sequence of events which included the usually reticent Kulandai Shanmugalingam breaking into several acts such as when he acted the role of Krishna in a play from the Mahabharatha as well as his first ever act – carried out when he was yet a teenager imitating a toothless octogenarian who used to call out for a relative by the name of Maradamba.

Kulandai Shanmugalingam who has all his teeth (as well as his eyesight), has to take some effort to act like a toothless man and does so perfectly.

“This is the act that I first did for the cousins. I was a shy chap you see, and I did not go out of the house. When I finally joined the Young Men’s Hindu Association (YMHA) in my forties, my friends were joking as to who I was; whether I was indeed the same Kulandai. Kulandai means child in Tamil and is not my birth name. It is not my full birth name I am known publicly by but the pet name of Kulandai that has stuck to me for life. I am the youngest of five boys and that is by the term baby – Kulandai was first pasted on me,” he laughs. He displays his 90 years young eyesight by reading without glasses from a book with small print.

Endowed with a childlike simplicity that only geniuses are bestowed with by nature he continued to update me about his life.

Born in Jaffna but brought up in Bolawatta from age of three months to 10 years because his father as estate official served in that area at the time, he became familiar with Jaffna only after the age of 10. The house I meet him in, down Adiyapadam road in Jaffna is well over 100 years old. The ‘newer’ section of the house, the front portion of the extension was built by his mother when she was pregnant with his eldest brother who if alive should be 100 years this year. Thus, technically the older section of the house is around 150 years.

“This house is called Thayaham which means Mother’s place and can be also interpreted as Motherland,” he says. “Just like we say for Sri Lanka – Mawbhoomi,” he states. He then breaks into literati Sinhala, the kind of which seems too high flown for me that I phone up Priyantha Dayaratna, a Wastu engineer who was teaching at the University of Visual and Performing Arts. Priyantha who is about 40 years younger than Kulandai is exceedly lucky for the first ever chance to connect with a dramatist from Jaffna and speaks with the usual high respect the Sinhalese accord to elders, especially those who have accomplished great feats such as this dramatist has.

The two of them have a near 10-minute conversation which leads me to explore the idea of an independent north focused facilitation of artists alongside entrepreneurs and those from different fields.

Kulandai continues much of the balanced conversation with me in Sinhala and repeats his love for the language.

“Mage mawbashawal dekak thiyanawa. Issarinma egena gaththe Demala bhashawai Sinhala bhashawai. Mata kalekin mehema Sinhala jathakaranna hambawune nehe lama awadiyata passé. (There are two mother languages for me – Sinhala and Tamil which I learnt but I did not get many chances to speak it after my childhood days,” he states. He then goes on to explain and act out the voicing of varying words of the same meaning. One example is the word Daruwa as opposed to Lamaya. Said in different tones with accompanying gestures, he demonstrates that the word Daruwa can denote different meanings.

“My Tamil was a bit different to the Tamil being spoken in Jaffna and I was laughed at in the first few days in school. After I did my Advanced level from Jaffna Hindu College, I was loitering around at home when a cousin who was going to India for higher studies announced his visit to my mother and she saw to it that I did not waste any more time and that I too followed him.

I specialised in Economics, Politics and History in the BA from Madras University and later got admission to Bangalore Mysore University which was an affiliated college. I returned in my mid- twenties for what was to be a lifetime teaching career in Jaffna. I taught for 22 years at St. Joseph’s College.

“It is only at the age of 45 that I formally learnt drama. Some of my Jaffna friends told me about a diploma program being held in Colombo in 1976 and I enrolled. I was the only Tamil student. The course was taught by Sri Lanka’s foremost dramatists at the time; Dhamma Jagoda, Dharmasiri Bandaranayake, Henry Jayasena, Ernest MacIntyre, Solomon Fonseka and from the north, Prof. K. Sivathamby.

|

“What we learnt bordered on the art of the expressive that is a cross between psychology, poetry and theatre alongside other connected disciplines such as mind control, voice modulation and history,” says Kulandai who does not claim to be spiritual but recalls an incident that in a meditation oriented session conducted by Dhamma Jagoda which had students bringing a lighted candle up to their nostril repeatedly and which only Kulandai should do to achieve a stance like state which had his consciousness reaching an acute peak.

“This was one of the very first lessons taken by Dhamma Jagoda and I heard him ask the others as to who I was. I felt all the sounds around me and even my nostrils burning but at the same time I did not feel these sensations in a manner that would curb my concentration,” he states.

Asked how he sees drama being used as a catharsis, he speaks of how emotional he gets when he used to write some of his plays, most of which are full of poetic compositions.

“Tears used to flow from my eyes when I used to compose my plays. Another phenomenon was that I used to get eczema attacks.”

Professors of psychiatry such as Daya Somasundaram and Dr. S. Sivayohan have often got advice from Kulandai on working with those who have been negatively affected by the conflict, to use expressive theatre for trauma healing.

“Theatre is a counsellor by itself. It heals and it connects.” These are some of the words of wisdom that I hear as I leave his house and the image of him watering his plants in the spacious garden full of trees grown by his daughter on her vacation in Jaffna. He today does not write but looks after his ailing wife.

“I have written enough now. I don’t write anymore. I live among trees and do my duty by my wife,” he states.

Meeting him is a rare privilege of meeting a truly spiritual person who never uses the term to describe himself and brushes aside any link to being ‘artistic.’ His narration about himself and his theatre-based mission of nearly five decades is done in a down to earth manner and is a teacher of the concept of unaffected humility. As I bid goodbye to him I do so with the promise of meeting him again in mid-February.