Saturday Feb 14, 2026

Saturday Feb 14, 2026

Saturday, 25 January 2025 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

|

|

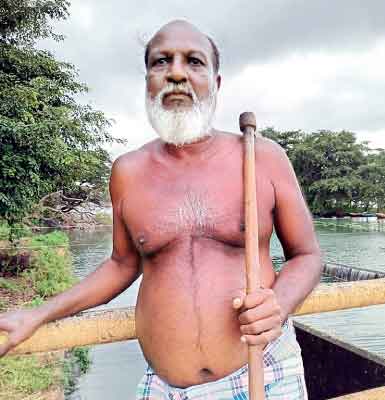

| Uru Warige Loku Bandila Aththo |

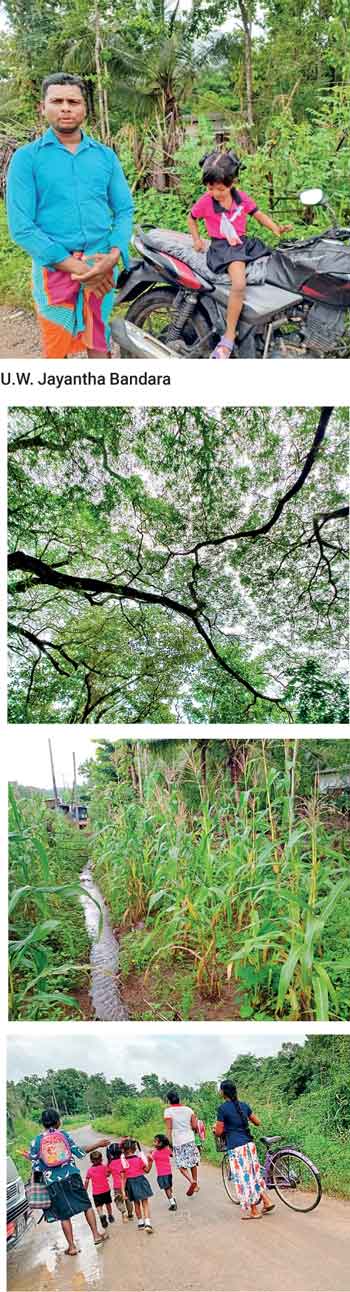

Aadi Vaasis of older generations in Henanigala |

Villagers of Henanigala

Villagers of Henanigala engaged in the brick industry

All of us now have clinic books. Every household has them almost for every family member. If someone is over 30 years old, they are sick. In some homes even the children suffer from chronic diseases. Every week we go to the big hospital close to Dehiathakandiya. We have every conceivable non communicable disease such as diabetes, cancer, kidney failure, arthritis, osteoporosis, water retention in the knees, asthma, wheezing, and constant headaches – Loku Bandila Aththo

By Surya Vishwa

By Surya Vishwa

When what is envisaged to be ‘development’ ends up as a sickening nightmare, there are no witnesses.

Uru Warige Loku Bandila Aththo is amongst the oldest in his village. He is now aged around 75 years, having settled down to a life totally alien to his ancestors in 1982. This was when the then Sri Lankan Government introduced the Mahaweli development scheme purportedly to usher in agrarian prosperity. Believing at the time that the leaders of the country knew what was best for his community, Loku Bandila Aththo arrived in Henanigala which was, prior to 1980, part of the expanse of the general wilderness in this locale. Nearly one hundred families of Sri Lanka’s Aadi Vaasi (Ancient People) moved from Kandegangwila, an area closer to Dambana and hoped for a better life, especially for their offspring. Some changed their names to match Sinhala names.

Today, over three decades later, the number of families in Henanigala have multiplied to a total of around 600 but they have a sorry story to tell.

“All of us now have clinic books. Every household has them almost for every family member. If someone is over 30 years old, they are sick. In some homes even the children suffer from chronic diseases. Every week we go to the big hospital close to Dehiathakandiya. We have every conceivable non communicable disease such as diabetes, cancer, kidney failure, arthritis, osteoporosis, water retention in the knees, asthma, wheezing, and constant headaches,” explains Loku Bandila Aththo.

Poisoning of water through chemical based fertiliser, pesticide and weedicide

He himself is a very sick man with complicated kidney issues. Among the commonest most ailments are kidney failure, diabetes, asthma and migraine that they link with the poisoning of water through the consistent use of chemical based fertiliser, pesticide and weedicide over the past years. Two water filters had been set up in the Henanigala school few years back through a personal donation but its impact cannot be measured in the face of the seriousness of the problem.

Uru Warige Loku Bandila Aththo heaves a helpless sigh and unlocks his sorrows.

“Who comes to ask us how we are faring? Who has compassion for us? Who do we tell our problems to? I took my clinic book and went to the hospital just yesterday. We were never a weak people. My grandparents lived to be over 100 years. Previously we have never ever heard of the illnesses that we are cursed with today.”

As he explains, for his ancestors life and death were seen as two interconnected dimensions. They lived knowing that they the hunters would one day be hunted by death. It could come from a tussle with a wild animal or from any general tribulations of living with the forest but these incidents were rare. They were part and parcel of the forest. They were the caretakers of it, hunted from it, was prepared for the risks that came with their lifestyle and considered the forest their school, their college and their university. Yes, their grandparents and parents died but only of old age and never from the multifarious sicknesses that plague modernity.

Barred from the forest

“We lived with the forest, ate of it and hunted as necessary. But today we are helpless. We are barred from the forest. We are sick. We were hunters. But now we are cultivators. We cultivate with hybrid seeds as we were told to when we were sent here with the creation of this village. We use synthetic fertiliser and weedicide which we know are not good for either us or the soil. But what are we to do?” asks Loku Bandila Aththo.

“The soil too is like our bodies and it has now got completely addicted to the imported fertiliser, weedicide and pesticide. Our ancestry was not linked to farming but we know that heirloom rice varieties of this land were adaptable and required only the nourishment that was of nature – the leaves that fell naturally from surrounding trees made the earth rich and it fed the soil. There were wild rice varieties that could be grown in different terrain. We knew all these.”

“Today we put to soil artificially produced rice grains and naturally we have to use the industrialised fertiliser. Although we had many leaf varieties which our ancestors knew how to use to ward off insects and contain weeds, this expertise is lost to us today,” he explains.

How was it before they arrived here?

“The Veddha clans of this country exist today in areas such as Dambana, Rathugala, Dimbulagala, Nilgala, and Pollebeddha. Our ancestries could be traced through names such as Uru Warige and Thala Warige. These were names that are associated with the natural world. But the names we give nowadays for our children and grandchildren are Sinhala names because if we do not do that, they would have problems assimilating with other young people in the country. They go to schools where the curricula is the same as the rest of the country. Our Aadi Vaasi language is unique but our children know only a smattering of it. It is not taught in the brick schools they go to nowadays.

“The only school our ancestors knew was the forest and since we do not want them to forget our sacred language we talk to them in it at home. But their lives and their dreams of the future are dominated by this so called civilised world that see us as primitive. Maybe the young children of our ancestry are ashamed of their elders. Perhaps some of them want to move away from these areas and identify themselves with the big cities.”

The sadness in the face of Loku Bandila Aththo is evident in his voice.

Freedom was our key asset

“Freedom was our key asset. We were free to be in our home the forest and we lived with the animals and hunted as necessary but never for greed. The forest never was harmed by us. But now we have no livelihood. When we were sent here in the 1980s it was as if taking a fish out of water – how can you ask a fish to survive and live in a place it cannot breathe? This is almost the same for us. The modern law of this country forbids us to hunt. If we do so it is illegal. In 10 years or so the Aadi Vaasi identity will be lost. There will not be anybody in the younger generations who have an understanding of the forest, its plants of medicinal value, the Aadi Vaasi language, the verses that our ancestors composed and sang or any of the vast realm of knowledge and belief system connected to the universe that was our heritage,” he laments.

Many of the Aadi Vaasi community members have inter married with Sinhalese. D.M. Gunatilleke, in his late fifties, is the offspring of such a liaison where his father is Sinhalese and his mother an Aadi Vaasi – Uru Warige Somawathie.

“I live in Halmilla in Henanigala. I am not very old but I am a very sick man. Previously I engaged in cultivation. Now I have a disease where my muscles are wasting and my weight has decreased. I have no energy to engage in any farming or livelihood generating activity. What do you call such a life? I feel I am in a prison in my old body which is made useless in a manner that my ancient ancestors would have been ashamed and aghast at.”

The common form of income generation is growing paddy, corn and vegetables but some families also carry out clay brick manufacturing which have some demand from areas such as Kandy or Colombo for their rustic look and reasonable cost.

Some of the residents of Henanigala have their own land – mostly around one acre each but many don’t. A large number of residents wake up each morning wondering where they could get some labour work. Some go to other adjoining villages to look for labour work in cultivation fields.

Henanigala seems a forgotten village with little to interest local or international visitors which is the opposite of Dambana, the apex centre of the Aadi Vaasis which gets large numbers of sojourners especially on public holidays where the atmosphere is strident with a picnic type of vibe where many cap, hat and stylish clothing wearing, sun glass donning city dwellers keen for an ‘experience’ throng the place. While the Aadi Vaasi community in Dambana have over the years transformed into sales people where they sell things such as bees honey, herbal oils, decorative items made from different seeds, different kinds of knives and perform forest linked dance rituals for audiences for a fee, in Henanigala the situation is totally different. There is nothing in the village that can symbolise that the forefathers of Henanigala engaged directly with the sun, earth, sky and the universe.

While the commercialisation that one sees in Dambana is an outcome of the metamorphosis we have forced on this community, so is the modern agrarian system in Henanigala that on the surface looks lush with vast green paddy fields.

Many diseases are linked to farming

“We know that our many diseases are linked to the farming we do where we use none of the ancient methods. We are people of the forest but our ancestors also spoke to the earth as they would do to a child and planted that which they would need for their basic consumption. This was you can say close to a kind of agrarian forestry we had designed when we were somewhat influenced by the villagers. But this is not how it is today. Today the world of industry have ridden over us. What are we to do? How can we turn back the clock?” asks 37-year-old U.W. Jayantha Bandara, better known as Buddhika in the village.

“Even as a child I recall that my parents lived a different life but I grew up with Rasyinika Pohora (synthetic fertiliser) and hybrid rice varieties. In this village or areas around none of the ancient traditional rice varieties are grown. The way we do the paddy cultivation now, here we need well over 300 kilos of chemical fertiliser alongside much weedicide and pesticide,” he adds. His father was Uruwarige Tissa who grew up in the forested area of Kandegangwala where there were five decades ago around 70 families, all of whom migrated to Henanigala. Today, the best Jayantha could hope for, is that his three-year-old daughter becomes ‘educated.’

For most children in Henanigala the ultimate dream is to be a teacher or to join the Navy, Army or Police.

Eleven-year-old Maduka is the grandchild of Uru Warige Loku Bandila Aththo and he does his schooling at the Henanigala Vidyalaya.

“I want to join the Navy. I will do so soon, in a few years,” he declares. He has a penchant for Mathematics and English. Of the language of his forefathers, he knows only a few words. He is aware that in his father’s language, a school is known as ‘kuru kuru gachana rukul pojja,’ that a coconut tree is described as ‘Kiri gejja thibena rukang pojja,’ and that a dog is identified as ‘kukkila aththo.’ He is too young to worry about the fact that this historical language which developed amongst the first people of this island is now becoming extinct.

Joblessness is what any ‘educated’ youth of Aadi Vaasi heritage could expect. There is no mechanism set in place to link the ancient with the modern in a manner that safeguards the dignity and self-respect that the Aadi Vaasis once proudly nurtured as they did their home, the forest. Yet the older generations of Henanigala, ridden as they are with hopelessness, try and bolster their willpower to survive in a world hostile to them, by recalling that they carry the lineage not only of their clans but of this nation itself.

Note: The Harmony Page is pleased to inform that it has initiated a program to conserve the language of Sri Lanka’s Aadi Vaasis and pass this knowledge onto younger generations of Sri Lankans as a whole. The Harmony Page will also publish in the weeks to come, a set of policy ideation based on our media research in Dambana and Henanigala. Based on extensive field research, we will provide recommendations on how heritage communities could be prosperous in the true sense of the word and thereby contribute to the national economy while strengthening the cultural identity and heritage of Sri Lanka.