Tuesday Mar 10, 2026

Tuesday Mar 10, 2026

Saturday, 31 August 2024 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

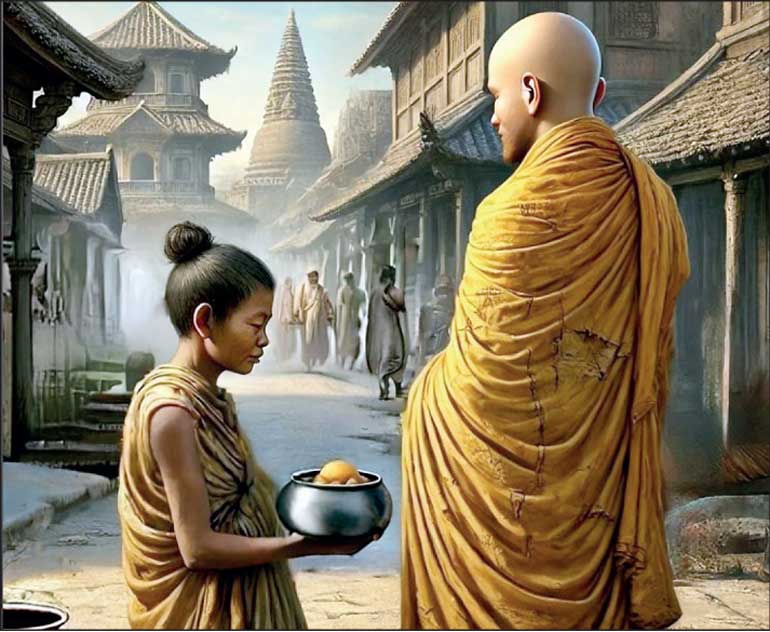

The story of Modakadāyikā Theri, a water carrier, who found

liberation, holds profound relevance even today

By Don de Silva

She wasn’t a princess or a queen. Nor was she from an aristocratic background. She had no riches to give. Books have not been written about her. She has not been featured in social media. She was from a humble background.

Yet her name is right there in the Tipițaka, in the teachings of the Buddha Dhamma. Within this vast body of texts, she has just seven sentences in the Apadānapāḷi, Tales of Past Deeds, a section within the Khuddaka Nikāya. It contains biographical stories and verses that recount the past deeds and virtues of the Buddha’s disciples, both monks and nuns.

Her name was Modakadāyikā, she was a potter’s servant, a water carrier, probably a bondservant. Yet, her story has come down generation to generation as part of the Tipițaka.

In the bustling city of Bandhumatī in ancient India, she carried her load, back-breaking work, fetching water each day for a potter. She says:

“Nagare bandhumatiyā, kumbhadāsī ahosahaṃ;

Mama bhāgaṃ gahetvāna, gacchaṃ udakahārikā.”

In the city of Bandhumatī, I was a potter’s servant; carrying my load, I went, fetching water.

One day, on the road, Modakādayikā saw a serene monk with a tranquil mind. With a delighted and joyful heart, she offered him three sweetmeats. She did not have riches to give, but she gave what she had, from her heart. Through that good deed, her intention and resolve, she avoided the lower realms for ninety-one eons. She continues:

“Panthamhi samaṇaṃ disvā, santacittaṃ samāhataṃ;

Pasannacittā sumanā, modake tīṇidāsahaṃ.”

On the road, I saw a mendicant with a serene and tranquil mind; with a delighted and joyful mind, I offered three sweetmeats.

“Tena kammena sukatena, cetanāpaṇidhīhi ca;

Ekanavutikappāni, vinipātaṃ nagacchahaṃ.”

Through that good deed, and through my intention and resolve, for ninety-one eons, I did not go to the lower realms.

“Sampatti taṃ karitvāna, sabbaṃ anubhaviṃ ahaṃ;

Modake tīṇi datvāna, pattāhaṃ acalaṃ padaṃ.”

Having achieved that prosperity, I experienced all [good fortune]; by offering three sweetmeats, I attained the immovable state [of enlightenment].

“Kilesā jhāpitā mayhaṃ…pe… viharāmi anāsavā.”

My defilements are burnt out...pe... I live without taints.

“Svāgataṃ vata me āsi…pe… kataṃ buddhassa sāsanaṃ.”

Welcome indeed was it to me...pe... The Buddha’s teaching has been done.

“Paṭisambhidā catasso…pe… kataṃ buddhassa sāsanaṃ”.

The four analytical knowledges...pe... The Buddha’s teaching has been done.

“Itthaṃ sudaṃ moda kadāyikā bhikkhunī imā gāthāyo abhāsitthāti.”

Thus, it is said, the nun Modakadāyikā spoke these verses.

This is the third account of the Elder Nun Modakadāyikā.

The name “Modakadāyikā” can be understood by breaking it down into two parts: Modaka: This term refers to “round sweetmeats,” which are traditional sweet treats often offered in various cultural and religious contexts. Dāyikā: This term means “giver” or “donor.”

Therefore, “Modakadāyikā” translates to “the giver of round sweetmeats.”

Its relevance to today’s world

Let’s take this remarkable story in the Tipițaka and see its relevance to today’s world. 2,500 years later the situation has not changed much. This principle is particularly relevant today, as millions of people around the world, especially women and girls, continue to carry the burden of water collection and household responsibilities.

The latest publication by UNICEF and WHO on drinking water, sanitation, and hygiene reveals stark realities: 1.8 billion people collect drinking water from sources located off premises. In seven out of ten households, women and girls are primarily responsible for water collection. In almost all countries with comparable data, the burden of water carriage remains significantly heavier for women and girls than for men and boys.

A BBC article on water carriers in India describes how a water carrier spends four-to-five hours every day travelling back and forth from nearest reliable water sources to fill pots.

The story of Modakadāyikā Theri, a water carrier, who found liberation, holds profound relevance even today. Her story reminds us that greatness is not always about grand gestures. Her simple act of giving just three sweetmeats, a small but heartfelt offering, had a lasting impact. Through the teachings of the Buddha Dhamma, anyone irrespective of social status can find empowerment and change.

By giving away her sustenance, she demonstrated an extraordinary level of generosity and selflessness. This act was not just a simple gesture; it was a profound sacrifice, showing the depth of her compassion and the purity of her intentions.

True generosity comes from the heart

The story emphasises that true generosity comes from the heart, not from the abundance of one’s possessions. Modakadāyikā did not have riches to give, but she gave what she had sincere intention.

The name “Modakadāyikā” – the giver of sweetmeats – lives on, as evidence to the profound simplicity and power of a generous heart. You don’t have to give riches; you only need to give from your heart. It is wonderful to note the rich array of stories that are contained with the Tipițaka.

Source:

Find the narrative of Modakadāyikā Theri from the Tipițaka App:

Suttapiṭaka: The Basket of Discourses Khuddaka Nikāya: The Collection of Minor Texts Apadāna: Stories or Tales of Past Deeds Ekūposathikavagga: The Chapter of One Who Observes Uposatha Modakadāyikātherīapadāna: The Story of the Elder Modakadāyikā

(The writer is a former director of the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) who links traditional knowledge, environmental sciences and spiritual/cultural heritage. Don de Silva is Buddhist Counsellor and Mentor at several UK universities. He is also involved with Sri Lankan universities. He researches the Buddhism based Intangible Cultural Heritage and its relevance to sustainability, peace, unity, abundance and communication systems.)