Friday Feb 20, 2026

Friday Feb 20, 2026

Saturday, 4 June 2022 00:26 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Dr. Mohamed Safiullah Munsoor

One of the key points in terms of the Prophet Muhammad and his leadership including his succession forms the point of departure between the sunni and shia. Nasr (2007) points out that “…to Shi’ism, in addition to the power of prophecy in the sense of bringing a divine law (nubuwwah and risala), the Prophet of Islam, like any other Prophet before him, had the power of spiritual guidance and initiation (wilaya), which is transmitted through Fatimah to Ali and through him to all the Imams”.

One of the key points in terms of the Prophet Muhammad and his leadership including his succession forms the point of departure between the sunni and shia. Nasr (2007) points out that “…to Shi’ism, in addition to the power of prophecy in the sense of bringing a divine law (nubuwwah and risala), the Prophet of Islam, like any other Prophet before him, had the power of spiritual guidance and initiation (wilaya), which is transmitted through Fatimah to Ali and through him to all the Imams”.

This link is very strong within the Shi’a tradition, where for example, Amir-Moezzi (p 135 in Newman, 2014) highlights that, where according to traditions in which the Prophet had said that he was created with Ali before the world from the same light. In this further reinforced, where the Imami tradition reconceptualises the Prophet’s ascension to heaven (mihraj) within a Shi’a context, where he was made aware that Ali had been designed as his successor.

In the above light and according to Shi’ism this is evidenced by the famous hadith-i kisa (the tradition of the garment), where the Prophet covered his household with a cloak that included his daughter Fatimah, his son-in-law Ali, together with their children Hasan and Husayn and prayed for them. After the Prophet the cloak was handed over to Ali and then it continued to the Imams as per the Shi’a tradition. This in effect constituted, the cloak as an esoteric symbolism of the transmission of spiritual guidance and initiation into the path by the family of the Prophet (Nasr, 2007). Apart from this, who else constitute the family of the Prophet is a question of debate.

So in effect, in Shi’ism one has to follow the Imams who are part of the long lineage, which differs within the sunni tradition, where one can follow a Sheikh, who is a spiritual leader, who may or may not necessarily be in the lineage of the Prophet and his family. The lineage or ‘silsila’ where there is a long line of previous Sheikhs where the spiritual transmission is made nevertheless does exist in the sunni inward tradition. Apart from this there are many similarities between Shi’ism and the sunni tradition especially within the light of ‘tassawwuf’ or the inward science of Islam, which is taken up in another discussion.

One key reason for examining spiritually-oriented leadership is that the leaders have been found to be more effective and transformational in nature than leadership in other settings (Druskat in Reave 2005). Motivation, which is spiritually-oriented and faith-based is identified as a ‘distinguished variable’, which is the cause of much of the transformational leadership (Reave 2005). The sense of commitment of these types of leaders are said to be derived from their ‘own conscience and internalised values’ derived from a spiritual sense of connectivity with a higher power (Bass in Reave 2005). As seen in the discussions above, the best illustration has been the life of Prophet Muhammad, who was able to transform the people from their state of ignorance to a more enlightened state.

In Ibn Khaldun’s articulation, work or craft is seen as a metaphor, whereby one personally grows both his/her social roles and technical skills (Kriger and Send 2005). Within the Islamic context, worship and services are intrinsically linked, where as we have seen in the example of the Prophet, that good works and right conduct are seen as that which shape the soul or the inner self towards good and leads to better connectivity with God.

The rapidly expanding societies of the world, with its global outreach have called for a re-examination of organisational structure and its roles and responsibilities. In this sense, a more holistic leadership is called for, which “integrates the four fundamental arenas that define the essence of human existence – the body (physical), mind (logical/rational), heart (emotions, feelings), and spirit” (Moxley cited in Fry 2003).

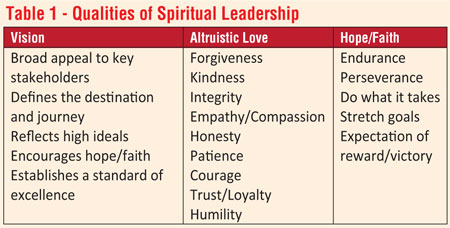

It is argued that spiritual leadership is necessary for the transformation, as well as the success of learning organisations, and in this light, “spiritual leadership taps into the fundamental needs to both leader and follower for spiritual survival so they become more organisationally committed and productive” (Fry 2003). In this context, spiritual leadership is defined as “comprising the values, attitudes, and behaviours that are necessary to intrinsically motivate one’s self and others so that they have a sense of spiritual survival through calling and membership” (Fry 2003). The qualities that are often associated with spiritual leadership that are outlined in Table 1, which subsumes the characteristics of the Prophet.