Tuesday Feb 24, 2026

Tuesday Feb 24, 2026

Saturday, 12 November 2022 00:12 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

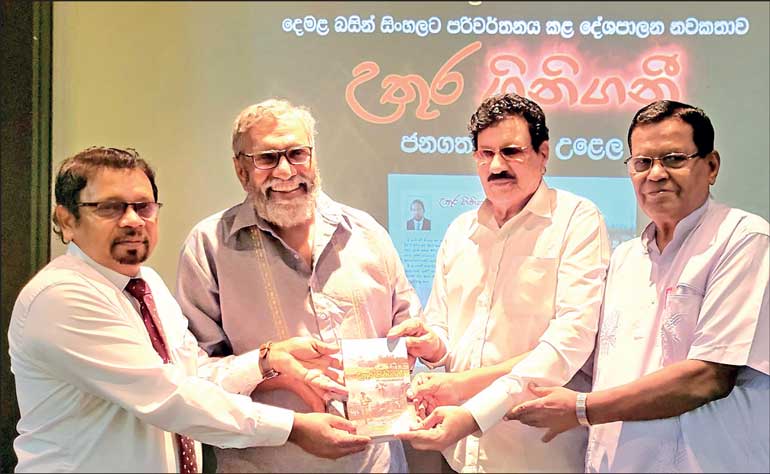

From left: Translator of the book Hemachandra Pathirana, former Elections Commissioner Mahinda Deshapriya, Tower Hall Foundation Director Hasim Umar, and the author T. Gnanasekeran

Tamil and Sinhala cultural performance of dance and song held at the launch

By Surya Vishwa

Words, whether written or spoken, are but images of a human being’s innermost consciousness. These thought images bind us to our minds and through this bond connect us to each other. Written word literature consists of the creative consciousness of the human being expressed in prose and which conjures up sadness or happiness.

Words, whether written or spoken, are but images of a human being’s innermost consciousness. These thought images bind us to our minds and through this bond connect us to each other. Written word literature consists of the creative consciousness of the human being expressed in prose and which conjures up sadness or happiness.

Scholars of mass communication as well as global literature especially know that history was shaped and policies changed for the better because of the word moulded empathetically and creatively. The word that weaves one to another; to place one human being in the shoes of another’s predicament by enabling him to understand what it would be to live another’s reality; to feel what the other has felt based on the circumstances the other has faced.

From the renaissance, to industrialisation, the civil rights movement, the abolition of slavery and the feminist movement – the commonality remains that the creative word has created wars for justice and brought about peace, changing hearts, minds and policies. The novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin by Harriet Beecher Stowe, the poetry of Langston Hughes and the tale Oliver Twist by Charles Dickens are a few examples of how the power of the literary word changed stoic hearts and oppressive laws.

Sri Lanka has spent close to half of its post-colonial existence in the backdrop of a conflict described differently, depending on the human experience and form of suffering or indoctrinated and fixed views/biases faced by the narrator.

Thirteen years after the end of a 30-year-old saga of death, mayhem and destruction of a national economy and people, the creative expression remains a way this island nation could communicate, within its people, the different viewpoints from different angles of thought. Healing from injustice and trauma is a very long road. Possibly countries such as Britain, America and Germany are still to fully mentally heal from the oppression/destruction caused to the forcefully occupied colonial states such as India and Sri Lanka, and yet to come to terms with the unprecedented human rights violations of Native Americans, Africans, the Jews and the Iraqis to name a few who have suffered abominably due to unjust policies.

We recently saw a Sri Lankan winning the Booker prize for taking a particular Sri Lanka related viewpoint to the world highlighting particular cases of violations of human rights.

In this backdrop, a Sri Lankan Tamil of Northern origin who had spent over seven decades of his life in different  parts of the country, especially the tea plantation areas as a medical doctor had the launch of the Sinhala version of his book on the Lankan ethnic strife, set in 1984, the early part of the separatist terror or struggle as interpretation merits. The year 1984 marks a year after the 1983 anti-Tamil riots.

parts of the country, especially the tea plantation areas as a medical doctor had the launch of the Sinhala version of his book on the Lankan ethnic strife, set in 1984, the early part of the separatist terror or struggle as interpretation merits. The year 1984 marks a year after the 1983 anti-Tamil riots.

Titled in Sinhala as ‘Uthura Ginigani’ (North Burns), and in English as the Volcano, the book was originally titled in Tamil as Erimalai (Volcano). The book, authored by T. Gnanasekeran and translated to Sinhala by Hemachandra Pathirana, was launched this week at the Bank of Ceylon auditorium premises in Fort under the Sinhala title of Uthura Ginigani.

The book published by Godage Publishers is currently available in Tamil, English and Sinhala, in their bookshops island-wide. The plot of the story commences with a Lankan Tamil medical doctor, his wife and an injured member or the LTTE and the different people who get involved into the story which begins when the injured LTTE member coerces the fearful and reluctant Tamil doctor to carry out treatment.

The injury of the LTTE guerrilla occurs when he and a few others launch a bank robbery in Sri Lanka’s north and the said doctor’s wife calls the Sri Lankan police established by 1984 in the north to quell the rising unrest. After one of the culprits gets injured in the clash with the police the Tamil doctor is afraid of unnecessary complications he would face with the police if he carries out the required medical treatment. The reluctance of the doctor to get involved in treating the guerrilla summarises the predicament that many physicians at the time faced.

The Sinhala involvement in the story occurs when a south-based academic and his family who are friends of the doctor arrives in the north and thereby is exposed to the harsh realities that the Tamils of the district are just beginning to recognise will be their everyday fate.

The plot becomes humanistic with the involvement of the perennial saga of love that occurs even in the worst of manmade hells of this earth. One of the female family members of the south-based Sinhala family – friends of Dr. Mahesan’s kith and kin – comes on a short visit to the north, unable to come to terms that the base for ‘large scale hostilities’ has actually started.’ A romance soon develops between the said female and Dr. Mahesan’s brother (who is unable to justify to his mind the separatist ‘cause’ of the LTTE) and although the story does not give a definitive conclusion as to what occurs at the end with regard to their commitment to each other – the couple remains adamant to marry each other even if the two sides oppose.

With the involvement of the romance and the multifarious positives and negatives of how the Tamil-Sinhala family social dynamics play out in the respective communities, there is well-crafted analysis that comes naturally within the story. This juxtaposition stands starkly innocent against what the country generally known as the politicisation of a rift that occurred after the divide and rule policy of the colonial rulers.

The truth is that when one attempts to write about the 30 years of battlefield woes of this country, the writer if he or she is a journalist and depending on what type of publication owned by which kind of management (applicable to both local and international publications/agencies), would have to use different terms to describe the separatists – either as ‘terrorists,’ ‘freedom fighters,’ ‘guerrillas,’ or ‘LTTE cadres.’

In turn the government military will also be described in different terms – as the ‘military,’ the ‘Sinhala army,’ or the ‘State security personnel’ to name a few. In these terms are lost the vicissitudes of human connection. The struggles between the bullet, the landmine and the terrain of the mind and the oasis of the human heart is often left to salvage whatever entrails left of empathy and understanding a perspective different to one’s own. But few writers can achieve this. In this aspect Gnanasekeran has won the day.

The success of the Sinhala book and the reality of it being published for the Southern reader is because of the yeoman service done by the translator, Hemachandra Pathirana, who possesses an MA in Tamil language, a very rare feat for a Sinhalese. He has not kept his ability hidden and over the past 15 years has translated around 15 books into Sinhala and Tamil respectively. This is in addition to him being an efficient teacher of Tamil and Sinhalese.

In the time when modern education is chained to the iron bars of memorisation and rote learning, the nurturing of what we consider to be important in all human matters – emotional intelligence remains a dire need in a country such as this where mayhem has become the normal psyche of citizens.

Yet in the book ‘Uthura Gini Ganu’ what is seen is an attempt to give the Tamil perspective, if that term could be used in a generic sense while at the same time, allowing the characters of the story, Tamils and Sinhalese holding directly opposing sentiments to surface in the everyday conversations. Justifying of the military or government action or justifying the rise of the LTTE or being staunchly opposed to terror being used as a vehicle to win the rights of the Tamil people are few of the differing opinions expressed.

Hemachandra, with whom this writer has discussed the many issues of this country’s ‘language’ and related issues possesses a beautiful mind that is not corrupted by biases. He stands with the many Sinhalese and Tamils of this land who do not aim to be kingmakers by rabble rousing that is so easily achieved to perfection when ‘criminalising’ the other based merely on that ‘otherness’ and often selling it on the digital pavement of social media or even in literature.

Says Hemachandra in his message in the book, “It is the skill of Gnanasekeran to have used very realistic characters in his story who are both Sinhalese and Tamils who hold a myriad of opinions that actually are spread out in Lankan society in seeking to analyse and understand the origin of what we call the ethnic strife of this country which have separated human beings on lines of race, religion and language.”

In a recent interview with this writer (the detailed version of which will be published soon) Hemachandra pointed out that he is promoting trilingual education for the explicit reason of wanting to do more translations of literary works across the language divide in Sri Lanka.

Also holding an MA in the English language he believes that language proficiency of all Sri Lankans in Sinhala, Tamil and English would greatly contribute to national reconciliation – especially literacy in the written word.

“If I am able to look at the pre and post war dialogue in an open minded way it is because I have read many and translated several of the books that talk of varied discourses in relation to the ‘ethnic identity’ and integrated ‘politics.’

Hemachandra and I both discuss and agree that mortal human beings always function with some kind of conscious or unconscious mental bias based on the circumstances of life experience. Hence one may view the episodes of the book at times being diversely favourable to some entity or argument. This book could be hailed as offering the Sinhalese what could be called ‘the Tamil sentiment’ while understanding that this sentiment cannot be likened to one that emerges in a cookie cutter framework.

This book, which is a novel, accurately displays the salient fact that one cannot call anything as the absolute ‘Sinhala opinion’ or ‘Tamil opinion’ in how the blame and praise is divided across the putrid landscape of Sri Lanka’s political mess. The political mess that was the fertiliser of the poisonous seed labelled and advertised as the ‘ethnic conflict.’

The inane policy decisions of standardisation initiated in 1971 (and annulled in 1977) that impacted the university admittance and thereby the career advancement of the Tamils of Sri Lanka, known then, as is now, to be a community known for its academic diligence, is cited as being one of the foundations that made Sri Lankan Tamils to be ostracised and leave their country of birth.

The book sensitively conveys to any non-biased reader how a citizen can be made to feel let down or hurt by certain policies.

The author, Dr. Gnanasekeran who had lived his childhood in a time when the average Sri Lankan would have scoffed if told that this land would be drowned in blood of the Sinhalese, Tamils and Muslims, clearly points out in the preface of the publication that what Tamils felt to be initially a justified stance by a segment of its youth (in the early1970s) could not support the blatant terror that ensued thereafter.

The author does not mention the fact (that emerged in a documentary film by a Tamil film maker about 4 years ago) that the LTTE ended up killing a similar number as those killed on the battleground.

The author Gnanasekeran, hailing from the village of Punnalekattuwan in the Jaffna districts draws on what he has experienced in everyday conversations and situations in 1984, when the LTTE’s terrorism (also could be referred to as the ‘cause’ had just begun). The Sinhala language version of the book being launched nearly three decades later gives us some mental space to contemplate upon the cancer of ethnic strife that was injected under our eyes under different brands of purported patriotism.

In the story plot the main character Dr. Mahesan’s brother remains staunchly against the LTTE and their brand of ‘struggle’ which allows the Southern Sinhala reader to understand the two divergent Tamil views regarding the LTTE.

This page would soon carry a discussion with the author on the birth of the story and its incubation period before it faced the world as books in all three languages. The detailed review of the English version of the book will also be published concurrently, the aim being to create inroads into understanding the many hair splitting arguments and interpretations with which we scorch our minds, the ashes of which could probably be measured as having equal weight in being the ‘correct’ argument – depending on the lenses with which you look.

To sum up, the reality is that topics of ‘war atrocities,’ particularly if it is those that are assumed to be from the government military side, are stuff that could be intensely marketed internationally under the label of ‘human rights.’ Such writings may get one even to the echelons of the world literary circuit but it may do very little in bringing about the desperately needed understanding and dialogue between communities living in this nation.

In the context of peacebuilding the highlighting of negative factors that exist in any society may only give energy to that negativity and wipe away the good that occurs even in the worst situation that is the actual lamp that will light the path to illumination.

(The Harmony page is committed to the mission of promoting that which is beautiful, magnanimous and courageous and we hope to continue further on the interview with Dr. T. Gnanasekeran and Hemachandra Pathirana as well as excerpts of the English version of the book as we contribute to the national need of unity, understanding and reconciliation.)