Wednesday Feb 25, 2026

Wednesday Feb 25, 2026

Wednesday, 11 March 2020 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Dr. Thulitha Wickrama, Dr. K.A.S. Wickrama, Dr. Sukunan Gunasingham, Sivaguru Thanigaseelan and Saranya Sathiyavasan

Mosquito-borne diseases such as dengue, malaria, yellow fever and filaria were responsible for more human death in the last there to four centuries, than all other causes combined. Most of the prevention and control programs implemented during the last century were effective in preventing the transmission of these diseases by eliminating the principal epidemic mosquito virus.

These programs focused on removing mosquito breeding sites through environmental hygiene along with the use of chemical insecticides. However, it appears that the effectiveness of prevention programs has diminished, and mosquito-borne diseases have begun to re-emerge in developing countries, in the last few decades.

Particularly, the emergence of dengue caused by mosquito virus (aegypti) was significant in many countries in Central America, Africa and Asia. Increased disease transmission and frequency of epidemics caused by multiple virus serotypes have contributed to an increase in the movement of dengue viruses through mosquito into these regions. In these regions, dengue incidence increased dramatically, expanding distribution of the virus.

In some countries, dengue has become a major epidemic and the second most important tropical disease (after malaria). The economic and public health impact of dengue has severe negative consequences for economic and social development in the developing world.

However, less is known about the failure of existing prevention and control programs that may be partly responsible for the emergence of mosquito-borne diseases, particularly dengue. A few studies have pointed out that heavy reliance on chemicals and inadequate focus on psychosocial risk and resources of the residents or communities may have contributed to the ineffectiveness of these programs. Prevention research has shown that social, family and individual characteristics contribute to the effectiveness of health preventive activities. We will briefly discuss these contributing factors in the paragraphs that follow.

Physical and spatial context

Physical and spatial characteristics of the environment—including stagnant water bodies, unplanned development, rurality, dense vegetation, and polluted neighbourhoods— promote mosquito breeding sites. Additionally, social environmental characteristics such as within-house human/family density and within neighbourhood house density (congestion) may contribute to increased transmission of mosquito-borne viruses.

Social ecological context: family and community

Apart from physical environmental conditions, the social ecological perspective and community studies suggest that social functional context, particularly positive family and community characteristics, acts as an important resource for effective behavioural intervention and health promotion. This should also be true for mosquito-borne disease prevention and control activities. Familism, an overall measure of family functioning, is an important social-psychological resource necessary for family-level health-prevention activities to which family members collectively participate. Familism refers to a collectivist orientation rather than an orientation toward personal success.

Familism is reflected by multiple positive family characteristics, including communication, mutual support and care, cohesion and effective problem solving within the family. Family-level preventive activities may include maintaining a mosquito-protected home and yard, healthy and preventive family habits, rituals and traditions, as well as family control over individual risk behaviours. Further, family and relational theories contend that supportive family functioning may promote knowledge of and adoption of preventive behaviours by family members. Thus, we expect that Familism contributes to prevention of dengue directly through family-level preventive activities and indirectly through its influence on knowledge and preventive behaviours of family members.

According to the social ecological perspective, community characteristics also exert contextual influence on community residents as they live and function in the community—especially community collectivism, a community-level characteristic similar to Familism. Community collectivism, an overall indicator of community functioning, is reflected by community organisation, community knowledge, community support and participation, community cohesion and efficacy which are necessary for effective community-level prevention and health promotion activities. These community-level activities may include collective maintenance of a mosquito-protected community environment, community acts and programs that promote prevention and health (e.g., awareness programs), as well as social control over family and individual risk behaviours. Further, effective community organisations can acquire necessary health and preventive services for their communities. Thus, we expect that community collectivism contributes to prevention of dengue directly through community-level preventive activities and indirectly through its influence on preventive behaviours of families and residents. Furthermore, the physical environmental context in which a community is imbedded may influence its functioning. That is, physical and social isolation, generally reflected by its rurality, may negatively influence community-level preventive activities.

Individual characteristics

Consistent with cognitive-behavioural theories, individuals possess the most proximal resources and risks associated with illness, including dengue contraction. An individual’s knowledge about mosquito breeding, transmission and prevention serves as an effective individual resource associated with his/her preventive behaviour. A person who is knowledgeable is more likely to recognise the importance of dengue preventive behaviours and to believe that they can personally take actions to prevent disease contraction. Furthermore, psychological competency and motivation, which are essential for building individuals’ capacity to engage in dengue preventive health promoting behaviours, are associated with one’s knowledge. We expect that these individual characteristics, particularly individual knowledge and preventive behaviour (individual agency), may uniquely contribute to disease prevention. In addition, individual-level material resources reflected by his/her social markers such as income and education also contribute to individual agency. Thus, the first objective of the current study is to examine environmental, social, family and individual characteristics associated with dengue infection.

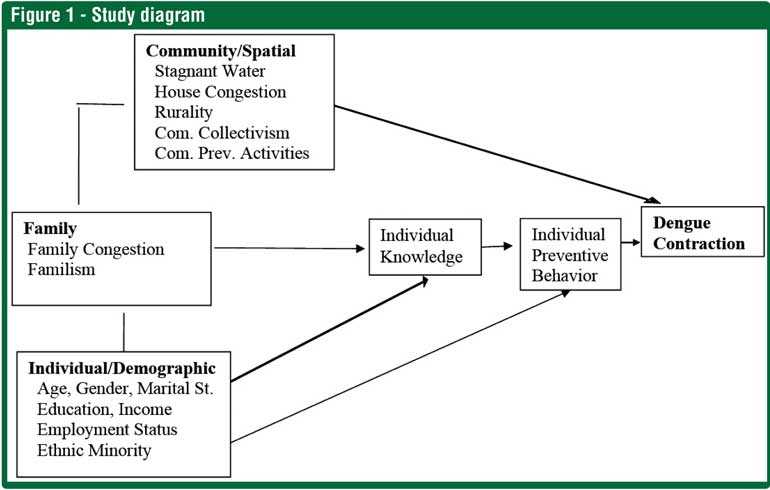

Further, these multilevel preventive factors may combine to influence disease prevention. As previously noted, social ecological research suggests that environmental, community and family influence on prevention partly operate through individual preventive behaviour. Also, community context may influence family characteristics producing a multi-level web of influences. Thus, the second objective of this study is to elucidate mechanisms through which environmental, social, family and individual factors may combine leading to dengue contraction. Figure 1 depicts our hypothesised model capturing these multilevel mechanisms, addressing our second objective.

The hypothesised multilevel model

Drawing from a combination of social ecological theory, relational and family theories and cognitive-behavioural theories, we have outlined our hypothesised model as shown in Figure 1. According to this model, we expect that environmental, community, family and individual characteristics uniquely influence dengue transmission. In addition, community and family characteristics influence the most proximal infectious risk/resources, individual knowledge and preventive behaviours.

The present study: Sri Lanka’s experience with dengue

The peak months of dengue coincides with monsoon times in Sri Lanka, when rainfall, and accompanying watery habitation sites for dengue carrying mosquitoes, is at its peak. The highest number of dengue cases were found in 15 districts in western, central, and eastern provinces which were most heavily affect by monsoon rains, with failures to clear rain-soaked garbage, pools of water, and other mosquito breeding grounds. Dengue virus serotype 2 (DENV-2) is still circulating with a significant frequency. Although the government has launched extensive prevention programs, it appears that these programs need to be more effective and extensive enough to control dengue contraction.

As in the case of other developing countries, little is known about the individual, family, community and cultural factors influencing dengue infection and prevention activities in Sri Lanka. This research deficiency is largely related to disadvantaged population groups. Thus, the specific purpose of this study was to bring an understanding of the individual, familial, and contextual risk and protective factors associated with dengue infection in Sri Lanka from a social epidemiological perspective. We expect that study findings will enhance the formulation and implementation of preventive strategies and programs not only in Sri Lanka but also in other developing countries.

Study design

Batticaloa District was chosen for the study as one of the high occurrence locations for dengue. The study design was consistent with the two study objectives described above. In order to address the first objective, to examine the potential community, family and individual factors, the study sought to compare dengue infected and non-infected groups. Thus, 213 dengue infected respondents and a non-infected control sample of 100 respondents were identified and recruited from approximately 20 villages and 25 varying regions representative of Batticaloa district. Addressing the environmental, logistical, and practical challenges, a purposive-snowball infected sample and a random non-infected sample was gathered.

Sampling

A sample of 313 respondents were selected using a multi-stage sampling that included snowball-purposive and random sampling from 25 purposively selected communities (villages, or suburbs). In the first-stage, villages were selected from five administrative divisions (Kattankudy, Kaluwanchikuddy, Manmunai Pattu, Vellavelly, Paddipalai and Manmunai North) in the northern part of Batticaloa District. Villages were selected to maximise variation in village characteristics, such as house density, water availability, health problems, poverty and rurality. In the second stage, 10-20 individuals from each of the 25 communities were recruited for a total sample size of 313. Of the 313 participants, 213 were recruited using snowball-purposive sampling of physician confirmed dengue patients while 100 were uninfected randomly selected individuals.

Procedures

The data were collected through in person interviews with the selected participants. Trained health care workers with university degrees, university academics and health science university students worked voluntarily as interviewers. The co-principal investigators trained interviewers and supervised the data collection. In addition, field visits were made with interviewers at random to ensure data collection quality. Filled questionnaires were entered into an SPSS spreadsheet as the data collection progressed. The questionnaire, consisting of measures operationalising study concepts, was formulated by the study team, consisting of social epidemiologists (PI and Co-PI’s), and health professionals.

The questionnaire was pilot tested with a small group of infected and non-infected participants to improve understandability and ensure greater ecological validity. Dengue was diagnosed and differentiated from similar diseases through clinical features and platelets count by doing the dengue antibody test (Ig G + Ig M) at the Batticaloa hospitals.

Findings and discussion

The findings of this study generally support the hypothesised model. Spatial, community, family and individual characteristics uniquely contributed to dengue contraction in Sri Lanka. Hypothesised pathways explained 36%, 58% and 69% of the variances of proximal dengue risk, knowledge and preventive behaviours and dengue contraction, respectively. These findings support the study’s primary thesis that multilevel factors uniquely influence risk for dengue. The findings also point to the primary role of social/family factors, such as Familism and collectivism. More importantly, the findings elucidate the mediating role of individual knowledge and preventive behaviours linking distal factors and dengue contraction.

Familism refers to a collectivist orientation rather than an orientation toward personal success

Familism is reflected by multiple positive family characteristics, including communication, mutual support and care, and cohesion within the family. Previous family studies have shown that Familism is an important social-psychological resource necessary for the development of health/preventive knowledge and preventive behaviours. In the present study, these activities may include maintaining a mosquito-protected home and yard, healthy and preventive family habits, rituals and traditions, as well as family control over individual risk behaviours. The findings support this important role of Familism. That is, familism operates as a direct resilience factor that counteracts the deleterious influence of socioeconomic adversities on dengue risk. Thus, the findings illustrate the need for interventions to protect and strengthen families in dengue-risk exposed communities.

In addition, previous community studies have shown that perceived or experienced neighbourhood conditions are more proximal factors influencing psychosocial resources and behaviours of residents than are objective neighbourhood characteristics. This may be because perceived community collectivism captures both objective and subjective processes. The findings showed that collectivism in the community contribute to the knowledge and dengue preventive behaviours of residents. Thus, consistent with previous community research, perceived community collectivism has been shown to be an important resilience factor influencing dengue contraction in the present study.

The important roles of familism and community collectivism point to the need for enhancing and utilising these psychosocial resources. These resources can be utilised to enhance participatory preventive activities at the grassroots level, which are less costly and more effective than top-down recovery pro¬grams, planned and implemented by governmental and external non-governmental agencies. This can be ful¬filled by: (a) formally recognising grassroots groups and organisations; (b) creating formal links between national and divisional organisations/officers and grassroots organisations; and (c) providing information/training for prevention and materials for grassroots organisations.

Furthermore, the findings showed physical/spatial characteristics that detrimentally contribute dengue contraction. These characteristics include the rurality of communities, house density/clustering and proximity to stagnant water. It appears that spatially isolated, less-accessible and segregated communities are exposed to elevated risk for dengue contraction. Thus, local and central government policies and programs should focus on the improvement of these adverse structural conditions in these communities.

More importantly, the results showed that ethnic minority populations, the Muslim community in the present study, experience significantly higher risk for dengue contraction. This may be attributed to their behaviours, such as living in close proximity. Moreover, they may have less access to preventive and health services.

The findings identify important resilience factors that can directly reduce the risk for dengue contraction in residents. Residents who live in rural areas in developing countries are a specific sub-group vulnerable to infectious diseases such as dengue. This survey collected detailed socioeconomic, demographic and spatial infor¬mation from 313 residents in 25 villages in rural Sri Lanka. The authors believe that such a comprehensive battery of measures has rarely been used in the international infectious disease research literature. The findings of the present study also provide necessary suggestions and clues for future research that would exten¬sively examine infectious disease risk using improved research designs that include representative samples and optimal measures of study constructs.

(Dr. Thulitha Wickrama is Dean of Research, Colombo Institute of Research and Psychology; Dr. K.A.S. Wickrama is Georgia Athletic Association Endowed Professor, Department of Human Development and Family Science, University of Georgia, USA; Dr. Sukunan Gunasingham is Regional Director of Health, Batticaloa, Sri Lanka; Sivaguru Thanigaseelan is Assistant Director, NHRDC, Ministry of National Policies and Economic Affairs; and Saranya Sathiyavasan is Lecturer, Department of Human Biology, Eastern University, Batticaloa, Sri Lanka)