Saturday Feb 21, 2026

Saturday Feb 21, 2026

Wednesday, 14 March 2018 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

New model provides guideline to ensure patients living away from adequately-equipped hospitals are not deprived of prompt heart attack treatment

New model provides guideline to ensure patients living away from adequately-equipped hospitals are not deprived of prompt heart attack treatment

By Fathima Riznaz Hafi

Swift action during a heart attack is vital – it is one of the determining factors on whether a patient lives or dies. The failure to receive timely treatment usually is a result of the patient’s distance from a hospital that is equipped to treat heart attack patients – this is a situation that frequently occurs in the remote areas of Sri Lanka.

National Hospital of Sri Lanka Consultant Cardiologist Dr. Gotabhaya Ranasinghe points out that the inability to bring a patient to the hospital that has the required facilities, at the right time, results in lost lives and stresses that the efficient manoeuvring of heart attack care ensuring that every patient has access to emergency treatment, is vital.

In an interview with Daily FT, he spoke about the methods of heart attack treatment rendered in Sri Lanka, the current dilemma in receiving that treatment due to distance from adequately-equipped hospitals and the solution he proposes.

Heart attack treatment

“The general method of heart attack treatment is reperfusion therapy, mainly in the form of ‘thrombolysis’, ‘primary percutaneous coronary intervention’ or ‘pharmacoinvasive’ strategies,” Dr. Ranasinghe said.

“The key treatment for a person brought to the hospital with a heart attack is the Primary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention (PPCI), which must be given within two hours of the onset of chest pain. More than 50% of deaths can occur within the first two hours; therefore, the sooner the reperfusion is achieved the lower the rate of complications and death.

“PPCI is a non-surgical method of clearing up the occluded artery by deploying a stent – a metal, stainless steel mesh; it is the gold standard in treatment for heart attacks due to its superiority in outcome including considerable drops in recurrent attacks, haemorrhagic strokes and death rates.”

He further explained that PPCI can only be performed in the catherization laboratory of a hospital. There are more than 80 Government hospitals in the country but not all of them are equipped with this lab. Ideally every province should have a catheterization lab; but out of nine provinces, only six provinces have the lab.

People who live far away from the PPCI-enabled hospitals will not be able to get there within the required time and could die on the way. Under such circumstances, they should go to the nearest hospital in their area, where due to the unavailability of catheterization labs, they will be treated with thrombolysis as the reperfusion therapy, with agents – streptokinase or tenecteplase which should be administered within 30 minutes of the patient’s arrival at the hospital. Thrombolysis is available in all hospitals.

By doing so, they are removed from danger but must proceed thereafter to a hospital with a catheterization laboratory where they must be given Percutaneous Coronary Intervention (PCI) within 24 hours to ensure that the artery is fully opened, and patency is established with a stent.

Dr. Ranasinghe says thrombolysis is an effective treatment option but it is important to understand that this treatment should be followed by PCI within 24 hours. “When the patient is saved he feels better and goes home. This is not good. Following this treatment, he must proceed to a hospital that has a catheterization lab and undergo PCI; otherwise there could be complications later. The thrombolysis buys time until he is transferred to a hospital that provides PCI,” he says.

The combination of both these procedures (PCI and thrombolysis) is called ‘pharmacoinvasive’ therapy. It is not necessary for patients who live near the equipped hospital as they can get the PPCI treatment immediately. Pharmacoinvasive therapy is for the other group, who live too far to arrive on time to be saved. Such patients can die on the way and therefore pharmacoinvasive therapy is the ideal solution for them.

“Latest studies have shown that pharmacoinvasive therapy results are almost equal to PPCI,” he added.

Multi-level wagon

wheel triage and

transfer model

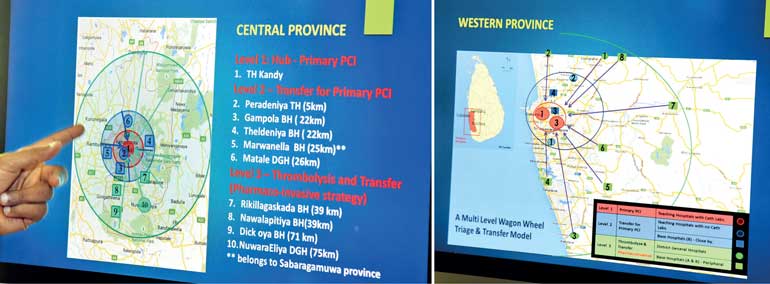

A new model called the ‘Wagon Wheel’ is to be introduced to ensure that this strategy is carried out smoothly in the event of a heart attack, implementing all three of the main reperfusion methods for acute heart attack management. A brainchild of Dr. Ranasinghe, the model is precise and provides a guideline on where the patients should head in the event of an attack. It ensures that there is a dedicated system for early treatment and transfer.

The model consists of three levels. Level 1 is the hub where PCI-enabled hospitals are located. Level 2 and 3 are determined by the geographical distance from the hub and time taken to transfer patients to the hub. Level 2, geographically closer to the hub, is to immediately transfer patients to the hub for Primary PCI within 30 minutes. Level 3 is for people living in places very far away from the hub (e.g. Ampara, Ratnapura, Chilaw and Polonnaruwa), who cannot be transferred within those critical two hours, in which case pharmacoinvasive therapy will be implemented, whereby they receive thombolytic therapy in a nearby hospital and are then transferred to the hub for PCI.

“Ideally, each province should have a catheterization lab; then it is not necessary to transfer the patients – they can conveniently receive treatment in their local hospital. Until this happens, an efficient and dedicated system such as the Wagon Wheel, needs to be implemented to ensure the smooth transfer of the patient,” Dr. Ranasinghe says.

The Wagon Wheel model will prevent unnecessary panic, chaos and wastage of time. With a dedicated system there is no confusion in where the patient should go. It is in its initial stages and once catheterization lab facilities are established in each of the nine provinces, the Wagon Wheel model will be in full operation. Dr. Ranasinghe is confident that this new model will be the ideal guide to patients in such emergencies.

He stresses that this initiative was made possible through the support of Minister of Health, Nutrition and Indigenous Medicine Dr. Rajitha Senaratne and adds that the Minister has been supportive in other initiatives in heart attack care as well.

“Up to 2015 all the patients who came to government hospitals for PPCI had to pay for the stents. Government hospitals had a limited number of stents because of the high cost of around Rs. 250,000 per stent. The patients had to buy them either through the President’s Fund or their own pocket. In 2015 the Minister introduced a system in the government hospitals, where every patient, rich or poor, receives the best quality stent in the world, free of charge. As a result, there was a big change from 2015 to 2016 – the number of patients coming for PPCI treatment in Government hospitals increased and death rates from heart attacks decreased. We are heavily indebted to the Minister for bringing about this change,” Dr. Ranasinghe said.

Pix by Kithsiri de Mel

“We treat around seven to 12 heart attack patients a day at the Colombo National Hospital. Coronary heart disease is a leading cause of death locally and globally and incidences are increasing. Fortunately, alongside this increase, treatment methods have also evolved; novel treatment techniques and medication have emerged to provide swift and efficient care during medical emergencies,” says Cardiologist Dr. Gotabhaya Ranasinghe.

Though content that Sri Lankan hospitals are up to date in many areas of medication, Dr. Ranasinghe notes a lacking in evolvement in one area – the use of Streptokinase, which is one of the thrombolytic agents used in the country for the past 20 years to treat heart attacks – he says it is almost obsolete in other countries.

“Two years ago, we introduced a new thrombolytic agent called ‘tenecteplase’, which is much better and has a higher success rate. The coronary patency rate of streptokinase is about 40% which is grossly inadequate, while having several side effects and limitations such as higher rate of stroke and intracerebral haemorrhaging and allergic reactions. The newer thrombolytic agent, ‘Tenecteplase’, a tissue plasminogen activator (tPA), has more than 80% patency rate, which is far more superior to streptokinase in the treatment of heart attacks.

“The number of lives saved for 1,000 treated patients within the first two hours of the infarction for streptokinase is about 40 and for tenecteplase about 65. Bleeding tendency is much less with tenecteplase than with streptokinase. In addition, compared to streptokinase, tenecteplase could be fast delivered in a single bolus to the patients and could be administered anytime, anywhere with rapid action.”

“With tenecteplase, when the ambulance arrives they can inject the agent then and there and the patient is saved immediately – we can dissolve the clot immediately – within seconds – whereas with the older agent, the patient must get admitted to the hospital because it is an infusion – a long, one-hour infusion,” he added.

Tenecteplase has been used abroad for many years but was not used in Sri Lanka due to the high cost. Initially it was Rs. 120,000 whereas streptokinase only costs around Rs. 5,000; there’s a big difference in cost.

“When we brought the matter to the attention of Minister of Health, Nutrition and Indigenous Medicine Dr. Rajitha Senaratne, he was very eager to help. He spoke with the company, and even brought the price down to Rs. 50,000. It is now available in most of the provinces at the cost of Rs. 50,000 per patient but provided free to the patient.

“Though tenecteplase has already been introduced in Sri Lanka, it is not yet being used all over the country but is slowly replacing the old one and we hope it will eventually be used throughout the country. Tenecteplase should be available in all peripheral, district and provincial hospitals,” Dr. Ranasinghe said.