Tuesday Feb 24, 2026

Tuesday Feb 24, 2026

Friday, 26 July 2019 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

New Delhi (Reuters): India moved on Tuesday to overhaul decades-old labour laws, some dating from British colonial rule, by introducing two key measures in Parliament that aim to make it easier for industry to meet labour standards and create more jobs.

|

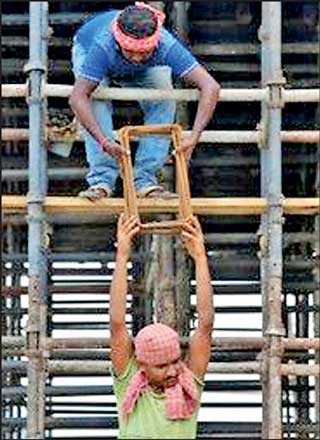

FILE PHOTO Labourers work at the construction site of a residential building on the outskirts of Kolkata, India, July 5, 2019. REUTERS |

Labour Minister Santosh Gangwar introduced the bills, covering safety, working conditions and wages, in the lower house of parliament, saying they would promote the ease of living and doing business.

“A historical step for ensuring statutory protection for minimum wages and timely payment of wages to 500 million workers ... has been taken,” Gangwar said as he sought lawmakers’ support.

The Code on Wages is the first of four proposed labour bills long envisaged to replace 44 archaic labour laws. It aims to set standards of minimum wages across industry, including small businesses, which employ nearly 90% of India’s work force.

It will repeal four labour laws, including one on wage payment passed in 1936 and one on minimum wages dating to 1948.

The other measure, a safety bill that proposes a single-registration, single-licence regime for companies, instead of multiple permissions under 13 labour laws, allows women to work night shifts.

Trade unions, however, protested, saying the government wanted measures to protect the interests of industry at the cost of workers.

“The government ignored our demands to fix minimum wages as per the International Labour Organisation’s guidelines and participation of trade unions in setting other standards,” said Sanjeeva Reddy, president of the Indian National Trade Union Congress, an arm of the opposition Congress party.

Trade unions will hold a nationwide day-long strike if Parliament approves the bills, he said.

However, the bills may face difficulties in the upper house of Parliament, where the government lacks a majority.

Industry welcomed the move, as helping to boost the competitiveness of domestic companies by lowering compliance costs.

“We welcome these two bills,” said M.S. Unikrishnan, chairman of the industrial relations panel at business grouping the Confederation of Indian Industry.

“But the government should also allow flexibility in retaining workers as well as freedom for automation to improve productivity.”

The wage code could fuel costs initially for some industries, though it provides for minimum wages to be fixed for five years, he added.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi made a labour market shake-up a part of his reform agenda after coming to office in 2014, but opposition from unions and a bruising battle to pass other key economic legislation have stalled his effort.

India’s two-decade streak of fast economic expansion is often derided as “jobless growth” since the service sector-led model has been capital- rather than labour-intensive.

More than 200 million Indians will reach working age over the next two decades, and generating sufficient numbers of jobs for perhaps the largest youth bulge the world has ever seen is among the toughest challenges facing the country.