Saturday Feb 08, 2025

Saturday Feb 08, 2025

Friday, 12 January 2018 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

LONDON (Reuters): British industry enjoyed solid growth in November, benefiting from a global upturn that has allowed the economy to outperform gloomy forecasts made after 2016’s Brexit vote, although it still lags behind its international rivals.

LONDON (Reuters): British industry enjoyed solid growth in November, benefiting from a global upturn that has allowed the economy to outperform gloomy forecasts made after 2016’s Brexit vote, although it still lags behind its international rivals.

The British economy grew more slowly than all other Group of Seven members in the first nine months of 2017 as consumer-facing sectors suffered from a surge in inflation caused by sterling’s post-Brexit vote plunge.

With departure from the European Union set for March 2019, few economists think growth will improve this year.

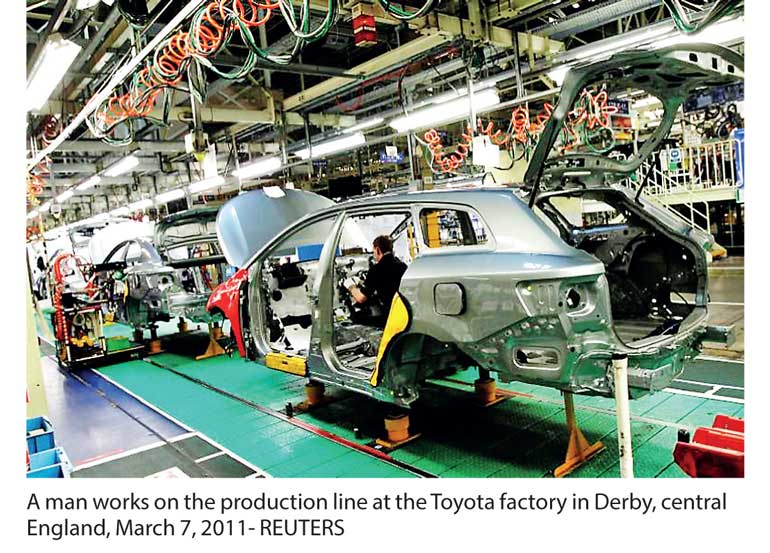

But the latest official data signalled that industry remains a bright spot: Manufacturers recorded their fastest annual growth since March 2011 in the three months to the end of November, expanding by 3.9% year-on-year.

The sector, which accounts for around a tenth of British economic output, also posted its seventh consecutive monthly expansion – the longest unbroken run in more than 20 years.

The National Institute of Economic and Social Research (NIESR) said the figures pointed to GDP growth of 0.6% in the last quarter of 2017, which would be the strongest of the year and would lift full-year growth to 1.8%.

The Bank of England said in November it expected growth to stick at 0.4% in the last three months of the year, after it raised its key interest rate for the first time since 2007.

If growth turns out faster, it might boost the chance of the BoE raising rates again in May rather than later in 2018 as most economists expect. Financial markets were unmoved by the data, however.

“The UK will need more than just strong industrial production figures though if it is to fare well,” said Christian Jaccarini, economist at the Centre for Economics and Business Research consultancy.

Construction output in the three months to November contracted 2.0% compared with the previous three months, the biggest dip since August 2012, the Office for National Statistics said.

Earlier on Wednesday, the British Chambers of Commerce said the economy looked set for an “underwhelming” 2018, with business subdued ahead of Brexit and reluctant to invest, according to its quarterly survey – the largest of its type. The ONS said industrial output rose by a monthly 0.4% in November, compared with 0.2% in October, the ONS said, spurring an annual rise of 2.5%. Economists taking part in a Reuters poll had expected to see output rise 0.3% on the month and 1.8% on the year.

“There was strong and widespread growth across (British) manufacturing with notable increases from renewable energy projects, boats, planes and cars for export,” ONS statistician Ole Black said. Goods export volumes in the three months to November were 9.1% higher than the same period in 2016, though the goods trade deficit exceeded all forecasts in a Reuters poll. Other countries are doing better. German industrial output rose by 3.4% in November alone, its biggest gain since 2009 and one which puts the economy there on track for growth of at least 2.2% last year.

Figures for Britain’s services sector – which is around eight times the size of manufacturing and has been growing slowly – are due out on Jan. 26.

Wednesday’s data showed Britain’s total trade deficit, which includes goods and services, hit a five-month high of 2.8 billion pounds in November.

LONDON (Reuters): Britain could lose almost 500,000 jobs and 50 billion pounds investment over the next 12 years if it fails to agree a trade deal with the European Union, according to a report commissioned by London Mayor Sadiq Khan.

Cambridge Econometrics, an economics consultancy, looked at five different Brexit scenarios, from the hardest to the softest form of Brexit, and broke down the economic impact on nine industries, from construction to finance.

The study said that in a no-deal scenario, the industry that fares the worst will be financial and professional services, with as many as 119,000 fewer jobs nationwide.

“If the Government continue to mishandle the negotiations we could be heading for a lost decade of lower growth and lower employment,” Khan said. “Ministers are fast running out of time to turn the negotiations around.”

Britain and the EU will soon begin the much harder task of defining their future trading relationship, after settling the broad terms of their divorce settlement last month.

A stand-off between Britain and the EU over the future access to single market for London’s vast financial services industry is shaping up to be one of the key Brexit battlegrounds before Britain is due to leave the bloc in March 2019.

Discover Kapruka, the leading online shopping platform in Sri Lanka, where you can conveniently send Gifts and Flowers to your loved ones for any event including Valentine ’s Day. Explore a wide range of popular Shopping Categories on Kapruka, including Toys, Groceries, Electronics, Birthday Cakes, Fruits, Chocolates, Flower Bouquets, Clothing, Watches, Lingerie, Gift Sets and Jewellery. Also if you’re interested in selling with Kapruka, Partner Central by Kapruka is the best solution to start with. Moreover, through Kapruka Global Shop, you can also enjoy the convenience of purchasing products from renowned platforms like Amazon and eBay and have them delivered to Sri Lanka.

Discover Kapruka, the leading online shopping platform in Sri Lanka, where you can conveniently send Gifts and Flowers to your loved ones for any event including Valentine ’s Day. Explore a wide range of popular Shopping Categories on Kapruka, including Toys, Groceries, Electronics, Birthday Cakes, Fruits, Chocolates, Flower Bouquets, Clothing, Watches, Lingerie, Gift Sets and Jewellery. Also if you’re interested in selling with Kapruka, Partner Central by Kapruka is the best solution to start with. Moreover, through Kapruka Global Shop, you can also enjoy the convenience of purchasing products from renowned platforms like Amazon and eBay and have them delivered to Sri Lanka.