Thursday Feb 26, 2026

Thursday Feb 26, 2026

Thursday, 26 March 2020 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

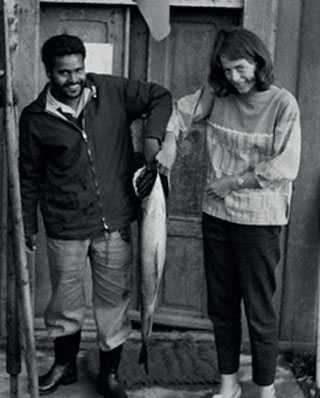

Sigrun in her Jaffna home

By Chandani Kirinde in Jaffna

When 21-year-old Norwegian Sigrun Haugstad arrived in Jaffna in 1967 with her husband Anthony Rajendram and their two young children, her presence in the conservative northern town was somewhat a novelty, with few people accustomed to seeing a “white person” in their midst. Her mere presence attracted rows of people to pile past their house eager to catch a glimpse of her and when she stepped out of the house, she was followed by curious onlookers, children and adults.

|

| Sigrun with daughters Siv (2) and Rannveig (5) with some of the local ladies who provided the meals |

|

| Anthony enjoying lunch with Cey-Nor workers in 1969 |

|

| Sigrun and Anthony in 1963 |

|

|

“Strangers would come into the gate and see if the ‘white’ woman was there. The children and adults would be gawking, not just staring, without in the least being embarrassed – and that takes a bit of getting used to. It was an irritant to begin with,” says Sigrun of her early days in Jaffna.

But that was then. Today she is no longer an “outsider” in Jaffna but very much an insider, speaking fluent Tamil, accustomed to local customs, and moving about with ease of a native of the northern town.

Anthony’s dream

Her arrival in Jaffna in 1967 was the result of a chance meeting with a young man who had left the northern town in the late 1950s with a friend, hoping to reach England overland to study modern fishing. Hailing from the coastal village of Gurunagar, Anthony Rajendram had been moved by the plight of the fishing community in his hometown, and was eager to learn about modern fishing methods so he could return and apply those to local communities to improve their living standards.

“He left Jaffna with his friend on a motorbike, eager to get out of Jaffna and the island and reach Europe. They ended up in Lebanon and were stuck there for a while having run out of money and had to await replenishment of their funds from back home. His friend received the money first and he proceeded to England, but Anthony had to wait a little longer, and here he put this time to good use by joining a group of international workers from an organisation called Service Civil International that had organised a work camp to help people in a village outside Beirut, which had been affected by a earth slide.”

What caught on for Antony was “free food and free lodging,” says Sigrun, adding that the chance to get to know people from several countries was also an equally attractive proposition.

“My husband loved the idea and the people, and he stayed on with them, even after he got money from his mother, till the work was over, and contacted the same organisation when he got to London eventually. Here he was told by some of the people he met that the best place to study modern fisheries was not England, but Norway. He then moved to Norway, where he was put in touch with my aunt (my mother’s sister), who was the President of Service Civil International, and he became a house friend. When he decided to come to Stavanger, the town where I grew up on the south west coast of Norway, my aunt of course told him to go and stay with her sister (my mother) and that was how we met.”

Similar to how her presence in Jaffna was a novelty in 1967, Anthony’s presence in the Norwegian town too was unusual.

“I had heard about this strange person from my aunt before I met him. There were a very few foreigners from such far-off countries those days, and we knew little about Ceylon. Leave alone Jaffna, I did not know anything about Sri Lanka (Ceylon), and when I went to the library before coming here to read up on the place, all I found was some very boring historical stuff, which gave me no feeling about what kind of places this was. The closest I came to Ceylon was Rabindranath Tagore,” she says light-heartedly.

Sigrun and Anthony became inseparable from the time they met, and travelled around and decided to get married in 1964. “My parents were teachers and I was their only child. They were taken by surprise by our decision, but they were too polite to make a scene. All my close family members considered themselves worldly in their outlook, so when Anthony and I decided to get married, they were accepting of our decision.”

Sigrun comes to Jaffna

By 1967, the couple had two children, and Anthony, having studied fishing methods in Norway for three years, was eager to return home and help the local fishing community. “From the start I knew moving to Jaffna was part and parcel of our relationship. I was keen to learn more about the place my husband loved so much,” says Sigrun.

The few foreigners who Sigrun met at the airport in Colombo on her arrival asked her why she was going to Jaffna, told her it was too far and too hot, and said Colombo was better. “I had very mixed feelings at the time. It was a bit of a shock .There was little to prepare myself for this country, climate-wise and otherwise.”

But soon she was put at ease with her mother-in-law and her husband’s two sisters and brothers, who welcomed her and accepted her as she was.

“They also did not expect me to dress in a traditional way. No one expected me to wear the long housecoats, which had replaced the sari as the home-wear for ladies by the time I came there. Going to a wedding, I wore a sari and that was appreciated.”

After some time in Jaffna, the couple moved to Kayts with the children. The late ’60s in the country was a time when essential items were in short supply, with sugar, kerosene, and diesel all rationed.

“When we moved to Kayts, we had a generator, but when there was no diesel for it, there was no electricity. We had to draw water from the well, and when there was no kerosene for the cooker, we used firewood. I stitched my own clothes as well as the children’s clothes whenever I could get any material. I was very young, and my days were busy with the children, and I was also involved in the project my husband had started, so there was no time to sit around and contemplate.”

Coming from a country with lots of mountains, rivers and waterfalls, Sigrun initially found the northern landscape almost boring, but gradually fell in love with the place. “For recreation we spent time on the causeway between Jaffna and Kayts, where the sunsets are beautiful. Then there were all the plants, the mangoes, and plantations, and so Jaffna grew on me.”

Dream project begins

While Sigrun was settling down to her new life in Jaffna, Anthony got started on his dream project to help better the lives of the fishing community.

“My husband grew up in a comfortable home, with a grandfather who was a big contractor who undertook many major projects, not only in Jaffna but other parts of the country as well. His father had died while he was young, but Anthony had a comfortable life but was forbidden to play with the children of the fishermen. This did not however stop him. He would sneak out in the middle of the night to go fishing and play with them, which gave him an insight into the difficulties they face.”

Starting a project meant also getting funding, and it took several years for Anthony to get the necessary support for his work.

“Initially he tried to interest the Government, but they were not interested to do anything in the north at all, and then he came back to Norway and worked for a while with the humanitarian organisation CARE. Then he thought of starting something on his own, for which he needed funding. The Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation which Anthony approached had promised to partly fund the project, if he could get another Norwegian organisation interested in it, and this support he found in the Norwegian Templars Organisation, and then he started his work at Karainagar setting up a Foundation called ‘Malu-Meen,’ coining together the Sinhalese word for fish ‘maalu’ and the Tamil word ‘meen’. Later he felt the name wasn’t right and changed it to Cey-Nor (Ceylon-Norway) Development Foundation.”

The family lived in Kayts for two years while the project was in progress, with Sigrun handling the English correspondence for Cey-Nor. As someone who had been always interested in languages, she was also learning Tamil, word by word, and new skills as well.

“They were building boats, and I did not know anything about boats. But there were these leftover materials after the boats were built, and we used the extra wood to make furniture and kitchen cupboards. I tried my hand at whatever I could.”

As the project progressed, problems set in with a fallout of ideas, with Anthony focused on improving the lives of the fishing community, and clashing with those of people who got involved from Colombo.

“My husband’s idea was to benefit the locals, whereas they were more interested in the money part and exports. He was very keen to continue with the work, but eventually it came to a point where my husband decided to pull out.”

A long exile

The family stayed on till the end of 1972, except for a very brief trip back to Norway, but after their elder daughter had an accident and lost sight in one eye, they decided to go back as there were no specialists in Jaffna at the time.

“We went with the idea of returning, but then the children started going to school and then the option was to return for a few months when time permitted, so the children could keep contact with Jaffna. We came back came in ’80/’81 for about 10 months, and that was when the Jaffna Library was burnt down. I still remember passing the library in my car, and seeing the building burning the next morning.”

After they left Sri Lanka in 1981, things in the country and particularly in the north got progressively worse, and then after the riots of 1983, there was little chance for them to return. Anthony died in Norway in 1990 at the age of 59, before he could make another visit to his beloved Jaffna.

“My husband was a romantic in many ways, which is also why he fell in love with the social service organisation he first encountered in Beirut. The ideas always stayed with him. That was also his drawback. When the unrest really caught on here and then led to the war, he was very disappointed. He took it very personally. He was really hurt.”

As the war raged here, people from the north began fleeing to Norway as refugees and Anthony, who was the first Tamil to go and settle in the country, became somewhat of a legend among the Tamil community there and remains so till today. But Sigrun says there is a difference between the people who fled the war to come to Norway and her husband. “He found he was caught up in exile, which was not by choice. After 1983 he couldn’t go back.”

For Sigrun, too, it was a long exile from Jaffna which she had grown to love and had become her home. In the early 2000s, when her son came to Colombo on an assignment, Sigrun decided to join him, unsure if she could make it to Jaffna, given all the restrictions that were in place for travellers to the north.

“I joined him with the hope that I could visit Jaffna. I managed to get a permit for four days and travel there on a Russian plane and a Russian pilot who looked drunk. It was shocking. A lot had changed. So many buildings lay in ruins as we drove from Palaly to Jaffna.”

Sigrun returns

When the Ceasefire Agreement was signed in 20002, Sigrun returned once again with the idea of getting a place for herself in Jaffna.

“My mother had left me some money and I wanted a house for myself here. I did not find a place I liked in 2002, but I let a good friend of my husband know I was interested in buying a house in Jaffna, and to let me know if there was a place that I might like. In 2003 he sent me a letter saying he had found a place, and asked me to come quickly if I was interested. I did and bought this house,” Sigrun recollects.

After her return to Norway, Sigrun did her higher studies in Social Anthropology and worked for years with the Norwegian Immigration authorities, and retired at 64 because “there are things I would like to do rather than going to work every morning.”

Her long years living in the country as a foreigner and learning to adjust to a new way of life also opened her eyes to some problems that are common to migrants all over the world. “Unless you have a clique, unless you have somebody with the same experiences, you can feel like a fish out of water. And I did sometimes feel that way in Jaffna, that much I must confess.”

A friendship that has stood the test of time is with Vaisala, who she first met in Jaffna in 1967 and who became the elder sister she never had, and is someone Sigrun still visits in Canada.

“She was quite the talk of the town in Jaffna when I came there first. Her husband was an engineer and they had lived in Australia and came back to Sri Lanka, and later moved to Jaffna. All the things I had heard about her, that she was wearing skirts and dresses, she was seen driving a car, she had been seen with a cigarette and a glass of brandy, and she was a Jaffna woman and that made it even worse.”

But when Sigrun met her, they hit it off quickly, and Vaisala turned out to be her closest friend. “I could discuss anything with her. I had the feeling no one knew me here. My husband, yes, but he wasn’t always around. We had the very same experience which is why she became my saving grace.”

She now spends a few months here whenever she can. “I want to keep coming back as long as I can. I would like to come more often too, but I must spend time with my children and grandchildren and I have so many close friends, and they live in different countries. When I stay several months here, I feel I lag behind the other things I want to do.”

Writing her husband’s story

At the age of 74, Sigrun still has many things she wants to do, and one thing close to her heart is writing her husband’s story, for the sake of her grandchildren.

“His story is multi-faceted. The whole thing about Cey-Nor was a tragedy in many ways as far as we are concerned, but it’s also the story of early Norwegian involvement in Sri Lanka. There are some who have tried to give direction to the story I want to tell, saying emphasis must be on the migration aspect, as he was the first Sri Lankan Tamil to settle down in Norway. The migration of Tamils to Norway is very much linked to his coming there early on, so much so that Anthony Rajendram has become somewhat of a legend for the Tamils in Norway – part of that is fact-based, part of that is fiction. I find it difficult to place myself in this story. This is my voice and it is based on what he has told me about his childhood. I will have to balance the story and it must be honest.”

Cey-Nor, which Anthony Rajendram started with a lot of love and toil, was taken over by the Government in later years, and now functions under the Ministry of Fisheries. It advertises itself as an organisation that has come a long way from making primitive timber boats at its initial stage in 1967, but what almost everyone in Sri Lanka has forgotten is that it was the dream of one man who left Jaffna in the late 1950s on a motorbike, with the ambition of learning new skills to help his follow citizens, that laid the foundation for the start of this organisation.

While others may have forgotten, it is a story that Sigrun holds close to her heart. It’s her love for a man and his land. And more than five decades after she first set foot in Jaffna, the hold the place has on her remains as strong as ever.