Saturday Feb 21, 2026

Saturday Feb 21, 2026

Friday, 30 June 2023 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

He dreamt of how he would do all the good he could to the lives of the workers who lived and worked in the tea plantations

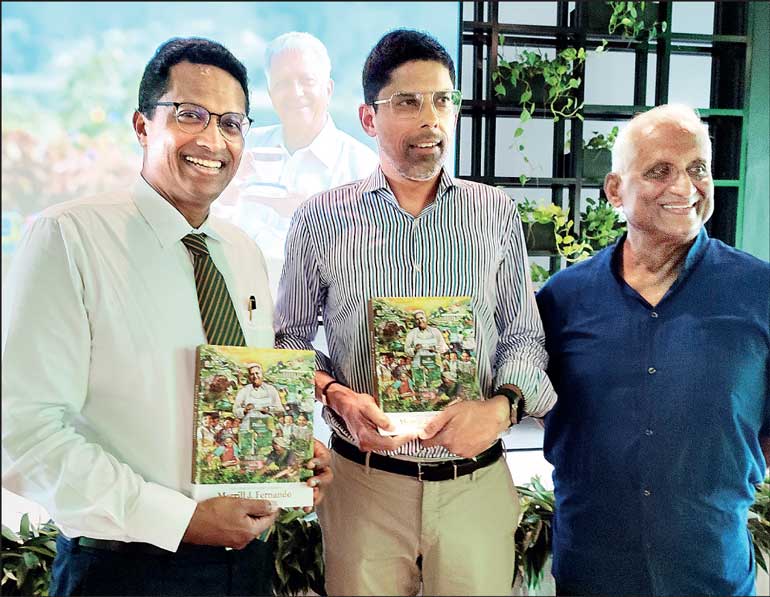

Dilhan Fernando, Malik Fernando and Anura Gunasekera at the launch of “The story of Ceylon Teamaker; Merrill J. Fernando: Disruptor, Teamaker, Servant”

By Surya Vishwa

The Daily FT, publishing the first section of the life story of the founder of Dilmah Tea, announced the serialising of three follow up reviews as the book ‘The story of Ceylon Teamaker, Merrill J. Fernando’ doubles up more as a life story of Ceylon Tea, and a contemporary global and local history guide to the interweaving of post-colonial diplomacy, trade and politics.

The book would serve as an inspiration for those such as policymakers, entrepreneurs, development practitioners and even diplomats to study how a cash crop could bind countries beyond profit. It was stated in the first review segment that The story of Ceylon Teamaker is a story of sowing opportunity and showcasing it to the world, creating a brand that promoted not just tea but the whole of Sri Lanka – with its spices, herbs, medicinal knowledge and traditional food; and that the root of the love for all these was encased in the childhood of Merrill J. Fernando.

The initial review ended with the beginning of chapter 5 titled ‘The shaping of my future’, describing how Merrill developed a love for tea and tea plantations, visiting the estates of Punduluoya and Kotmale districts owned by the family of S. Thondaman who later became the President of the Ceylon Workers’ Congress (CWC).

The initial review ended with the beginning of chapter 5 titled ‘The shaping of my future’, describing how Merrill developed a love for tea and tea plantations, visiting the estates of Punduluoya and Kotmale districts owned by the family of S. Thondaman who later became the President of the Ceylon Workers’ Congress (CWC).

Today we continue from Chapter 5 to Chapter 10. Chapter 5 is an account of how young Merrill abandoned the ambition to become a lawyer, and instead submitted his application to a call announced by the Tea Controller in 1950 to recruit locals as tea tasters. Tea tasting was a domain held steadfastly in the hands of the British, as did the tea industry in much of post-independence years.

“The British who dominated the tea business then, were of the view that locals did not have the palate to make good tea tasters, as they consumed too much spicy food,” states Merrill in his book. Taking up his very first challenge in the tea industry monopoly held by the British, Merrill applied for a position in the first batch of tea tasters. The tea industry landscape in the island was changing and the British controlled plantation managements were beginning to recruit Sri Lankans. His first steps at entrepreneurship was while training as a tea taster, and started supplying tea in bulk to small shops around Negombo, paying careful attention to quality. His first car, a Morris Minor was bought with the profits he earned.

His first indoctrination in the tea industry as a whole was at Heath and Company, the largest exporter of tea at the time to Australia, New Zealand, United Kingdom, South Africa and Iraq. Soon he was offered a training opportunity in London at J. L. Lyons, the then UK tea giant. While arrangements were going on, a sudden detour in career, landed him at the Mobil Standard Vacuum Oil Company, through a family member who had arranged for him to be interviewed for a higher pay (Rs. 1,500 with incentives) as a Retail Merchandising Assistant, reporting to C.A. Kelson, an American marketing specialist. It was too tempting an offer for a 22-year-old who then temporarily abandoned his still young love affair with tea to tour the island visiting gas stations.

Within a year he was promoted as regional inspector, synonymous with the role of regional sales representative. The task of young Merrill was to effectively counter the competition with Shell and Caltex Oil companies through new fuel distribution centres. Although it was not the tea business, the young man learned the basic premise of ethics in work life, developing an abhorrence for gifts or rewards by clients or in official deals, the correct word for which fell into the terminology of ‘bribery’ the scope for which he realised was rampant in this new line of business. It seemed the norm for company inspectors to accept bribes from potential investors to the company’s petrol and service stations.

“My conscience did not permit me to accept gifts or other rewards from clients, for doing a job for which I was paid a regular salary by my employer,” notes Merrill Fernando, recalling the earliest makings of the youth who would as a man stand steadfastly by these principles. His stint with the oil industry, inspecting and supervising gas stations around the island made him familiar with the Sri Lankan landscape and gave him ample opportunity and freedom to study the geographical dimensions of the diversity of Ceylon Tea.

Re-entering the tea trade

Chapter 6 titled Re-entering the Tea Trade – A. F. Jones, traces how Merrill returned to the tea fold – this time to a British owned family business A. F. Jones & Co. Ltd. The company was owned by the father A. F. Jones and his two sons, Dennis and Alan. The winter of 1954 saw Merrill in London, his very first overseas visit, travelling in the vessel, SS Himalaya on its maiden voyage from Australia to London. His training was to be with tea experts Joseph Travers Ltd., whose offices were located near Mincing Lane, which was the tea centre of the world.

Chapter 6 titled Re-entering the Tea Trade – A. F. Jones, traces how Merrill returned to the tea fold – this time to a British owned family business A. F. Jones & Co. Ltd. The company was owned by the father A. F. Jones and his two sons, Dennis and Alan. The winter of 1954 saw Merrill in London, his very first overseas visit, travelling in the vessel, SS Himalaya on its maiden voyage from Australia to London. His training was to be with tea experts Joseph Travers Ltd., whose offices were located near Mincing Lane, which was the tea centre of the world.

Living in England in the basement flat of a widowed elderly lady at Kingston Place, at 2.10 pounds per week, travelling in the underground from Notting Hill Gate to Bank Station, the office where he had his training, viewing the first snowfall, making new friends and colleagues and securing a full training on the competition of tea in London, the young man returned with a changed vision and outlook. He was happy with his training but deeply affected by the fact that Ceylon tea was grossly exploited in London. Its pure taste was not reflected, mixed with diverse teas of different origins and passed on as Ceylon Tea. He was also affected by the fact that the dividends of the industry did not trickle into the hands of those who enabled the trade to function – those who plucked and toiled in the tea plantations, living in cramped conditions and paid a pittance.

The purpose of his visit to London was to learn branding and marketing; the two core components of the industry dominated by British based companies, where Ceylon tea in Britain did not showcase the pulse of Ceylon, as the country was known then. Tea seemed well and truly a colonial product where both profit and persona were British.

Exploitation of Ceylon tea

Chapter 7 is titled Exploitation of Ceylon tea in London. Merrill explains in the first paragraph; “I was deeply distressed by the ruthless exploitation of our tea industry and its workers that took place in London.” He goes on to note:

“A very significant weight of our tea, I think around 60 million pounds annually, was consigned then to the London auction, which was a terminal market. From London, tea was re-exported in bulk and in value added form, packaged and branded, with its main destination being the US, Canada, Northern Europe and Japan. Initially, most of the packaged tea contained a large component of Ceylon Tea, blended with tea from other cheaper origins.” These diluted brands were passed off as Ceylon Tea. He notes that export companies operating from Rotterdam and Hamburg also engaged in similar exploitation, pointing out that in the face of this onslaught, the Sri Lankan authorities responsible for oversight remained passive, turning a blind eye to the defilement of Ceylon’s tea.

This started in young Merrill the churning of idealism where he promised himself that he would start his own brand announcing single origin 100% pure Ceylon Tea. He dreamt of how he would do all the good he could to the lives of the workers who lived and worked in the tea plantations. He wanted to use tea as a route to eradicate poverty and create an ideal world, as much as possible. The few he shared his dreams with laughed at his idea.

This started in young Merrill the churning of idealism where he promised himself that he would start his own brand announcing single origin 100% pure Ceylon Tea. He dreamt of how he would do all the good he could to the lives of the workers who lived and worked in the tea plantations. He wanted to use tea as a route to eradicate poverty and create an ideal world, as much as possible. The few he shared his dreams with laughed at his idea.

Pure Ceylon tea

He did not realise then, that he would certainly do it, some two decades later, once he mastered to combat the power and manipulation that governed the industry. Yet, the entire philosophy, ethic, patriotism and philanthropy we see in the brand of Dilmah which is now a household name in the world representing Sri Lanka and 100% pure Ceylon tea, was ingrained in the mind and heart of its founder, when he was still a rather helpless bystander of the abuse of Lankan tea in London, the world’s tea centre.

Returning from London to A. F. Jones, he asked his employer why they did not export value added tea and was given the answer that they did not know how to do it and that the best place for it was London. Merrill had not agreed to this in his heart but remained silent. Soon he was given more responsibilities usually assigned to the Jones’ sons. When one of the sons, Dennis, was hospitalised for three weeks, Merrill carried out all his duties. His ability was praised and his employer entrusted him with very high responsibilities in the business as much as they would, a family member.

First overseas business visit

Chapter 8 titled ‘My first overseas business visit’, relates how the trade is carried out in Japan where he was sent on his first overseas business assignment – in the year 1960 – with a dire warning to be ultra-careful in how he deals with the Japanese agents; H. J. Kramer Ltd., a company headed by a German national who had previously sent only the British on business interactions. His doubt of the ability of a ‘local’ representative had been thinly concealed but soon Merrill would have completely won over the Japanese directors of the company much to the surprise of Otto Gerhardt, the German head of the firm.

The result of that visit, which included learning to discern between a Darjeeling and a Japanese black tea and learning that Japan, noted for their green tea, also produced black tea, was a fourfold increase in business between the Japanese company and A. F. Jones. This had exceedingly irritated Claude Godwin, then Lipton’s Managing Director who had forbidden Merrill ever to visit Japan again!

The result of that visit, which included learning to discern between a Darjeeling and a Japanese black tea and learning that Japan, noted for their green tea, also produced black tea, was a fourfold increase in business between the Japanese company and A. F. Jones. This had exceedingly irritated Claude Godwin, then Lipton’s Managing Director who had forbidden Merrill ever to visit Japan again!

USSR market

Chapter 9 deals with one of the most important sections in the book, titled ‘USSR market’. This chapter helps the reader understand the interweaving of local and global dynamics that affect an industry. It unravels the repercussions of the 1956 general election that swept out the United National Party (UNP), ushering in the Mahajana Eksath Peramuna (MEP) coalition led by S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike. The policies of the MEP under Bandaranaike were anti-imperialist which brought the Union of Soviet Socialist Republic (USSR) closer to Sri Lanka with the establishing of the first USSR-Russian embassy in the country. The beginning of this diplomatic relationship in 1957 led to the beginning of taking not only the Ceylon tea trade to a new height but also that of rubber, coconut oil and coir products.

Russia, a traditional large scale tea drinking market, was a purchaser of Lankan tea since the 1890s, but purchased their black tea mainly from China.

Soon Merrill Fernando was introduced to the new USSR Ambassador in Sri Lanka, Alexander Nikolaevich Yakodev who requested assistance to set up a tea trade facility on Thurstan Road, Colombo which was completed in 1958. Merrill was entrusted with supplying the entire USSR requirement of Ceylon tea.

“I did not realise how big the business was until the orders arrived,” recalls Merrill in this chapter.

“The rapid and unexpected increase in Russian buying had a significant impact on the auction, as our large purchase of high grown tea became a regular feature. It resulted in A. F. Jones becoming the sole buyer on behalf of Russia and a big player in the auction. The Jones family was very grateful for my contribution to this welcome business development,” he notes. The Russian market obtained for A. F. Jones through Merrill was thus handled by the company until the Sri Lankan Government entered into a direct agreement with the Russian administration and tea buying was entrusted to Consolexpo. It is pointed out that rubber buying by the USSR which was also lucrative was carried out under the supervision of business manager, now turned statesman, Karu Jayasuriya.

Merrill’s unique ability to genuinely win over people, with true faith and genuine goodwill earned him contacts both locally and globally. Globally, he made contacts at the highest level in the tea trade, overall business, diplomacy and political arena at a relatively young age. In the USSR this was achieved at prestigious levels. His friend the USSR Ambassador in Sri Lanka, Alexander Nikolaevich Yakodev would become Gorbochev’s closest ally. He was replaced as Ambassador to Sri Lanka by Rafiq of Uzbek origin who also became a trusted friend of Merrill. Rafiq went on to serve as the Presidium of the Uzbek Soviet Socialist Republic. Merrill points out that these contacts helped him in good stead when he started the Dilmah tea brand.

New political direction

Chapter 10 titled ‘New Political Direction’, details the local policies of 1957 and 1958 as well as its impacts beyond trade and industry. This and five more chapters will be analysed in the next segment of the review where the transit from a closed economy to an open one and its repercussions in the tea industry will be discussed. It is in those chapters that one hears of the start of Dilmah, the dream harboured for almost three decades by a youth who did not give up and shaped idealism into realism having matured as a tea industrialist through sheer commitment and dedication.