Sunday Feb 22, 2026

Sunday Feb 22, 2026

Wednesday, 20 February 2019 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Sanda Wijeratne

F. Scott Fitzgerald famously wrote that: “The test of a first-rate intelligence is the ability to hold two opposed ideas  in mind at the same time and still retain the ability to function.” To succeed and to maintain that success, companies today are forced to perform a similar feat of ambidexterity. They need to be focused and efficient in running day-to-day business, while simultaneously maintaining a broader perspective and reinventing their offerings to match changing market dynamics.

in mind at the same time and still retain the ability to function.” To succeed and to maintain that success, companies today are forced to perform a similar feat of ambidexterity. They need to be focused and efficient in running day-to-day business, while simultaneously maintaining a broader perspective and reinventing their offerings to match changing market dynamics.

Run & Reinvent

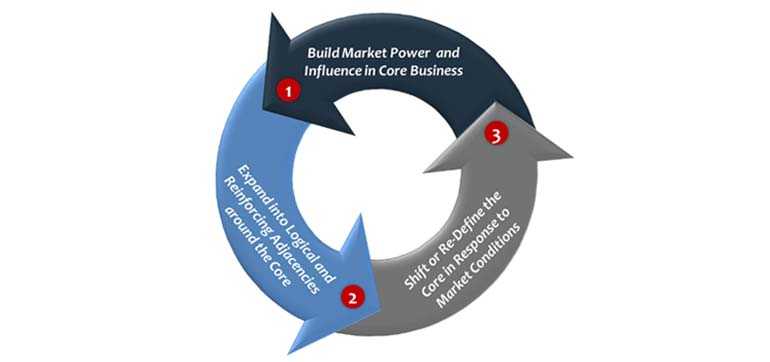

In strategy parlance, this skill of ambidexterity is known as the need to concurrently ‘Run and Reinvent’ (see Diagram 1). Derived from the classic exploitation vs. exploration organisational theory of the early ‘90s, it is a concept that is even more relevant today.

For companies, the challenges of exploiting the usual safe bets while exploring new options give rise to many practical questions: how are scarce resources to be allocated to these two areas? Do we need completely different teams for both running and reinventing to be optimal? Which innovative idea(s) should we back? Very few companies manage to answer these questions well and in a timely manner. Outstanding organisations like Amazon and Toyota appear to have hit on the magic ambidextrous formula, but most enterprises focus on one aspect at the risk of neglecting the other.

Too much Run

There are many global examples of companies that fell into a success trap – growing complacent, becoming over-reliant on their established offerings, and not paying adequate attention to innovative ideas. Perhaps the most famous of these is Kodak. One of its own engineers invented the digital camera as early as 1975, but short-sighted management decided to keep it under wraps to protect its core business of film reels and paper. And the rest of course is history, as is much of Kodak’s business.

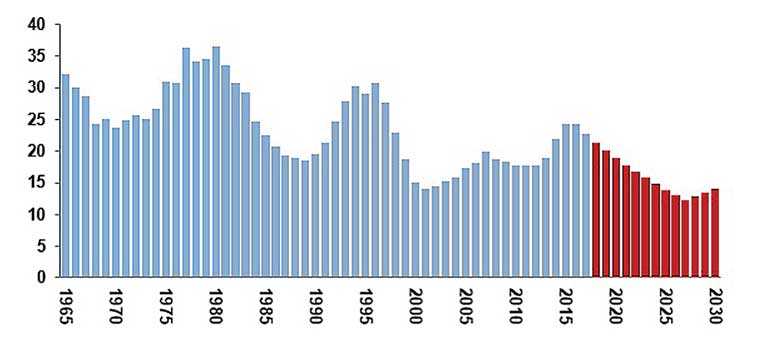

In 2012, while Kodak was filing for bankruptcy, an innovative company called Instagram literally cashed in on the digital photo trend – being bought over for $ 1 billion by Facebook. Closer to home, we see how lack of innovation in the tea industry has contributed to Sri Lanka’s falling market share while Kenya has made inroads with clonal varieties like purple tea. Companies at the top are now finding it increasingly harder to stay there unless they reinvent to match market disruptions. A 2018 analysis by Innosight found that the average number of years a company spends on the S&P 500 list has declined sharply over the past five decades. While companies spent an average of 33 years on the S&P 500 in 1964, this tenure had dropped to 24 years by 2016 and is forecast to reduce to 12 years by 2027 (see Diagram 2).

Industries with the highest rates of exit from the list include retail, financial services, healthcare, telecom, and travel. It is no accident that these are verticals that have already been highly disrupted and are susceptible to further disruption. It is even more vital for enterprises in such industries to ensure that they have a clear strategy plan in place to address disruption and the need for reinvention.

Too much Reinvent

While less common, companies may also falter if reinventing is given precedence at the cost of efficient operations. Although exploring new ideas is necessary, they may take a long time to materialise, not be measured properly, and/or start affecting the profitability of the organisation – as exemplified by Ericsson. Innovation was always important for Ericsson and by the late ‘90s, it employed 30,000 people across 100 global R&D centres.

This innovation however did not adequately translate into revenue. With profits in steep decline, Ericsson shuttered many of its R&D centres and laid off over 40,000 employees in 2001/02 alone, eventually returning to profitability in 2004.

Diversification is another route that many established firms take to reinvent themselves. However, over-diversification and lack of focus can also be dangerous, as iconic company Philips discovered. Philips was the undisputed leader in lighting and electronics worldwide from the ‘50s to the ‘80s. However, its extreme product diversification – they were making everything from toothbrushes to microchips – made it a bloated behemoth.

With too many indistinctive products, Philips began to lose market share and rack up losses in the nineties. In 1996, the company was $ 300 million in the red – unsurprising when you consider that Philips employed 110,000 more people than Sony but earned 14% less revenue that year. There is a silver lining for Philips though, as one of its many forays into diversification – healthcare – may pave the way for its comeback.

In the Sri Lankan market, constrained by decades of war, vertical diversification was the most popular way forward for conglomerates in the past. However, with more specialised foreign enterprises now being added to the competitor mix, over-stretched conglomerates cannot hope to thrive without identifying a core differentiating proposition. Reinventing can no longer simply mean entering any fast-growing industry. Growing and transforming the core business successfully over time requires careful strategic consideration of logical and reinforcing adjacencies (see Diagram 3).

Ambidexterity

Given all the complexities of running and reinventing a business, how then does management strike a good balance? The answer is, as a good economist would say, “It depends”. It depends on the nature of the company, the dynamics of the market, and timing. While market forces will be beyond a single enterprise’s control, organisational changes and timing can be addressed through a well-crafted strategy plan.

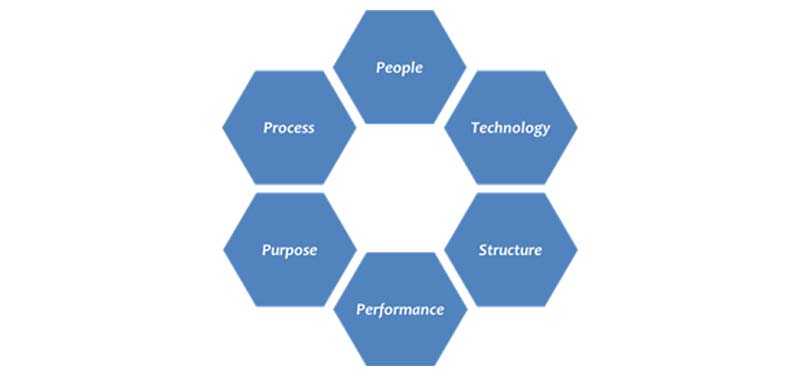

In any strategy plan, especially one that addresses the balance of exploitation vs. exploration, there are six crucial areas to address (see Diagram 4):

1. People and skills: HR models will need to be revamped so that people with varying skillsets can be assessed. While select highly motivated employees may be able to wear both hats (running and reinventing), HR will likely need to actively recruit, train, and develop two very different kinds of employees.

2. Technology and tools: New systems and tracking tools may be necessary to enforce and track implementation of strategic ideas. With timing being crucial for many innovative ideas, companies should explore options that allow fast kick-off, even if that means using transitional tools that can be upgraded later.

3. Governance and structure: This is one of the most challenging areas to address, especially in older enterprises. Being ambidextrous will require an organisation to be agile and have quicker decision-making processes – perhaps necessitating not just one major structural shakeup but constant evaluation and improvement.

4. Individual and enterprise performance management: More often than not, Management will need to set better KPIs to strike a balance. Executives are usually rewarded for profit, which results in exploiting behaviour being exalted over explorative action. While such an imbalance exists, a company cannot work toward ambidexterity.

5. Purpose and culture: Organisations that are unified by a common purpose and encourage a culture of ambidexterity are more likely to be sustainable. While this is considered an ‘intangible’ that hard-nosed businesses may not include in their strategic plans, there is ample evidence of purpose-driven companies achieving disproportionate success due to the revitalising energy a core purpose provides.

6. Processes and methods: Most organisations will have excellent processes already in place for running the core business but not for innovation efforts. Project management processes and methods are needed to make sure that the R&D aspects of a business are also run to fair but meticulous standards. To become a truly ambidextrous organisation, the processes and methods for both sides of the business must connect at critical points.

What is increasingly clear is that no company can now avoid addressing the need for ambidexterity. For those in top management positions, it is perhaps the single most important strategic course you need to consider, as nothing less than the future of your company depends on it.

(Sanda Wijeratne is a Manager at STAX Colombo and is the Delivery Lead of its Strategy Practice. STAX, Sri Lanka's leading management consulting firm, has its headquarters in Boston and branch offices across Chicago, Colombo, New York, and Singapore. With an end-to-end strategy offering, STAX works with clients to not only formulate a data-driven strategy roadmap, but also to execute that plan effectively. You can find out more at www.stax.com.)