Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Monday, 4 March 2019 00:05 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Olivia Ramya Tanner travelled to Sri Lanka to find her birth mother. Then the Swiss woman discovered that everything — from her birth certificate on up — was a lie. She’s not alone.

amp.dw.com: Having booked her dream vacation to Sri Lanka, complete with an Ayurvedic retreat, Olivia Ramya Tanner, who grew up in a Zurich suburb, thought it might be fun to use the opportunity to find her birth mother.

This was back in April 2016. The Swiss woman, who works for an IT company, hired a private investigator to do some advance work. Tanner’s sister, Géraldine, who is five years younger and also adopted, joined the search for her own mother.

Two days before they departed, the PI called. He had found Géraldine’s mother. A reunion was arranged. He couldn’t find any information on Tanner’s birth mother, though, so Tanner decided to stop by Ratnapura General Hospital, where she was born, to see what she could find out.

That’s when she learned her birth certificate was a fake.

“They told me I wasn’t registered there and that the birth certificate wasn’t even real,” said Tanner. “I was numb.”

A search of local and national records also turned up empty. It felt like she didn’t exist, Tanner said. It made her wonder: was her birthdate made up too? She was confronted with the strong possibility that even her middle name, Ramya, was a lie.

“The only thing I had that connected me to my mother was the name she had given me at birth. Turns out, it’s very likely she didn’t give me that name. So, I lost the ground under my feet,” she said. “My whole identity just crumbled… It was quite devastating.”

A year later, when Dutch television ran an investigation, Tanner discovered she wasn’t the only adoptee to have falsified papers. Now, a report issued by the Swiss Canton of St. Gallen confirms Tanner’s ugly discovery: Possibly up to 70% of the 750 adoptions of Sri Lankan children to Switzerland from the late 1970’s to the 1990’s were illegal. The question still unanswered in the report is why, in spite of warnings from the then-Swiss Ambassador and press reports in Sri Lanka, Switzerland and other European countries, they were allowed to continue for so long.

Children made for export

Probably 11,000 babies were adopted throughout Europe, the US and Canada from Sri Lanka in that timeframe. Some Sri Lankan mothers were told by corrupt hospital officials their babies had died during childbirth. Others were informed their new-borns needed special care, but instead were whisked away for adoption.

Many mothers were pregnant out of wedlock and had fled their villages to give birth. Fixers working for shady adoption lawyers scoured slums, train stations and hospitals to find these vulnerable women, forcing them to sign away their babies, the report said.

While official charities worked with orphanages and assisted with orderly, legal adoptions, many babies given up were often ‘ordered’ and produced within nine months, possibly at baby farms, for money. “These children were all made for export,” the report said.

Elisabeth Froelich, head of family and social services in St. Gallen, said the report is the first to be published, but that other cantons will also conduct investigations. A final, federal report is due in a year. St. Gallen’s report was the most important, however, because Alice Honegger, intermediary of Switzerland’s largest adoption service, worked from there.

The report could not conclude definitively that Honegger, who died in 1996, participated in illegal and lucrative activities. The report estimates she made up to $ 97,000 (€ 85,000) in one year alone from adoptions.

Tanner’s sister’s legal adoption was arranged by Honegger. But Honegger also organised the adoption of Sarah Ramani Ineichen in 1981. Her papers, too, were faked.

Ineichen, now a midwife in Geneva, says in spite of intensive searches and three trips to Sri Lanka, she doesn’t know where or when she was born. DNA testing proved that the woman who stood in court during adoption proceedings as ‘acting mother’ was not her biological mother.

“I have no further leads that could help me in my search and I have no information regarding the circumstances of my adoption,” Ineichen wrote.

After the Dutch TV report, the two Swiss women formed Back to the Roots, a group whose mission is to lobby the Swiss Government to find out what happened and to assist other Swiss adoptees in finding their biological parents.

Tanner’s papers were arranged by a well-connected Sri Lankan named Dawn da Silva, who contacted Tanner’s parents after they filed an adoption request at the consulate in Geneva. Da Silva, it turns out, referred to herself as a travel agent who arranged hotels, tours — and adoptions, according to the report.

Tanner met da Silva, who now is in her 80’s, when the Swiss travelled to Colombo in 2018. Da Silva could not be reached for comment.

“She thinks she did a good thing. That was the hardest for me to hear. That she didn’t have any regrets,” Tanner said. “She was very clear that she had nothing to do with (illegal adoptions). She was very generous in blaming other people. Like she had suppliers who brought the babies. That’s how she phrased it.”

Everyone shirked their responsibilities

Swiss officials did briefly revoke Honegger’s permit to provide adoption services. It was reinstated after an Interpol investigation found no evidence she had broken any laws and after Honegger received a permit from the Sri Lankan Government. The current Health Minister of Sri Lanka has now admitted to severe wrongdoing in the 1980’s and 90’s.

“In the summer 1982, in spite of the discovery of child trafficking in Sri Lanka, and in spite of the knowledge that Alice Honegger was the centre of activity for the mediation of children to Swiss couples in Colombo, canton officials were concerned not with stopping foreign adoptions, rather to make it appear that the procedures looked legal,” the report said.

Froelich agreed with the assessment. “There was no one single authority who could say ‘no more adoptions from Sri Lanka are allowed’. Everyone pushed away the responsibility.”

The feeling at the time was that as long as the children were placed with loving parents everything was fine. “The image of the couple rescuing children from what we then called Third World countries was seen by society as doing something good for the child,” Froelich said.

But for Tanner, it wasn’t fine.

The trouble was, Tanner believes, that international adoption was a business. “Demand controls supply. Obviously babies had to be organised for all these parents who wanted a new-born child, not the 4-year-old who has been in a foster home. So they say, ‘let’s take them from their mothers’.”

Swiss and Sri Lankan

DNA testing has proved to be the most effective way to connect adoptees with birth parents; and Tanner has discovered that many mothers in Sri Lanka are also searching for their lost children, women desperate to know the babies they gave up more than 30 years ago are okay.

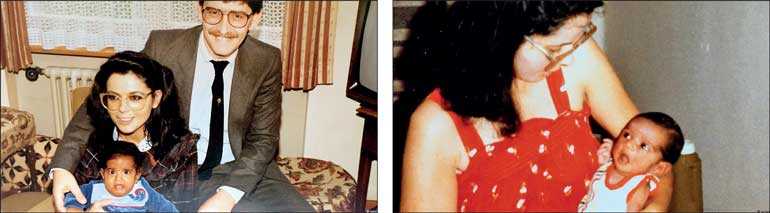

Tanner says that despite the loving care of her adoptive parents she feels a strong Sri Lankan identity

Tanner’s parents were stunned to learn her papers had been falsified. “My father was devastated. He had the best intentions,” she said. Now, she adds, her parents are proud she is working things out.

Having spent her life in Switzerland, Tanner said she used to feel “120% Swiss”. Still, when she went back to Sri Lanka as an adult, she said it felt right. She looked like everyone else. The food was right for her body. The people and climate were welcoming.

She loves her parents and sister, she said, but she has a nagging feeling. “I was made to lead a life there. To take me away was wrong.”