Wednesday Feb 18, 2026

Wednesday Feb 18, 2026

Saturday, 11 May 2019 00:01 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

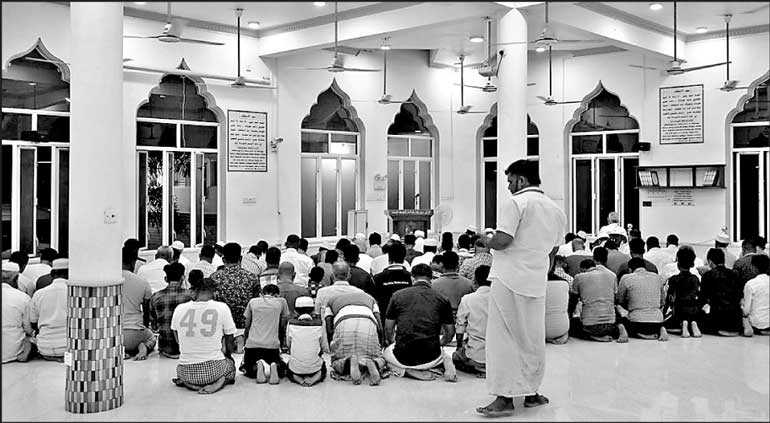

Muslims pray inside a mosque in Kattankudy, Sri Lanka, May 4, 2019 - REUTERS

RATHMALYAYA, Sri Lanka (Reuters): N.K. Masliya says she has been visiting a neighbourhood clinic in the north-western Sri Lankan village of Rathmalyaya for over five years, always dressed in a black abaya – a cloak-like over-garment worn by some Muslim women.

But when Masliya went to the clinic nearly three weeks after Islamic militants killed over 250 people in churches and hotels across the country, she said things had changed.

The 36-year-old said she was in a queue with her five-year-old daughter when a nurse told her to remove her abaya, saying: “What if you blow us up with your bomb?”

Muslim groups say they have received dozens of complaints from across Sri Lanka about people from the community being harassed at workplaces, including government offices, hospitals and in public transport since the Easter Sunday attacks.

The Government has blamed the attacks on two little-known radical Islamic groups. Islamic State has claimed responsibility.

In the city of Negombo, where over 100 people were killed at the St. Sebastian’s Church during Easter prayers, many Pakistani refugees said they fled after threats of revenge from locals.

Now, anger against Muslims seems to be spreading. On Sunday, a violent clash erupted between local Muslims and Christians after a traffic dispute.

“The suspicion towards them (Muslims) can grow and there can be localised attacks,” said Jehan Perera of non-partisan advocacy group, the National Peace Council. “That would be the danger.”

A ban on facial veils and house-to-house searches by security forces in Muslim-majority neighbourhoods across the country have added to the distrust.

The Government says it is aware of tensions between communities and is closely monitoring the situation.

“The Government is consciously in dialogue with all the religious leaders and the community leaders,” Nalaka Kaluwewa, Sri Lanka’s director general of information, told Reuters, adding that security has been increased across the country to avoid any communal tensions.

Buddhist hardliners

Muslims make up nearly 10% of Sri Lanka’s population of 22 million, which is predominantly Buddhist. The Indian Ocean island was torn for decades by a civil war between separatists from the mostly Hindu Tamil minority and the Sinhala Buddhist-dominated government.

The Government stamped out the rebellion about 10 years ago.

In recent years, Buddhist hardliners, led by the Bodu Bala Sena (BBS) or ‘Buddhist Power Force’, have stoked hostility against Muslims, saying influences from the Middle East had made Sri Lanka’s Muslims more conservative and isolated.

Last year, scores of Muslim mosques, homes and businesses were destroyed as Buddhist mobs ran amok for three days in Kandy, the central highlands district previously known for its diversity and tolerance.

The violence in Kandy was triggered by an attack on a Buddhist truck driver by four Muslim men after a traffic dispute. The driver later died from the injuries.BBS’ chief executive Dilantha Vithanage said as successive Sri Lankan governments had failed to address what he called a rise in Islamic extremism, Sri Lankans might be forced to do it on their own.“This is a bigger danger than Tamil separatism,” Vithanage told Reuters.

Sri Lanka’s junior defence minister, Ruwan Wijewardene, told Reuters the government was taking measures to curb radicalisation but conceded that communal tensions were a big concern.

Boycotting businesses

In Batticaloa, an eastern city home mainly to Christians and Hindus and where a bomber from a neighbouring town attacked an evangelical church on Easter, a Tamil group has called for a boycott of Muslim-run businesses.

The alleged ringleader of the Easter attacks, preacher Zahran Hashim, and the bomber who targeted Zion Church in Batticaloa were natives of neighbouring Kattankudy, a Muslim-dominated town.

“If you have any dignity, stop buying from Muslim shops,” read a red-inked leaflet distributed in Batticaloa and produced by a group called ‘Tamil Youth, Eastern Province’.

Two members of the group, who both said had lost relatives in the blast, told Reuters that resentment had been building for years against the people of Kattankudy.

“They have always been hostile towards us. They do not eat from our places. If they are going to grow by insulating themselves, we might as well too,” one of them said, speaking on condition of anonymity.Business has plummeted at the around 250 Muslim-owned stores in Batticaloa and some will be forced to shut unless sales pick up, said Mohamed Kaleel, the vice-president of the Batticaloa Traders Association.

Prior warnings

Among many Muslims, resentment is also building because they believe the community is being unfairly targeted, even though the government was warned repeatedly about possible attacks.

The government has said it had received prior warnings about impending attacks on churches but these were not shared across agencies and admitted that was a lapse.

Muslim community leaders have also said they had repeatedly warned the authorities about Zahran, the alleged mastermind, for years.

“The Government knew about the bombings and yet they didn’t take any action. But once it happened, they are targeting us innocent people. This is not fair,” said Milhan, a resident in the north-western town of Puttalam.

Abdullah, a Muslim preacher in Puttalam who declined to give his full name, said the discrimination will alienate Muslims and make them more vulnerable.

“By doing this, extremism will only increase, it won’t go away. This is what happened with the Tamils,” he said.