Saturday Feb 21, 2026

Saturday Feb 21, 2026

Saturday, 7 October 2017 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

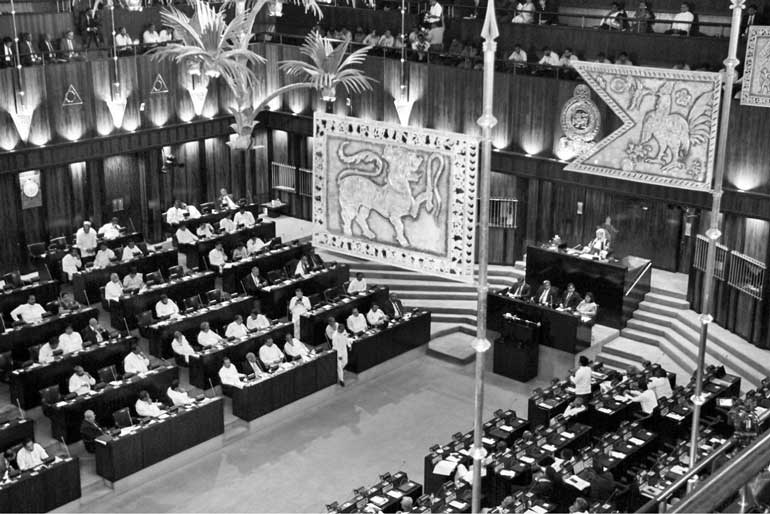

AP: As lawmakers in Sri Lanka celebrate the 70th anniversary of one of the oldest parliamentary democracies in Asia, minorities including Tamils, Christians and Muslims remain on the fringes of society.

AP: As lawmakers in Sri Lanka celebrate the 70th anniversary of one of the oldest parliamentary democracies in Asia, minorities including Tamils, Christians and Muslims remain on the fringes of society.

They have some representation in Parliament but say they are sidelined by Buddhist Sinhalese, who are the majority in the country and control the legislature. It has done little to heal the wounds from a quarter-century civil war that ended in 2009 and still refuses to acknowledge or investigate allegations of wartime atrocities.

The legislature has been accused of perpetuating rule by the Sinhalese, who are 70% of the population, instead of unifying the multicultural nation.

With tensions growing, some, including the prime minister, have questioned whether Sri Lanka has been successful in building a nation.

“We started 1947 as a united people, but over the past years we had an ethnic conflict ... to the point of a civil war,” Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe told a special session of Parliament on Tuesday to celebrate its 70th anniversary.

“We safeguarded democracy through all that, but we are yet to provide a political solution and unify the country,” he said.

Others say that, while democracy has helped Sri Lanka on many fronts, it has also harmed. Jehan Perera of the National Peace Council, a research and activist group, argues the political system has increased divisions.

“In a country of ethnic divisions, majority rule can be a dictatorship by a permanent majority over a permanent minority,” he said.

The divisions surfaced quickly after the tropical island nation then known as Ceylon won independence from British rule in 1948.

Within two years, the first post-independence Parliament stripped hundreds of thousands of mostly Tamil tea plantation workers of Indian origin of their citizenship and right to vote. That prompted fears among indigenous Tamil leaders, who demanded a federal form of self-rule in the country’s north and east where they form a majority.

In 1956 a new government came to power on a wave of Sinhalese Buddhist nationalism and quickly abolished English as the language of government, instituting Sinhala as the only national language. That marked the starting point of an ethnic conflict that later flared into a vicious civil war that killed at least 100,000 people, according to UN estimates.

Non-violent campaigns by Tamil leaders demanding equal status for minority Tamils were attacked, and anti-Tamil riots killed hundreds of people. Thousands of other Tamils fled the country.

A cry for an independent Tamil state soon strengthened, and from the early 1970s Tamil youths in the north and east began taking up arms and launching sporadic attacks on police and government installations. Tamil politicians, meanwhile, boycotted discussions on crafting the first constitution because they said their concerns were not considered by the Parliament at the time.

It wasn’t until state-backed Sinhalese mobs launched countrywide riots and attacks against Tamils in 1983 that civil war erupted in earnest. The riots left Tamil villages burned and hundreds dead. Hundreds of thousands fled the country, while many of those who remained joined Tamil militant groups.

Faced with a bloody conflict, Parliament attempted several constitutional changes to share some power with the Tamil minority and nullify the call for separatism. It introduced provincial councils through an India-brokered peace accord in 1987.

But the councils fell short of Tamil demands for autonomy, and Sinhalese opposed them for giving too much power to the minority group.

Parliament had also changed its stand on the language issue and included Tamil as an official language, but statelessness and voting rights of plantation workers of Indian origin weren’t fully settled until the early 2000s.

“There is no reason to be proud of our parliamentary democracy, it has been a failure,” said senior Tamil journalist Veeragathy Thanabalasingham.

“As early as 1948 the government started enacting laws to suppress minorities. As a result, a war erupted. Even after such destruction, the Sinhala polity has not had a change of mind in order to prevent more conflicts in the future,” he said.

The war ended in 2009 after Sri Lankan soldiers killed the leader of the Tamil Tiger rebels, and many hoped that would lead to a period of post-war reconciliation and a resolution of widespread war crimes allegedly perpetrated by both sides.

But no independent investigations have been allowed. Meanwhile, the military remains powerful, occupying barracks lined with barbed wire and private lands across the former conflict zone. Efforts to reform Sri Lanka’s police, judiciary and other institutions to reflect the country’s ethnic composition have crawled, exacerbating minority fears.

Last year, Parliament passed a proposal by Wickremesinghe to begin writing a new constitution to provide more minority rights and power sharing. However, the drafting has been delayed by political divisions and opposition from influential Buddhist monks.

Any proposed new constitution would have to be passed by a two-thirds majority in the Sinhalese-controlled Parliament and then be approved in a public referendum.

Meanwhile, Parliament remains far from achieving a consensus on how to deal with the allegations of wartime atrocities and human rights abuses – both efforts that draw strong protests from Sinhalese nationalists.

There are also divisions between the two main parliamentary parties that have formed a unity government, with Wickremesinghe’s group pushing reforms while President Maithripala Sirisena’s party has been more circumspect.

The patience of Tamil leaders has been dwindling.

“We have all learned many lessons from the most harmful situations that have prevailed in our country,” said Rajavarothayam Sampanthan, an opposition leader in Parliament and the main Tamil leader.

“It would be a tragedy if in the name of patriotism, more exactly pseudo patriotism, anyone seeks to prolong these harmful situations.”