Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Monday, 2 October 2017 00:03 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By D.C. Ranatunga

A special sitting of Parliament will be held on Tuesday, 3 October to commemorate the 70th anniversary of parliamentary democracy in Sri Lanka.

After accepting the Westminster model of parliamentary system of government recommended by the Soulbury Commission, the first Parliament had its inaugural meeting on 14 October 1947. Governor Sir Monk Mason Moore, representing the monarch of England (Ceylon was then a British Crown Colony) delivered the Throne Speech outlining the government’s plans in the period to follow.

In the bicameral legislature, the House of Representatives (the lower house generally referred to as Parliament) sat the Gale Face building which was earlier the venue of the State Council and the Legislative Council. The Senate, the upper house was housed in what came to be known as Senate Square in Fort opposite Gordon Gardens adjacent to Queen’s House, present President’s House.

Seating arrangements had to be adjusted for the government MPs to sit on the right of the Speaker and the opposition MPs on his left. Earlier the seating was in a semi-circular setting.

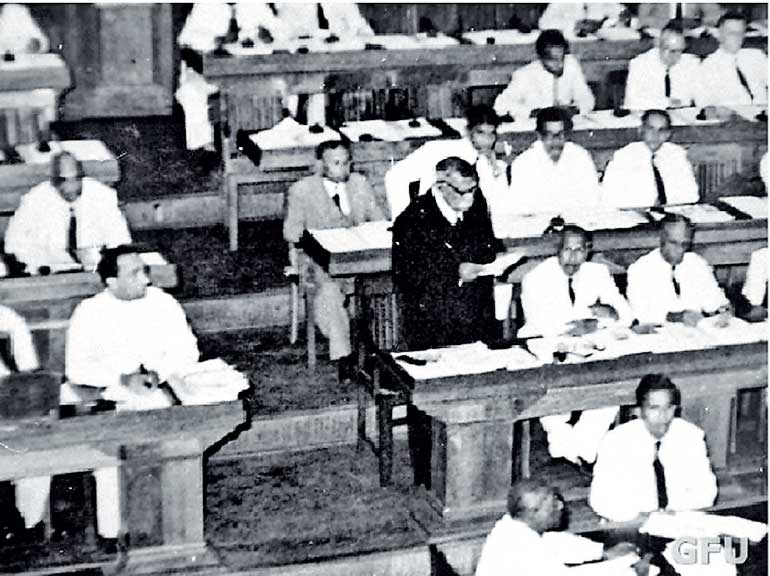

First Prime Minister D.S. Senanayake addresses the first Parliament

The first Parliament had 101 members (MPs), 95 being elected by the people and the balance six nominated by the governor. A limited number of members of the public could watch the proceedings from the public gallery situated in the first floor. A separate VIP gallery, also in the first floor, facing the Speaker was limited for the diplomatic corps, foreign visitors and local VIPs. Media was accommodated in the Press Box in a corner adjoining the seats of the Opposition members. Right opposite where the government MPs sat was the Official’s Box where public officials who had to brie the ministers during debates sat.

Parliament was considered ‘sacrosanct territory’ with the public maintaining silence and making the least possible noise while getting about inside the premises. The first occasion when there was a big commotion was just before the opening of the Third Parliament in April 1956 with the dawn of a new era following the victory of the Mahajana Eksath Peramuna led by S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike when the governing party was reduced to a mere eight seats with Prime Minister Sir John Kotelawela (Dodangaslanda seat) and M.D. Banda (Maturata) being the only ministers out of 12 who contested, were returned.

The public stormed the House in large numbers and ‘invaded’ the Speaker’s chair and, if I remember right, one them sat on it. Referring to the incident, former Secretary General of Parliament, Sam Wijesinha, writes: “Mr. Bandaranaike said, when his supporters were pouring into Parliament and breaking chairs and destroying some of the furniture, that this was a people’s government (‘Ape Aanduwa’). So the people had the right to destroy their own furniture if they wanted.” (‘All Experience’ 2001)

A month or so later I joined the Dinamina as a reporter and started covering Parliament as part of my work. I felt I was back in the university. The speeches made by Prime Minister Bandaranaike and Ministers Philip Gunawardena, W. Dahanayake and T B Ilangaratne, Opposition stalwarts Dr. N.M. Perera, Dr. Colvin R. de Silva, Bernard Soysa, Dr. S.A. Wickremasinghe, Pieter Keuneman, S.J.V. Chelvanayagam among many others were a treat to listen to. They always studied a subject thoroughly before participating in a debate. The subject matter was so meaningful. Criticism was so constructive.

Sinhala Only bill

The first major debate I covered was the Sinhala Only bill in June 1956 making Sinhala the official language of the country. Bandaranaike was fulfilling the key election promise and there was wide interest in the country on the debate in Parliament.

At least four of us covered the proceedings each one taking turns, writing the copy based on the notes we took down, carefully going through what we wrote and dispatching to office through the peons who stood by to rush with the copy for the early editions of the paper which were sent to the outstations.

With no television and with the state radio channel (only one at the time) giving a short resume, people waited for the morning newspapers (also limited to two Sinhala, two Tamil and two English papers) to read a lengthy report. The debate which started at 2 p.m. went till about 9 p.m. during the allotted days.

The final night when the voting was to take place was eagerly looked forward to. I finished my shift early and went home. When I got back to office the following morning, there was pandemonium. We had made a huge mistake in our report on the final stages of the debate.

To make matters worse, the mistake was in the speech on Prime Minister Bandaranaike winding up the debate. We had reported that the Prime Minister had said that there was no difference between Sinhala Only and parity of status to Sinhala and Tamil promoted by leftist parties.

The night sub-editor had used it as the headline in the middle page with the report of parliamentary proceedings. My colleague who had written the copy had obviously realised the grave mistake he had made, come to office early in the morning, left his resignation letter and vanished.

The Prime Minister had telephoned the Managing Director Esmund Wickremasinghe and accused him that this was a deliberate act of sabotage on the part of Lake House. I was to do the first round of coverage that afternoon and my editor warned me that I would have to face a barrage of unkind words blaming the Dinamina and Lake House. I had no choice. When the Prime Minister started to speak all eyes were on the press box. I kept my face down and took down the notes.

There was a profound apology on the front page of the next day’s Dinamina and the PM’s speech was carried in full. An unforgettable day in my coverage of Parliament.

After the Sinhala Only Act there were several other far reaching legislation passed in Parliament. Of much interest were the nationalisation of bus services, the establishment of the Employees’ Provident Fund, and the granting of security to the farmer through the Paddy Lands Act.

MP carried out

I remember one incident when a Member of Parliament was bodily carried out for refusing to leave the House on the orders of the Speaker. C Suntheralingam, one time Professor of Mathematics who resigned to enter politics and represented the Vavuniya seat in Parliament continued to speak when the Speaker ordered him to stop when he exceeded the time allotted to him.

The Sergeant-at-Arms, the chief security officer in Parliament, was asked to remove the MP. When he was carried out the MP insisted on taking his papers with him. He asked the Police to leave him on the pavement near the entrance to Parliament where he squatted and spoke to the newspaper reporters.

Another memorable night was when the Dudley Senanayake Government was defeated at the voting on the Speech from the Throne on 30 March 1960. With no party gaining a clear majority at the March 1960 general election, the UNP which had 50 seats as against SLFP 46, was invited to form the government.

With the election of the Speaker from the Opposition – T.B. Subasinghe 93 votes as against 60 by the government nominee Sir Albert F. Peiris – it was clear that it would be difficult for the government to carry on. An amendment to the Throne Speech proposed by the Opposition that “the House does not have confidence in His Majesty’s Government” was carried by 86 to 61 votes and the Prime Minister advised Governor General Sir Oliver Goonetilleke to dissolve Parliament. Thus the Fourth Parliament became the shortest in the country’s parliamentary history – 30 March – 23 April 1960.

In the general election that followed in July 1960, Sri Lanka created history by electing the first woman Prime Minister in the world. That’s another story.