Sunday Feb 22, 2026

Sunday Feb 22, 2026

Monday, 13 December 2021 03:42 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Kamini Rathnayake

The day of 21 April 2019 is a traumatising reawakening of the decades-long civil war that Sri Lanka experienced. One may even regard the recent experience as more daunting, as the horror of it still lingers. Almost three years and six volumes of a commission report later, one is left to wonder – have the victim-survivors got justice?

Memorialisation – What do women want?

A reverend sister attached to a convent in Bolawalana, Negombo who is well known and respected for her service to the community illustrates the need to heal from such incidents: “When we talk about recovery, we need to look at this the same way as a physical wound. In a physical wound, if we do not clean and put the medicine, it can get infected and later can even turn into cancer.”

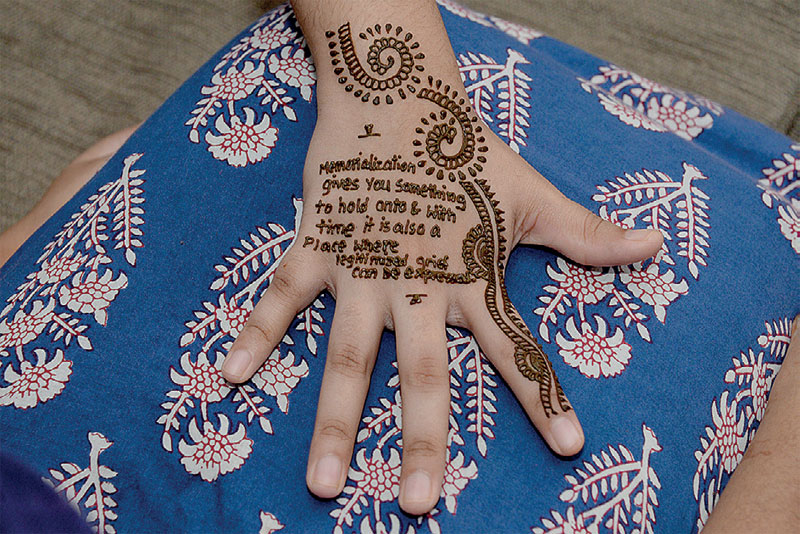

‘Memorialisation’ appears to be jargon only understood by those who are either interested or invested in the field. However, a conversation with the grassroots will prove the opposite. While this may not be the term used by them, it is what they yearn for; to remember their lost loved ones, to commemorate them and to ensure a lesson is learnt and the same is not repeated.

“They [victim-survivors] seem to have gotten motivated to make sure that the lives of their loved ones were not taken in vain. They want people to know what happened, they want society to remember the incident, they want to stop anything like this from happening in the future and to that end they want anyone and everyone in positions of power to address the root causes,” says a leader of a civil society organisation dedicated to serve the victim survivors of the Easter Sunday attacks.

When asked about the expectations of women from memorialisation, a counsellor responds: “In all the houses there are photographs of those who died. It is more important for the entire society to have a reminder that a terrible event like this should not happen again,” voicing the victim-survivors’ hopes of healing and reconciling through memorialisation.

While discussing the importance of memorialisation to prevent the recurrence of such violence, a psychiatrist mentions, “Memorialisation is part of prevention of violence. If we forget what happened, then the possibility of recurrence is much higher. People will not remember the individual trauma and the collective trauma that people had to endure.”

Memorialisation at an individual level

A psychosocial practitioner who works with female victim survivors of the Easter attacks believes that “memorialisation is a way of remembering the person you have lost, it is a way of capturing not just the memories, but also capturing the meaning of that person’s life”.

Explaining what ‘meaningful’ memorialisation is, she states: “It is not just wanting to remember in photographs and memories or incidents, but to capture, in some way, what this person contributed to the community and remember what the person could have contributed as well.”

She goes on to describe a woman who had turned her life around to dedicate it to find purpose for her lost family. She recalls: “She started to say, ‘I must give voice to what my children and husband did in this world. I can’t just let my family die without a purpose, I must let the world know about who they were and what they did. They cannot just be a picture on the wall. These are real people and people must know the kind of husband he was, and the kind of daughter and son they were to me.’”

Another psychosocial practitioner who works with those who survived the attack describes the experiences of a female victim-survivor who lost her entire family. She further explains how the victim-survivor needed to remember her loved ones in a manner that brings value to their existence in the community:

“For instance, they [victim-survivors] want to share that these people were of ‘such capacities,’ ‘with such good qualities,’ ‘they lived life like this’ and for families to continue remembering how academically successful the children were. Moreover, they wanted to share how well brought up the children were and to ensure the children’s identities were not lost.”

Memorialisation without blame games

Moreover, she points out an important aspect to memorialisation: “Memorialisation needs to happen without playing the blame game. I think it is important for organisers of these events [media/press briefings] to acknowledge the loss but not make use of it.”

Especially in similar incidents to this, where the context is very much political in nature, it is paramount that these vulnerabilities of victim survivors, especially those of women, are not misinterpreted, misrepresented or misused, by the communities, political parties, and media or by the society at large.

A reverend sister mentions, “There were times where they [victim-survivors] did not want to talk to the politicians and media personnel. They rejected being filmed because they often feel used and misrepresented by the media and the politicians.”

All interviewees, who have first-hand experience of working with these victim-survivors, reiterate one point on the way in which the Church as an institution and the victim-survivors reacted to the incident.

A civil society organisation representative mentions, “They did not point fingers at anyone or blame anyone for what happened, they handled the situation very peacefully. This is not to say that they were not angry, but they knew how to handle their feelings in public,” contributing to initiate the recovery process and reinstate stability in the community post-incident.

In laying this foundation, memorialisation is pivotal for victim-survivors to first grieve and heal spiritually at an individual level, and then to move on to create a space for community level healing. This leads to unity and togetherness within and among the communities, because according to an interviewee who is a psychosocial practitioner, “Healing has so many different layers and aspects to it.”

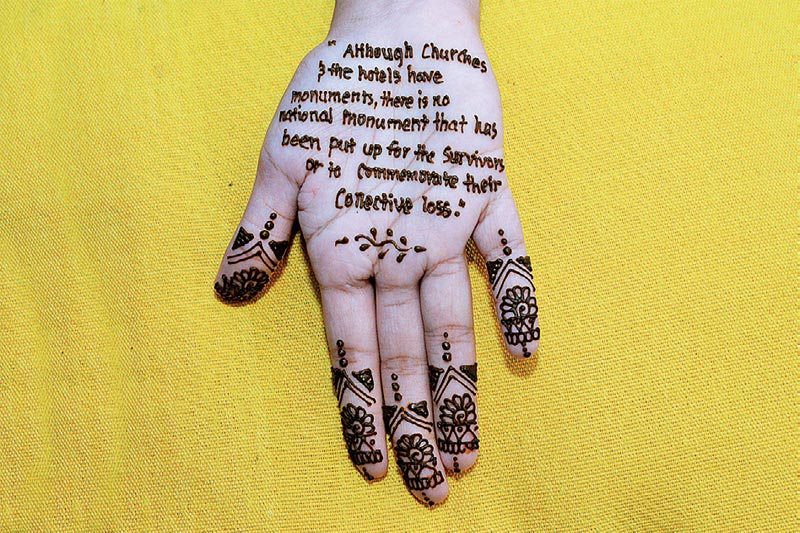

Memorialisation at a community level

“The community has to offer [the] opportunity for them [victim-survivors] to make a public acknowledgement of the lost loved ones as this was a public tragedy,” says a psychosocial practitioner.

While emphasising the importance of public acknowledgement of the loss as a means of memorialisation, two interviewees recollect an event organised by the leadership of a reverend sister attached to a convent in Bolawalana, Negombo:

“They unveiled a sculpture with the photographs of all the children who lost their lives and organised scholarships for the children who lost their parents from the attack. It was organised so that a parent who lost a child was accompanied by a child who lost a parent. The scholarships that were handed out were in the name of the children who lost their lives. This is important because these parents are never going to see their children’s graduation or wedding. So, this was the event that would stay in their memory in a very positive way. Although they were grieving, it was organised in such a way that it also celebrated the strengths of the children who lost their lives. This event is a positive memory that the parents and the closest friends of the child victims can keep coming back to in the future.”

A doctor, in his experience, believes: “[When] trauma has taken place in a large group of people, having group memorialisation allows them to share their grief and loss. This sharing of grief creates a bond due to the similarity in experience, and this creates unity.”

They mentioned how they came across certain affected women who would “...not leave the house unless it was for the weekly group therapy session,” proving how effective and helpful group memorialisation is for these victim survivors.

A reverend sister conveys the wishes of women they had worked with, stating: “So from all this I can emphasise on the importance of developing support groups as a form of memorialisation. This will not only help those who survived the attack overcome their pain but also create inter-ethnic conversation that will enable understanding of these different communities,” connecting it to the bigger picture.

Reparations – Means of livelihood support to move forward

As a subsequent step to meaningful memorialisation, rebuilding their lives and regaining the ability to lead an ‘ordinary’ life begins with reparations. A psychosocial practitioner believes, “After the immediate stages of grief subside, people’s lives change and then there should be support for that, both legal and economic.”

In this attempt, according to the interviewees, the most common issue encountered by women who had lost the breadwinner of the family is the lack of physical proof of qualifications to get re-employed. Explaining the situation of one woman she has interacted with, a psychosocial practitioner says: “Initially [she] was struggling to find employment partly because she does not have any paper qualifications. This was the case for many women as they did not have their skills on paper.”

An alarming aspect of women receiving compensation as reparations was also highlighted by the same psychosocial practitioner. She says: “Another reverend sister who was working with a larger group of female survivors in Katuwapitiya said that sometimes this money can be an issue because there are men getting close to these women and trying to marry them for the money. If you lost three or four family members, the women survivors received approximately Rs. 4 million. This amount of money attracted other men who are not genuinely interested in these women.”

This is in addition to the inconvenience they have to face from their in-laws, as pointed out by the interviewee. In instances where all family members were tragically lost and women had to legally share family property, there have been numerous situations where their vulnerability was exploited by the in-laws over previous disputes between them. Up to this extent, continuous psychological and psycho-social support were also highlighted by the interviewees as an essential form of reparation required and expected by these victim-survivors.

On the other hand, a reverend Sister attached to a non-governmental organisation says, “What the survivors continually say is that they need legal justice,” of knowing who is responsible, who were the perpetrators and why they were targeted, reverting to the initial position of this article, the requirements to heal and move forward.

All interviewees agreed upon one fact based on their interactions with the victim-survivors. This was further articulated by a leader of a civil society organisation which was dedicated to supporting the lives of victim-survivors: “If you ask the survivors which organisation should help them, they will say ‘the Government’. And if you ask which organisation has been helping them, they will say ‘only the church’.”

(The writer is an Intern at the Centre for Equality and Justice.)