Tuesday Feb 24, 2026

Tuesday Feb 24, 2026

Monday, 18 October 2021 02:28 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Centre for Equality and Justice Consultant Shalomi Daniel

Since time immemorial, chronicling memories have been second nature to human beings. Memories may be inspiring or debilitating, pleasant or painful – however, they are most importantly, powerful.

This is especially true in a post-war or post-conflict context, as memories play a vital role in facilitating healing and fostering greater understanding and empathy. However, women in such post-war or post-conflict situations often find that their memories go unacknowledged, and their voices are drowned in the cacophony of other voices – of powerful men and men on the battlefield, be it that of the victor or the vanquished.

“The act of remembering and memorialisation enables healing and closure. At a societal level, memories play the vital role of shaping a holistic narrative – by creating the space to voice alternate or lesser-known narratives” says Radhika Hettiarachchi, a development practitioner, researcher and curator with several years of experience in the area of peace building.

Going on to explain why it was important for these women to share their stories, Hettiarachchi states: “A women-centred narrative is important. It shows the cost of war and the agency of women. It highlights their narratives as survivors, not just as victims.”

The stories and memories of these women, these unsung heroines, are a powerful reminder of the inherent strength of the human spirit in the face of adversity, and the futility of hatred and divisions. History books and newspaper accounts archive the names of battles won and lost, land gained and forfeited. However, it is the stories of these women that open our eyes to the anguish of losing loved ones, the fear for the lives of one’s children, and the extraordinary lengths that women would go to ensure the wellbeing of their families.

“I wouldn’t use these words. Just say ‘These stories go beyond facts and figures, to flesh out history with the lived experiences of real people. They bring to light the ordinary women who have lived through extraordinary experiences and have shown indomitable spirit and resilience’,” opines Hettiarachchi.

In the course of her work, Hettiarachchi has witnessed the courage and strength of such women from various parts of the island. One such initiative was the Community Women’s Workshops organised by the Centre for Equality and Justice, where women from different parts of the country and different ethnic and religious communities came together to share their experiences and memories.

These narratives, which are often not captured in the annals of history, are extremely important for several reasons. They detail the daily experiences and challenges of a country in turmoil or at war. At a time when both Sri Lanka and the world continue to grapple with a lack of understanding and empathy between various groups on myriad grounds, these stories are a stark reminder of the human cost of violence and war.

The act of remembering and acknowledging the plethora of emotions and memories from sorrow to anger to confusion, can prove to be a complex, and yet essential cathartic process. Such emotional healing and acknowledging of different narratives are quintessential to address root causes and unanswered questions; it is then that the mistakes of the past will not be repeated when forging a better tomorrow.

Hettiarachchi highlighted the importance of memory to bring about healing in post-conflict situations.

Speaking of the work done under the Community Women’s Workshops, she explains: “We worked with groups of women from different parts of the country, helping them to give voice to the stories that they held on to silently. By saying it out, by hearing similar stories to your own experiences from someone you thought was so different to you, the gap between the self and the other lessened. This was the start of empathy, healing and understanding.”

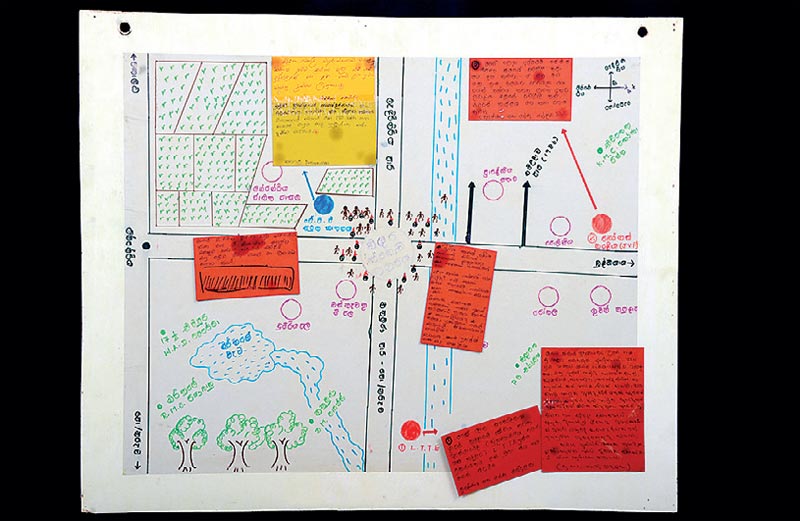

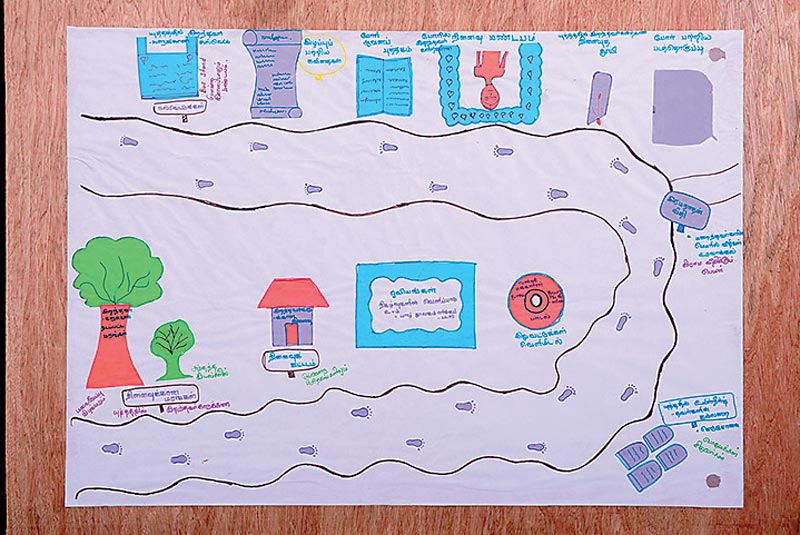

She went on to elaborate that the women were encouraged to bring an object that held potent memories for them and share their personal experiences and stories. Creative tools such as painting, poetry and drawing memory maps were employed to illustrate their memories. This proved to be a therapeutic process for the women, who were able to unburden themselves and share their pain and hurt with others; it was a process of being heard and understood.

“Nothing was about making accusations or assigning blame. It was more of sharing their personal experiences and lending a listening ear,” explains Hettiarachchi.

When asked if language was a barrier for the women to communicate with each other, Hettiarachchi explained that there was no need for an interpreter, as the women were able to communicate through their emotions and similar experiences, despite the language difference.

“They were able to empathise with each other and reach across the various divisions of ethnicity and religion” states Hettiarachchi.

Thus, this process paved the way to build bridges across ethnic and religious divides. The women were able to realise that though they hail from different ethnic and religious backgrounds, their experiences and the pain and hurt that had haunted them were similar. These memories are therefore essential in the reconciliation process, and help foster understanding at several levels – be it inter-religious, inter-ethnic, inter-regional or even intergenerational.

Understanding the need for such intergenerational conversations, the Centre for Equality and Justice facilitated Intergenerational Dialogues, bringing together youth and elders from various communities, and creating space for experiences to be shared and lessons to be learnt.

“Most of the younger participants came of age during the war, and their experiences differed from those of their elders,” says Hettiarachchi. Hence, these conversations proved to be an enriching learning experience, and a valuable exercise of nurturing understanding through oral histories and memories.

As Hettiarachchi points out, we practise private memorialisation, as cultural or religious practices, through remembering the dead at our shrines at home, almsgivings etc., but at the same time memorialisation at a community level is equally important. This is what enables stories to be shared across the divide, and to take cognisance of the pain and suffering on all sides.

“In creating such spaces for remembering as a community, it is important to ensure that these efforts highlight women’s voices, and that their narratives are unadulterated and original,” Hettiarachchi stated, adding, “We have to ensure that memorialisation is inclusive, and does not exacerbate the divide.”

Such endeavours require a united effort from both state and non-state actors, where joint ownership of such efforts is undertaken. This will ensure the continuity of those stories beyond the lifetime of its protagonists.

As the Centre for Equality and Justice states in ‘Women. Memory. Reconciliation’ [2019] “History, constructed not by privileged historians, but by these ordinary people who have experienced the pain themselves…” is indispensable to provide a multi-faceted portrait of past events for posterity.