Saturday Feb 21, 2026

Saturday Feb 21, 2026

Friday, 7 August 2020 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Md. Shahidul Haque and Sheikh Tanjeb Islam

Remittances serve as lifelines between migrant workers and their families back home, especially during a crisis. These money transfers provide efficient and effective safety nets to people living in the margins of economies.

Unfortunately, as a result of disruptions caused by COVID-19, the World Bank predicts that remittance flows will face their sharpest decline in history, falling by an expected 20% in 2020 to $445 billion. Understanding how remittances work best – and how the pandemic will shape them – can aid in charting a roadmap for hard-hit countries like those in South Asia.

Understanding COVID-19’s impact on remittances

Remittances are a key mechanism for boosting consumption in a migrant worker’s home country. In 66 countries, remittances account for more than 5% of GDP.

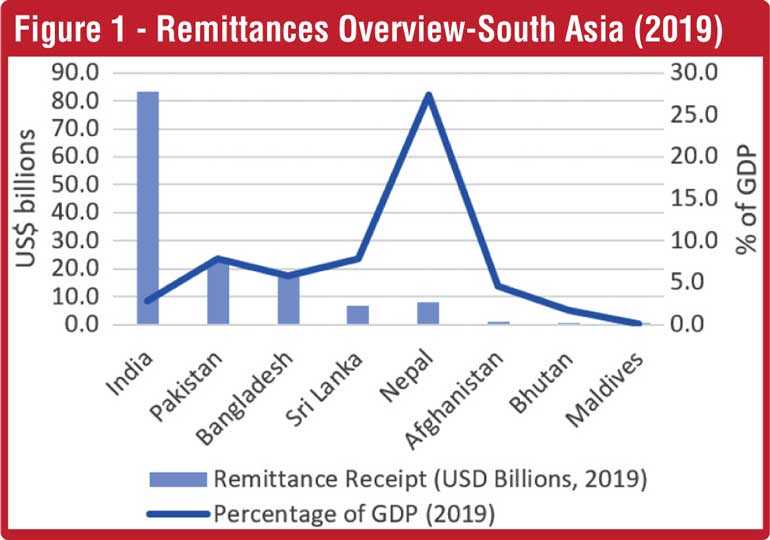

In South Asian economies, however, remittances play an even more important role in countries’ development roadmaps. India, for example, is the single largest remittance recipient country in the world, receiving more than $ 80 billion in remittances in 2019.

Across these South Asian economies, remittances comprise large shares of countries’ gross domestic product (GDP). For example, remittances account for nearly 28% of Nepal’s GDP and 8% of Pakistan’s.

While remittances can shape a country’s trajectory, they are highly dependent on three critical factors: economic opportunities in home countries; the international migration system; and the international financial system. The coronavirus pandemic has affected each of these three factors as it has created multifaceted human crises and disproportionately impacted the worlds’ most vulnerable populations.

Although past remittance flows have been relatively resilient to external shocks, COVID-19 is different. The pandemic has already severely affected the 272 million international migrants by reducing their main source of income and job security. As a result, it has reduced remittance flows causing households to lose an economic lifeline. In South Asia, it is projected that remittances will fall by more than 22% in 2020 (marginally above the global trend the World Bank has predicted) before recovering in 2021. Figures released by their respective central banks show that, year-on-year, remittances for the month of April fell by 25% in Bangladesh and 14% in Sri Lanka.

Prolonged economic recession will force the return of a significant number of migrants to their countries of origin, aggravating the economic downturn and social disruption and resulting in gender-based violence and societal tensions. The effect of the projected sharp decrease of remittances on households in South Asia can potentially push back decades of progress made by the region on poverty reduction, income inequality, nutrition, health and education.

Measures for action

As with other sectors, public-private cooperation will remain key in mitigating the impact of COVID-19 on the remittances industry. Considering the importance of the remittance industry in the region and within the framework of the Regional Action Group for South Asia of the World Economic Forum, a policy note was developed to support both the public and private sector to address this critical development challenge. It highlighted four immediate steps that stakeholders in South Asia need to take to arrest the decline of remittances in the region.

These steps complement the call to action which has been initiated by the Governments of Switzerland and the United Kingdom with strong support from multilateral institutions, such as the World Bank and United Nations Capital Development Fund.

1. Declare the provision of remittance services as an essential service to keep remittance service providers’ outlets open to the public

While banks and other financial services have remained open, there is a need to ensure that non-financial institutions that are also part of the ecosystem remain open – such as mobile operators, money transfer companies and post offices in both host and home countries. This will only be possible if countries declare remittances to be an essential service.

2. Provide fiscal and monetary incentives

Governments in the region have taken on an active role to roll out economic stimulus measures to cushion the domestic economy from the impact of COVID-19. Countries may consider providing 3%-5% cashback on certain corridors (e.g. high-volume corridors such as Middle East to South Asia) to waive transaction costs.

For example, for every $200 sent through a banking channel, $6-10 can be reimbursed in the bank account of the migrant/diaspora family member within 30 days. The ceiling for such transactions to receive the cashback incentive can be capped if necessary. Providing direct benefits to the end beneficiary also raises more awareness and opportunities for banking channels to be utilised for cross-selling opportunities. Bangladesh, with its 2% cashback, is a recent example from the region. This will ensure that remittances flow through the formal banking channel leading to higher volumes for the operators and help to increase the foreign exchange reserve for countries.

3. Include remittances in the broader migration debate

Countries in South Asia, through their diplomatic footprint, are working closely with host governments to address migration issues. However, policymakers need to take this one step further by also engaging in dialogue with a multi-stakeholder communities in host countries, which includes not just the government, but also the remittance service providers in the broader ecosystem. This may help to facilitate remittances through formal channels for South Asian expatriates with limited documentation, especially for low-value transactions. This could be done on humanitarian grounds and as a pilot for a period of six months at the least.

Remittances leverage primarily migrants’ private resources that they invest in building economic and social assets for their families and societies. These payments also assist in developing both the soft and hard assets for migrants and their families in their host countries. In South Asian countries which naturally lacks social safety nets, remittances provide much-needed financial security which, in turn, supports poverty alleviation. Despite the challenge thrown by COVID-19, there are many steps that both the public and private sector can take to help the ease the pressure felt by the migrants as they look to support their families in the home countries.

4. Reduce the average cost to achieve the United National Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) target

While the SDG target is stated for 2030, the pandemic offers the opportunity for South Asian countries to work with service providers as well as the host governments to achieve this target in the short term. This would require a fast adaption of technology products in both the host and home countries. Central banks in home countries should also look to ease know-your-customer (KYC) and regulatory requirements for both traditional service providers as well as fintech companies to help reduce the average cost.

The power of remittances lies in how they are invested by the families of migrant workers, helping them build up economic and social assets across generations. In South Asia, where social safety nets or weak or absent, remittances often form the bedrock of a family’s financial security, on which generational resilience to economic shocks is built. Blindsided by COVID-19, many families have already consumed their private safety net of saved up remittances and they now risk falling back into poverty. It’s time for both the public and private sectors to throw them a lifeline.

(Md. Shahidul Haque is Former Foreign Secretary of Bangladesh. Sheikh Tanjeb Islam is Community Lead, Asia Pacific & Global Leadership Fellow, World Economic Forum.)