Monday Feb 16, 2026

Monday Feb 16, 2026

Tuesday, 31 December 2019 00:15 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Malitha Goonaratne

The Fortune Business Insight estimated that the global blockchain technology market size is expected to reach $ 21,070 million by the end of 2025, with a compound annual growth rate of 38.4%, showing a promising start for the upcoming technology.

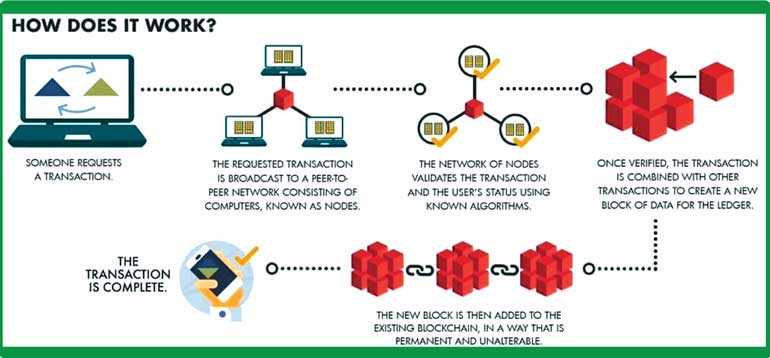

In a blockchain, transactions can be thought of as “blocks”, once verified by a network, are “chained” together with other “blocks”, and replicated on every system in a decentralised network to complete the transaction. This blog discusses the potential benefits and challenges in implementing blockchain technology for voting and the banking sector in Sri Lanka as well as data privacy concerns.

Benefits of using blockchain technology

The main advantages blockchain provide are its immutable ledger system, decentralised network, and transparency of transactions. The ledger system and the decentralised network do not allow for data alteration or deletion.

Data held in ledgers is encrypted cryptographically and transactions are replicated on every computer on the network. If one computer fails, the data is still backed up onto every other node on the network. This provides for higher data security over traditional, centralised data storage systems.

The transactions are recorded in chronological order; therefore, all blocks are time stamped. Authorised persons can view transactions and track the origin of any ledger without depending on third-parties, providing greater transparency for a system using blockchain.

Benefits and challenges of implementing blockchain technology in the banking sector

An application of blockchain technology falls in the financial sector, coined under the term ‘FinTech’. Last year, the Central Bank of Sri Lanka (CBSL) appointed two committees on FinTech and blockchain to bolster technological progress in the financial sector.

Sampath Bank was Sri Lanka’s first bank to initiate a blockchain-based banking solution through the launch of ‘igift’, a person to person gifting mobile app. This allows for an individual having a Sampath bank account to gift money to anyone in their smartphone contact list, facilitating another medium to transfer funds over traditional bank transfers.

Similarly, Commercial Bank utilises blockchain technology for remittances. This ensures that the transfer is transparent and tamper–proof, and allows for more accurate tracking of remittances. HSBC has also joined the fray by launching a web-based supply chain platform for apparel exporters, allowing buyers to upload several invoices at once and helping users estimate their future cash flows. Suppliers chosen to join the platform may also receive early payments based on buyer’s credit ratings.

What has not yet been explored in Sri Lanka is using blockchain in preventing banking fraud. Blockchain allows for the strengthening of cybersecurity systems through its decentralised network. For example, in order for a hacker to corrupt data, he would need access to all computers on the network.

Corrupting data on a single computer will not be effective as the system analyses the entire mass of chains and excludes any data that does not match up. To facilitate the creation of such a system, banks could implement a system where customer transactions are verified through a digital fingerprint. The owner of the digital fingerprint can use it to submit new account applications and prove his or her identity universally, strengthening security systems for banks and providing a useful countermeasure against fraud.

The banking sector has made an effort to incorporate blockchain technology in a few different pockets of their operations. However, there are barriers preventing the adoption of blockchain technology to widespread banking activities. Suppose a customer wishing to make a payment through a bank wrongly inputs the value of the payment, since the transaction is replicated onto every node on the network, the bank cannot alter his entry as there is no central authority in the blockchain.

The solution to adopting blockchain to widespread banking activities lies in the construction of private blockchains which can only be accessed by a single bank, where identities of individuals are known and participants are preapproved. Individuals referred to as “Oracles” have special access to amend incorrect entries on the distributed ledger network, effectively solving the problem of data verification in a public blockchain. However, this would lead to an initial increase in costs for banks as participants would need to be preapproved for the private blockchain.

The creation of private blockchains can be used to combat the issue of data privacy in a blockchain system. Take the case where an organisation implements a public blockchain system without taking into account privacy concerns of data being stored in it, regardless of whether it interfered with data privacy laws or not – the data cannot be deleted without compromising the integrity of the blockchain. Currently, Sri Lanka has drafted a framework on data protection laws discussing the handling of consumer information. In the coming years, as data protection laws take shape in Sri Lanka, the utilisation of private blockchains by firms would allow for privacy concerns to be handled.

Benefits and challenges of implementing blockchain technology for voting

Another particularly useful application of blockchain technology is in voting. The election commission in Sri Lanka estimated the cost of the presidential election held this year to be Rs. 4 billion. Blockchain technology can end voter fraud and provide an efficient system to cut back on the massive expenditure for elections.

Costs can be cut in the form of physical security present, man-hours employed for the counting of votes, and boosting voter turnout. Individuals can vote online and this allows officials to count votes with absolute accuracy – knowing that each individual’s national identity card (NIC) can only be attributed to one vote. Fraudulent entries cannot be created using blockchain as once a vote is added to a ledger – it cannot be changed or erased.

A popular online voting system using blockchain technology is Polys. Estonia has its own online voting system built on blockchain and is seeing increased voter turnout, transparency, and large cost savings as a result of it.

That said, not everyone in Sri Lanka has access to an internet connection and a computer/mobile device. With smartphone and internet proliferation concentrated in the Western Province and digital literacy being roughly 25.5% overall, an online voting scheme built on blockchain technology may not be a feasible solution.

Programmes or workshops could be implemented outside the Western Province to educate individuals on how they could potentially vote online. A happy medium would be to establish a system where an individual is allowed to vote either at a polling station or online and integrate the two systems to prevent individuals from voting twice, similar to Estonia’s voting system.

Furthering blockchain implementation in Sri Lanka

Since Sri Lanka is currently gaining a foothold in the implementation of blockchain technology, the growth opportunities through the implementation of such technology to a vast majority of fields may not be clear or feasible as of yet. There are difficulties in taking this technology forward, as there is little to no endorsement by the Sri Lankan Government for blockchain technology.

With only a draft for data protection laws, the clashes it could have with public blockchains in the future are uncertain. Feasibility studies need to be carried out to truly assess how useful future projects implementing blockchain technology are for Sri Lanka.

For example, finding out what activities blockchain could serve from a public and private sector perspective, understanding whether ongoing projects can be scaled up. Afterwards, a policy could be devised to look into incompatibilities of proposed blockchain-based solutions and existing legal and regulatory frameworks.

It is important for such a policy to not lean too far on either side of the spectrum – being too restrictive or on the other end, being too permissive to effectively leverage blockchain for growth in Sri Lanka.

[Malitha Goonaratne was a Project Intern at the Institute of Policy Studies of Sri Lanka (IPS). To view this article online and to share your comments, visit the IPS Blog ‘Talking Economics’ – http://www.ips.lk/talkingeconomics/]