Monday Feb 16, 2026

Monday Feb 16, 2026

Thursday, 3 March 2022 00:30 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By The National Movement for Social Justice

We are in the throes of an unprecedented crisis. No useful comparisons may be drawn from the 2001-02 period of negative economic growth. The only analogue may be from 90 years ago, when per capita GDP collapsed from $ 80 to 33 in a few years as part of the Sri Lankan manifestation of the Great Depression. Conventional politics based on the auction of non-existent resources offer no solutions to this crisis. Problems that have festered for over seven decades must be honestly analysed and root causes addressed courageously and collectively.

The purpose of this discussion document is not the presentation of complete or perfect solutions to all problems that beset our society and economy. It has the limited objective of clearing a path out of the crisis in a manner that prevents periodic recurrences, as has been the case in the past. We believe that this document, which was prepared by drawing on the expertise of many, has room for further improvement. To enable agreement to be reached within a reasonable timeframe, we present five preconditions for the implementation of the economic measures, seven immediate actions, and four actions that must be initiated now even though their fruition is unlikely within the proposed two-year timeframe.

Unbearable burden on the people

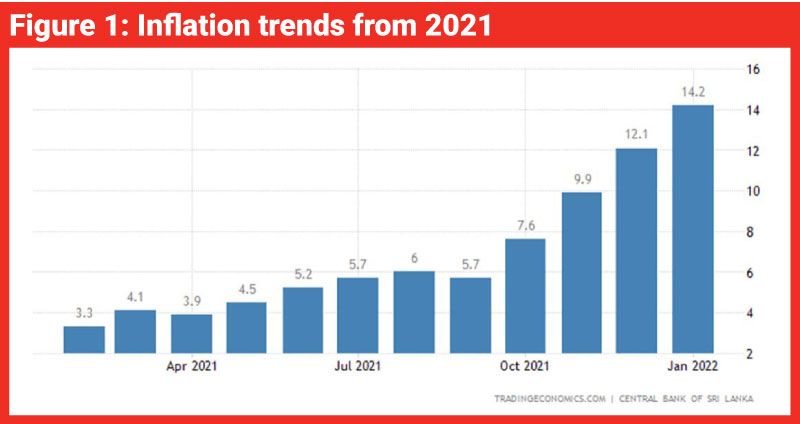

Our people are beset not only by shortages of essential items, but also by escalating prices. In January 2022, the annual inflation rate increased from 12.1% to 14.2%. The inflation rate for food which was 22.1% in December 2021 increased to 25% in January.

It has become a struggle to prepare the food one has obtained at a high price. Cooking gas is in short supply; its price has doubled. Alternatives have also been affected. All businesses, including micro enterprises, that depend on a reliable supply of electricity are in difficulty.

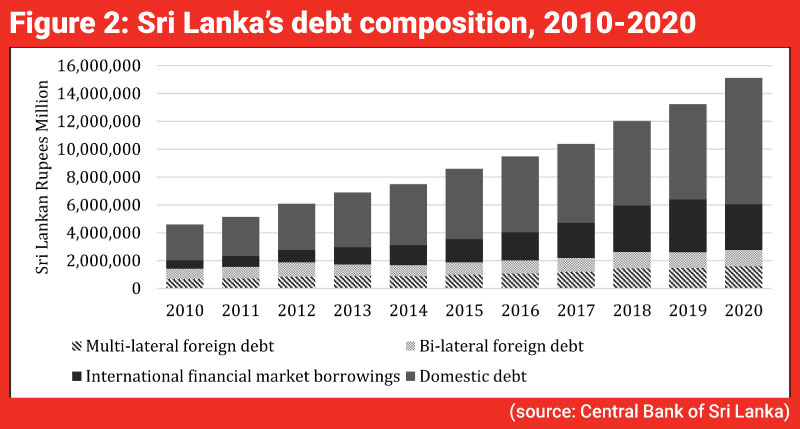

The immediate causes of the present difficulties of debt management are the commercial loans obtained since 2007 for non-revenue yielding projects. The problem was aggravated by the ill-considered tax breaks given in 2019. Underlying all this was a fundamentally unsound economy afflicted by twin deficits (fiscal and current account) that were not addressed by any government since Independence. The self-inflicted reduction of state revenues over the past two years resulted in the inability to manage the accumulated debt burden.

What the people see is a flailing government that is exacerbating problems through ill-considered actions. Examples are plenty. The Government banned the import of fertiliser, weedicides and insecticides overnight in the name of making Sri Lanka the world’s first country with 100% organic agriculture, though the desire to conserve foreign exchange and get rid of the subsidy burden may have played a part. The end results include increased costs of food imports, massive compensation having to be paid to farmers, and $ 6.7 million being paid for unusable fertiliser imports. The Government’s efforts to maintain an artificial exchange rate has resulted in the drying up of remittances from workers abroad.

We are no longer talking about a crisis that is to come; we are in its midst though not in its depths. The 2022 Budget offered no remedies for the twin deficits and has led to the worsening of shortages and black markets. Most of the new revenue proposals are one-off. Where will the revenues come from in 2023? Most of the cost cutting is cosmetic. The additional expenditures proposed in January 2022, unaccompanied by new revenue proposals, add to the confusion. Those in the informal sector who suffered the most have not been offered any relief.

This is not about one bad year; it will drag on. Simple arithmetic will show that it is not possible to pay our debts which average around $ 5 billion per year and maintain the levels of imports necessary for the normal functioning of the economy. The improvisational responses result not only in the worsening of the living conditions of the people; they are causing long-term harm to export industries as well as to those supplying the domestic market. Not only is new investment being discouraged, but existing firms are being incentivised to relocate. Small, medium and micro enterprises are being decimated. The effects of the present economic mismanagement are likely to be felt for decades.

The necessity of debt restructuring

The 3.6% contraction of the economy in 2020 is merely a sign of things to come. Sri Lanka has the highest income inequality in South Asia (between China and the US in international comparisons) and provided the least compensation for the harms caused by the pandemic and lockdowns. Our citizens in the lower deciles are unable to withstand more shocks.

We will not be able to get out of this crisis without any pain. But we can minimise the pain, especially for the most vulnerable, by a well thought out recovery program that includes a debt restructuring program involving the IMF. The likelihood of achieving monetary stabilisation is higher if the IMF is involved.

We should not abandon the commitments to fiscal discipline on the first possible occasion, as was the case in the past. We must stick with these reforms because they are our decisions and because this is the only way recurrences can be avoided.

The Government may be unwilling to accept working within the framework of an IMF program because of the fear of being made responsible for the difficult, but necessary, reforms.

That is why we should collectively get behind a common minimum program which provides a meaningful role to the opposition parties and is anchored on Parliament’s Constitutional responsibility for the control of finances. This is also likely to put a brake on the perpetual blame game. Unless these actions are taken, Sri Lanka may well end up like Lebanon.

Essential pre-conditions

The 20th Amendment must be rolled back. It is essential that the minimum program be implemented over a minimum of two years if we are to get on the path to recovery. The present Constitution, especially after the enactment of the 20th Amendment, makes the President extraordinarily powerful; it is not conducive to meaningful collaboration among parties represented in Parliament. It was seen in 2018 that the 19th Amendment was the best defence against overreaching Presidential power. Therefore, restoring the 19th Amendment with some pragmatic accommodations is a foundational pre-condition for a cooperative effort to bring the country out of crisis.

Proper appointments must be made to the independent Commissions. The appointments made to the Commissions at the whim of a single individual must be reversed and fresh appointments made through the Constitutional Council. A central bank that is independent and acts professionally requires a Governor appointed through the proper procedures.

The Provincial Councils must be activated. The much-delayed Provincial Council elections must be held forthwith, based on the old law. This will allow the Provincial Councils to fulfil their responsibilities, and permit the central government to focus on economic recovery.

The common minimum program must be implemented over a minimum of two years. The 20th Amendment makes it possible for the President to unilaterally dissolve Parliament any time after February 2023; under the 19th Amendment that would have been possible only after February 2025. It is necessary to focus on economic recovery for a minimum of two years without the diversion of election campaigning. At least that length of time is needed to lay the foundation for tackling the twin deficits through structural reforms and the restructuring of debt.

Democratise the media space by regulating frequency-using and related entities through an independent commission. It is necessary to introduce a formal, independent regulatory system through legislation for all entities using electromagnetic frequencies and related media enterprises. The objective is to democratise the media space. It will be difficult to build the public trust necessary for the successful implementation of the recovery program in the current media environment. This will also enable the realisation of the currently unrealised value of spectrum and increase the transparency of the allocation process. Transparent auctions of frequencies can yield significant revenues for the state. The benefits of this action, that are best done in a non-partisan manner, are both political and economic.

Elements of a common minimum program

A common minimum program must be discussed and agreed upon by interest groups including but not limited to political parties represented in Parliament. The list below is not final and is intended to initiate the discussion. Below are suggested immediate and medium-term actions that will address the twin deficits and build trust in the recovery program.

Immediate actions

1. Relieving ourselves of the burden of at least one white elephant. A headline grabbing action that will effectively communicate the seriousness of the common program in achieving economic recovery is essential. Selling off SriLankan Airlines as was done with Air India appears a good candidate. Calculated based on 2018, 2019 and 2020, the average loss per day incurred by SriLankan is Rs. 99 million. The Treasury will be protected from further losses on this scale by a sale. Similar to the Indian government which sold off 100% of Air India and retained responsibility for some of the accumulated losses, the Sri Lanka Government may also have to take on at least a portion of the accumulated losses, while giving complete control to the buyer. This action will serve to reinforce the statement in the 2022 Budget Speech that losses of state-owned enterprises (SOEs) will no longer be covered by the Treasury. The sale will protect the Treasury (and taxpayers) from never ending demands for handouts. Debtors will receive a clear message that we are serious about getting our house in order. The proposal to sell SriLankan Airlines should not be interpreted as a blanket call for privatisation. The reform appropriate for each SOE will take different forms. For example, simply selling land owned by the Railway Department will not result in the improvement of passenger or freight services. While it is important to end the haemorrhaging of public funds, weight must also be given to how services to the public can be improved through sector-wide reforms, not limited to the SOE only. As was done in telecommunications, competition must be introduced where feasible under formal regulation and actions must be taken to change the internal culture of the SOE being privatised. This may require the setting up of PPPs similar to Sri Lanka Telecom.

2. Introduction of formula-based pricing for petroleum products and related services. Formula-based pricing should be introduced for imported petroleum products, including cooking gas. This is essential for addressing the twin deficits problem. Refined and crude oil imports amount to around 15% of Sri Lanka’s total merchandise import bill. These prices are determined by international market forces. Unless the increases driven by these market forces and the devaluation of the rupee are passed on to the end consumers, the difference must be covered by public funds, thereby widening the fiscal deficit. Application of formula-based pricing will ripple through the economy, including electricity and water supply. These services should be brought under formal public utility regulation and tariffs that reflect costs should be set. The poor who are disproportionately affected by the price movements should be provided with targeted subsidies as described below.

3. Accelerating the establishment of an efficient and flexible social safety net. The ongoing initiative to consolidate over 40 welfare schemes under the Welfare Benefits Board and build a beneficiary database must be quickly completed. Because the pressure on the rupee is likely to continue for some time leading to increases in prices of essential items, it will be necessary to develop the targeted subsidy scheme using the resources available under the World Bank funded social safety net project. Implementing the social safety net will alleviate the pain that comes with the reforms. If it is possible to close down the Samurdhi Department whose personnel eat up 25% of the total allocations for Samurdhi as part of this consolidation, it will send a powerful message about the seriousness of the effort to tackle the fiscal deficit.

4. Establishing an independent Central Bank. Many observers have concluded that the actions of the Central Bank have contributed to the aggravation of the present crisis. Unless a specialist committee is forthwith tasked to come up with re commendations on reforms, including reactivation of the Monetary Law Bill that is currently not in consideration, and are acted upon quickly, it is likely that problems will recur.

5. Increasing State revenue. A long-term solution to chronic fiscal deficits must include increases in State revenues. In the name of fairness, indirect taxes (now contributing around 80% of the total) must be decreased to around 60% within a few years with the difference being made up with a greater contribution from direct taxes. It is true that the 2019 tax breaks reversed the progress that was being achieved in this regard. However, it may not be feasible to restore the status quo ante at once, given the economy is in crisis and many taxpayers are in distress. The tax reforms should be implemented carefully and gradually, beginning with perhaps the increase of the VAT rate, restoration of PAYE and broadening the income tax base. Retrospective taxes, super or otherwise, are not advisable.

6. Export promotion. Promotion of exports is a high priority. There is no need to start from scratch as some politicians believe, because a broadly consulted National Export Strategy (NES) exists. Based on data and systematic analysis, six priority sectors, including electronics and software and BPM, have been identified. The sectoral committees responsible for implementation have been operating for some time. As Prabash Subasinghe, the Chairman of the Export Development Board appointed by the President in 2019, correctly stated there is no need to work up new priorities and strategies; the NES implementation should continue. Each of the NES Committees should meet regularly with teams of relevant officials to identify the difficulties experienced by exporters including the re-emerging license raj and the ever-changing bank regulations. The recommendations of these committees should be acted upon speedily by a high-power government committee.

7. Assuring market access. Market access is of great importance in these post-pandemic times because all economies are under stress and protectionist sentiments are rising. The first steps would be the completion of the bilateral trade agreements with India and China that have been under negotiation for some time. They must be given priority because of their current and future economic significance. The next priority should be creating the conditions to join the RCEP which came into effect in January 2022, and which is already providing advantages to competitors such as Viet Nam. If policy stability and market access can be assured through trade agreements, it will be easier to attract foreign direct investments.

Medium-term actions

1. Reducing energy imports. Refined and unrefined petroleum products are responsible for around 15% of the total merchandise import bill. Irrespective of one’s stance on economic policy, it is difficult to argue that a reduction of import expenditures will not help narrow the current account deficit. But the reduction of the import of investment and intermediate goods (making up 80% of the total) is difficult except in the case of petroleum products. The reduction of these imports will also be welcomed by environmentalists. These imports are mostly consumed by the over seven million two, three and four wheeled vehicles now operational in the country. Depending on rainfall patterns, imported petroleum is also used to produce electricity. Greater reliance on hydro, wind, and solar, which are plentiful within the country, and gradual conversion of the powering of transport to electricity, will allow reductions of fossil fuel imports. However, it is not possible to significantly increase the use of intermittent sources such as wind and solar without making major investments to modernise the transmission grid and connect it to the Southern Indian grid. The intermittency and volatility of these sources requires their contribution to be kept in the range of 15-25% of the total supply. If the small Sri Lankan grid is interconnected to a larger grid through an HVDC cable, the amount of energy from intermittent sources that can be absorbed is much higher. Sri Lanka has an evening peak in electricity use, different from India’s. This will help to reduce the high costs incurred in supplying the peaks in both systems and in avoiding load shedding. Due to the need to conduct the necessary studies and mobilise the resources for the modernisation of the grid, it will not be possible to see results within the two-year timeframe. However, if we are to reduce the current account deficit and respond effectively to climate change, action must be initiated now.

2. Upgrading state service personnel. To reduce the fiscal deficit and to provide better services to the public, it is necessary to improve and upgrade the administrative service and other state services. The efficiency of the state machinery must be enhanced. A pre-condition for this is the immediate cessation of further unsystematic recruitment. The actual personnel requirements of the State, of the armed forces, and SOEs must be calculated, and surplus personnel redeployed. The State must make major investments to upgrade the capacity of the retained personnel. To assure productive performance, they must be provided with the necessary facilities. This should not be limited to tangible things such as computers, but must include proper performance reviews, the formulation of customised training plans and the provision of necessary resources for training, etc. Professor Mick Moore, a long-time observer of the Sri Lankan state has documented the decline of the resources spent on making state employees more productive at the same time as the numbers of employees have been going up. This must change.

3. Review of National Export Strategy. The NES for 2018-2022 was developed based on systematic methods of identifying the products and services with the greatest export potential and broad consultation with knowledgeable exporters. Outside that strategy, it appears that some observers are placing a great deal of weight on the potential of mineral sands, graphite (a major export in the 1930s), etc. Therefore, it would be appropriate to review and update the NES, paying attention to pandemic-related changes and specifically to the potential of the above natural resources (including the technical skills and capital that are needed and the value chains that the local industry must become part of).

4. Formulation of a stable tax policy. A stable, long-term tax policy must be formulated through broad consultation, ending the practice of tailor-made provisions to favour one group or another. The now obsolete policy of attracting foreign investment using tax concessions must be replaced by one that is consistent with the OECD led agreement to impose a 15% minimum tax on global companies, which has already attracted 136 signatories.