Tuesday Feb 17, 2026

Tuesday Feb 17, 2026

Monday, 11 March 2019 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Avocado Collective

On reading Victor Ivan’s ‘What went wrong with Sri Lanka?’ (22 February), one is struck by how often Sri Lankan commentators repeat memes from conventional historical wisdom without actually checking on their accuracy.

In his quest to prove the benevolence of the British Raj and its supposed positive impact on the people of Sri Lanka, Ivan makes the spurious claim that in the Kandyan Kingdom, “The rate of infant mortality at birth and the rate of infanticide or intentional killing of infants for various reasons like economic hardships and credulous (astrological) beliefs remained high. The literacy rate too stood at a very low level.”

Life in the Kandyan Kingdom must surely have been hard for the average peasant but we wonder whether Ivan has the superhuman ability to conjure up statistics that were simply never recorded in the 18th century!

Ivan invokes Robert Knox, who was a prisoner after all with limited knowledge of the entire country, to show how poor the peasantry were in the Kandyan Kingdom. However, Ivan makes no effort to compare the position of the Sri Lankan peasantry with the peasantry of contemporary Britain or even India. Furthermore, Ivan also fails to substantially demonstrate whether colonial rule actually improved the lot of the Sri Lankan peasantry.

What the English built (or what they destroyed)

Ivan makes much about the “significant progress” that English colonialism brought to the country. In his expert opinion:

“The feudal system of production, the productive forces of that system which constituted the main elements of it and the relations in production process, production techniques and feudal institutions associated with it, were to a great extent wiped out or weakened by the British. In fact, these elements cannot be considered as entities which ought to have been preserved. Instead they deserved to be destroyed for the progress of the country and the benefit of the people.”

We are no defenders of feudalism and feudal modes of production. Yet, what did the English in fact destroy? And to what extent did they replace feudalism with a modern industrial capitalism?

In the first place, the English Raj’s murderous sprees in 1818 and 1848 destroyed much of the peasantry’s able-bodied labour force, their productive agricultural fields and their buffaloes. Needless to say, these actions crushed agricultural productivity. The peasantry was pushed backwards from the use of working animals to pure manual labour. Combined with the wilful destruction of the ancient irrigation system, any hope of capital accumulation in agriculture was foreclosed upon.

Secondly, in order to raise labour for their plantations, they did away with the ‘Rajakariya’ work levy system in 1832, on which the maintenance of public works such as the roads and the irrigation system, depended, without replacing it with a sustainable alternative.

Thirdly, the English dispossessed the entire peasantry and imposed Sri Lanka’s version of “enclosure” with three successive acts: the Crown Lands (Encroachment) Ordinance of 1840, the Registration of Temple Lands Ordinance of 1856, and the Waste Lands Ordinance of 1897.

These acts took away the peasants’ right to use common and forest land (as well as some of the paddy land). Traditionally, the peasantry relied on the forest land not only as a rainwater catchment and for timber, but for herbs and for chena (swidden) cultivation. Whereas paddy cultivation was mainly for subsistence, with just a little surplus for the market, chena and home garden cultivation was essentially for the market. By depriving the peasantry of their common and forest land, they essentially destroyed the modern, market part of the agrarian economy.

As a result of all this, the formerly rice-exporting Kandyan provinces became part of the rice-importing and wheat-importing colonial set-up. The English, far from destroying the feudal system, imposed their own version of it on the peasantry. Far from playing a “progressive” role, as asserted by Ivan, they played a reactionary one.

What did the colonial government do to the forest lands they expropriated from the peasantry? They first of all cut down all the trees and killed all the elephants who lived in the forests of the upcountry. They replaced the trees with a coffee monoculture, which leached the soil of nutrients and robbed it of all its moisture. This affected the peasantry downstream, who found themselves without water for irrigating their crops, and went looking for lands uphill. Then the English evicted them under the Wastelands Ordinance.

The Planter Raj

After expropriating the land, the English “sophisticated civil service composed mainly of career bureaucrats and a reputed Judiciary” sold the land to themselves at five shillings an acre! Among the people who bought land on a single day were the Governor, the Army Commander, the Chief Justice, the head of the Road Department, and so on. Although later the civil service lost the privilege of selling to themselves the land they expropriated from the peasants, this established the interlinkage of the plantations and the state machine, and the identity of interests led to the nexus being termed the ‘Planter Raj’.

Among the detrimental things the Planter Raj achieved was the development of Colombo as the main port, rather than the more logical, flourishing port of Galle – which lay closer to the sea lanes. The development of Colombo cost more than twice what the development of Galle would have, and the government carried it out in order to enhance the planters’ profits.

The Planter Raj continued long after 1948, indeed until the land reform and the nationalisation of plantations in the 1970s. Sri Lanka was ruled, essentially, by a stratum of rentiers, with interests in plantations, trading and moneylending. The dominance of this class, which continues today, constantly undermines the industrialisation of the country.

Sri Lanka in 1948

Coming closer to modern times, Ivan regurgitates the oft-repeated but utterly false truism that, in 1948, Sri Lanka, “was second only to Japan in terms of per capita income. But, the gap between the two countries was not so big. Per capita income gap was very narrow.”

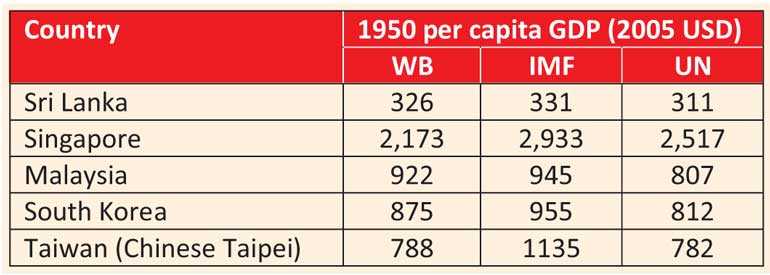

The fact of the matter is that nobody has calculated, with any degree of accuracy, Sri Lanka’s per capita income in 1948. One authority (the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation) has imputed, from later data, the 1950 gross domestic product (GDP) per capita of various countries according to the World Bank (WB), International Monetary Fund (IMF) and United Nations (UN).

The figures given in the table indicate that quite clearly that at least four other Asian economies besides Japan out-performed Sri Lanka by considerable margins in 1950. It is unlikely that the situation could have been significantly different two years before.

It should be noted that GDP is not necessarily a good measure of the wealth or development of a country. GDP merely measures the total value-added in transactions, and does not take into account a country’s capital assets. Thus, when measuring the wealth of Singapore or South Korea, GDP does not include the huge amount of capital assets (especially in terms of marine engineering and logistics) of the former, or the extensive capital works carried out on the agricultural land of the latter.

By way of contrast, Sri Lanka had almost nothing in terms of productive capital assets. We had a dominating plantation sector which relied heavily on “cheapened” human labour, in debt-peonage at almost the level of slavery, and a subsistence peasant sector, again in debt-peonage. Industry, apart from graphite mined in inhuman conditions, was virtually non-existent outside the tea and rubber factories, which used imported machinery, with hardly any substitution of capital for labour. The reduction of labour intensity in the plantations was marginal.

Ivan goes on to state that, “Sri Lanka was considered the country which had the best road network in Asia. It also had the best railway service in Asia. The Colombo harbour was acknowledged to be the best harbour in Asia.” Who said so? He could at least cite one source.

Take Colombo harbour, for example. As of 1948, nothing significant has been done following the construction of petroleum facilities in 1922. On the other hand, Singapore was under continuous development in that period. The English constructed their biggest naval base in Singapore, with a huge tank farm with 500 oil tanks – the Trinco tank farm never had more than a fifth of that number. The harbour also had extensive marine engineering and docking facilities.

Shoddy economic indicators and selective comparisons aside, the truth is, as political economist S.B.D. de Silva noted: “We inherited from English colonialism the most impoverished peasantry in Asia.”