Tuesday Feb 24, 2026

Tuesday Feb 24, 2026

Friday, 5 June 2020 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

|

Artifical Canal cut through the beach

|

The Pearl Protectors and the Centre for Environmental Justice are highly concerned about the lack of consideration for socio-environmental impacts of the Mount Lavinia beach nourishment project in the absence of an Environmental Impact Assessment, and the wastage of public funds by the Coast Conservation and Coastal Resource Management Department (CCD) in conducting the beach nourishment project.

The Pearl Protectors is a volunteer-based organisation that advocates for the conservation and protection of Sri Lanka’s marine environment, and the Centre of Environmental Justice is a non-governmental organisation which aims to protect the environment and ensure equal environmental rights for all people.

The project, worth Rs. 890 million, commenced during curfew amidst environmental concerns raised by residents who had not been previously informed. The Calido beach in Kalutara and Ratmalana / Angulana beaches were also included in the said project.

Contradicting statements

As the said project is located within the coastal zone, its approval falls under the ambit of the CCD. Hence, the Coast Conservation and Coastal Resources Management Act no. 57 of 1981 stipulates a permit from the Director General of CCD for any development activity (any activity likely to alter the physical nature of the coastal zone in any way…) proposed within the coastal zone. Further, section 16 of the Act states that the DG may request an Initial Environment Examination (IEE) or an Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) upon application for such permits. Moreover, an EIA report is required to be open for public comments for a period of 30 days. The project proponent should then respond to such comments received.

On 19 April, the Director General of CCD claimed that an EIA report has been obtained for the project, that was still ongoing at the time, and dismissed any concerns that may arise on the impact to the environment. However, he later told the media on 28 April that neither an IEE nor an EIA had been conducted for the sand filling in Mount Lavinia.

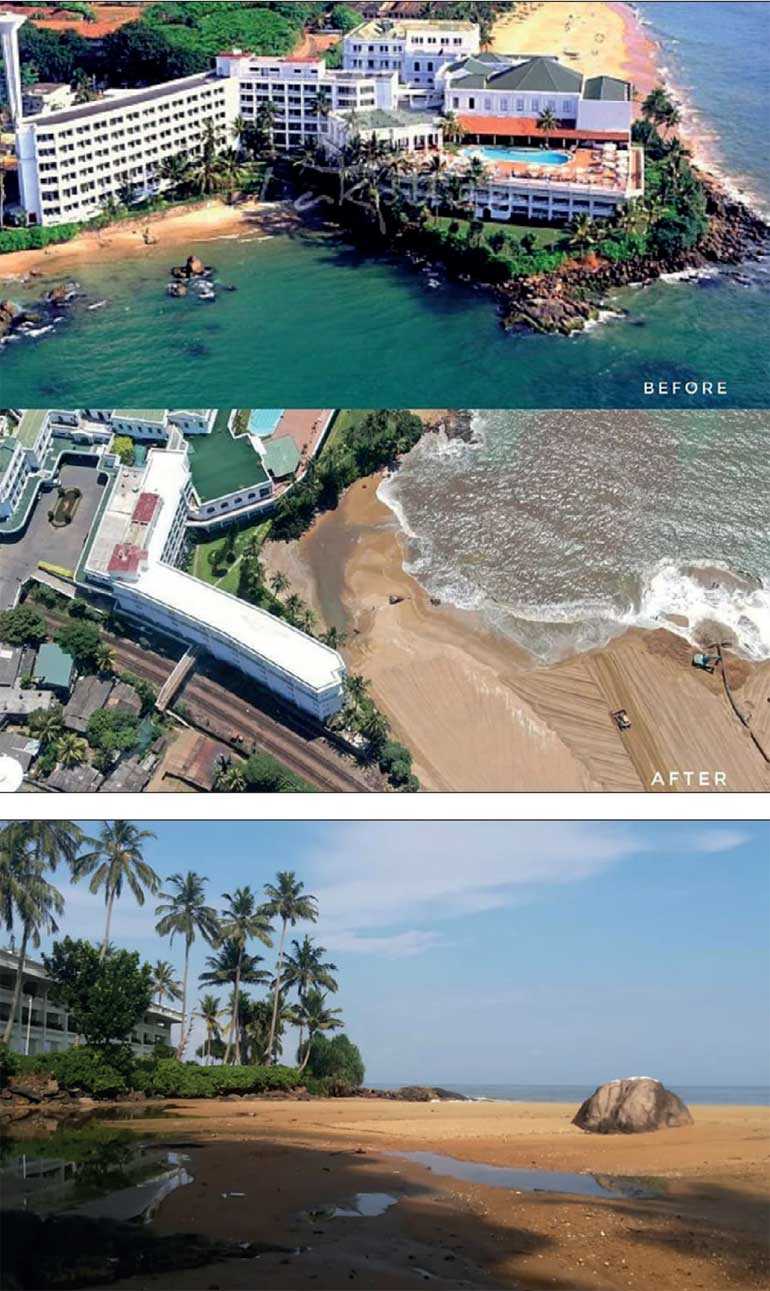

Recently, the project sparked the attention of the public after photos circulated on social media (30 May) revealing further erosion of the ‘nourished beach’ in a matter of 40 days after completion. The Director General of CCD swiftly addressed the concerns in several interviews, stating that the washing away of the sand is a beach nourishment strategy called the ‘sand engine’ method, which he failed to mention before when the public first raised concerns on the possibility of this happening back in April. Noteworthily, as reported by the media on 3 May, the nourished Calido beach also had a similar fate where the sand was washed away by the waves but the Director General is yet to address whether that too was part and parcel of the beach nourishment completed in Calido. To our knowledge, the sand engine method has many physical and natural parameters to consider, including a transparent process as practised in the Netherlands and some other European countries.

No EIA, or even an IEE

According to several interviews given by the Director General of CCD, his view is that an EIA is not necessary for projects where there is a high risk of erosion. This statement is problematic due to three main reasons.

Firstly, the CCD is both the project proponent and the Project Approving Agency of the said project. Hence, in approving the project, the CCD is in violation of the natural justice principle where one cannot be the judge of his own case.

Secondly, when speaking to the media on 17 September, the Director General did not recognise Mount Lavinia Beach as a “danger zone” for coastal erosion. The severity of the erosion spoken of is also debatable since century-old photos of the iconic Mount Lavinia beach are no different to what appeared prior to the nourishment.

Thirdly, while the Act may provide discretionary power to the Director General to decide on whether an IEE or EIA should be conducted, it must be done with a proper assessment of the facts as upheld by the Court in the case filed against the CCD for the Karagan Lewaya (No. 555/87). In addition, according to his Lordship, Justice Amerasinghe, in the Bulankulama v Ministry of Industrial Development case (2000 3 SLR 243), “The EIA process should also help public officials make decisions that are based on understanding environmental consequences and take actions that protect, restore and enhance the environment.”

Further, Article 27(4) of the Constitution embodies the directive principles of State policy where the State is to protect, preserve and improve the environment and Article 28 refers to the fundamental duty upon every person in Sri Lanka to protect nature and conserve its riches. The CCD is no exception to this constitutional duty.

In addition, the DG has claimed that with regards to sand burrowing, he has obtained an EIA. However, the CCD has burrowed sand outside the coastal zone (only 2 km from the low-tide level comes under the CCD jurisdiction) which is about 5 km from the beach and that comes under the purview of the National Environmental Act. The said sand burrowing has been done based on an EIA conducted back in 2012 for the Unawatuna beach nourishment. It is wrong to make a decision based on such an old EIA, since the seabed may have been undergone changes due to various actions over the last 8 years.

In this backdrop, the decision to avoid an EIA that would factor in the broader socio-environmental impacts by consulting all stakeholders and calling for public comments for a project that facilitates public funds is inadmissible. The absence of an EIA report will continue to leave a list of unanswered questions about the status of the environment before the nourishment, project justifications and alternatives, as well as further claims made by the Director General about how the nourishment would boost tourism and benefit the fishing industry. The Pearl Protectors and Centre for Environmental Justice strongly believe that the Act must be interpreted in favour of the environment and the general public, hence for EIAs to be made mandatory for projects of this nature.