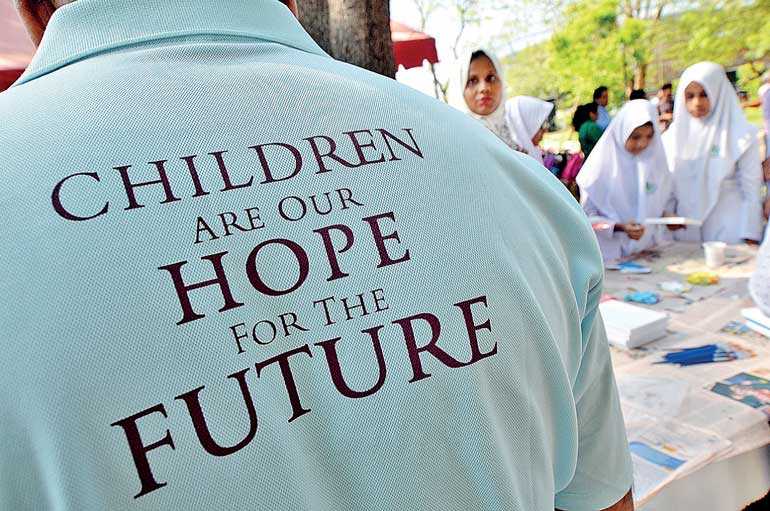

Progressive decline of the quality and standards of education provided at all levels in the State sector is further hastened by the ad hoc and hurriedly designed responses to meeting the increasing demands for education – Pic by Shehan Gunasekara

- For the attention of Presidential Election 2019 candidates:

By Ratnasiri Arangala, A. M. Navaratna Bandara, Michael Fernando, Wipula Karunathilake, Mohammed Mahees, Sasanka Perera, and Jayadeva Uyangoda

Sri Lanka’s entire system of education, at pre-school, primary, secondary, and tertiary levels, has been facing multiple crises. Attempts made in the recent past to address some aspects of these crises have either succeeded only partially or failed altogether.

The persistence of these multiple crises has also generated new interest in educational reforms among Sri Lanka’s presidential candidates in the 2019 presidential campaign.

It is reported that the main presidential candidates have assigned the responsibility to design policies on education to their own groups of advisors. Their proposals are probably included in their election manifestoes and campaign promises.

Renewal of such interest in resolving the ever-sharpening crisis of education would be meaningful only if new ideas lead to transformative policy reforms.

We are a group of professionals deeply committed to reforming and strengthening Sri Lanka’s education at all levels. In this context, our intention is to present a few approaches that we believe will lead our country’s system of education out of these multiple crises.

We offer the following brief analysis and agenda for reform to the attention of all presidential candidates, their committees of advisors, political parties they represent and, last but not the least, citizens and voters of the country for reflection and action.

Current crisis

Sri Lanka’s current state of crisis in education has been ably explained by researchers and policy experts in a variety of ways, drawing attention to its many dimensions. We wish to highlight the following anomalies that have made the overall crisis of education intractable. Their resolution indeed calls for major policy interventions spread over short-term, medium-term, and long-term basis:

- The ever-increasing social demand for school, tertiary, and higher education continues to remain only partially met. This is a condition caused by the severe incapacity of the existing State-run educational system for further expansion, modernisation, quality improvement, and fulfilling social aspirations.

- Progressive decline of the quality and standards of education provided at all levels in the State sector is further hastened by the ad hoc and hurriedly designed responses to meeting the increasing demands for education. The growing mismatch between expansion and quality is observable in school, vocational, and university education.

- Early childhood education continues to remain an informal and ad hoc branch of education with no policy towards accreditation of service providers. It lacks an active and robust involvement of the Education Ministry in monitoring quality, standards, type of education, facilities available, prevailing hygienic conditions, child protection, services in place, and professionalism of teachers. As a result, this sector has become a huge, yet unorganised sector of education. In instances where quality education is provided, the fees are high and unaffordable to most parents.

- Poor nutritional conditions among school children, particularly due to increasing economic hardships experienced by the low income and lower middle class families, are a forgotten policy issue. The prevalence of poor nutrition extends even to students in universities and tertiary educational institutions where the majority come from low income social backgrounds.

- Improvements in school education are severely hampered by the state of stagnation in professionalism among most schoolteachers in their teaching, training, evaluation, and mentoring skills. Most teachers practice only one, and of course wrong, teaching method. It involves (a) dictating notes to students, (b) forcing students to memorise model answers and repeat them at public examinations, and (c) persuading students to prepare only for the so-called target questions.

- Schoolteachers in general are also handicapped by not having opportunities to update their subject knowledge, or acquire new skills. As a consequence, they fail to inspire students for creativity.

- The involvement of private sector to provide parallel education opportunities has led to many distortions and negative outcomes about the goals and benefits of education. Rising cost of education caused by the entry of an un-governed tuition industry has severely undermined the very idea of free education. It has also created a state of anarchy in school education.

- The unchecked proliferation of profit-seeking private educational institutions, without any regulatory framework in place, has led to new disparities in the access to and benefits from the private sector-led education. At present, there are no government mechanisms to ensure quality and standards of education and training provided as well as assessments and examinations conducted by these institutions. Thus, they have the potential to undermine the social mission of education as a civilisational resource.

- The incapacity of the industry in both the State and non-State sectors as well as the economy to generate adequate employment opportunities for the educated youth at all levels continues unchecked. The proliferation of private higher educational institutions caters primarily to very limited segments of society. This situation is likely to sharpen the social disparities in the access to employment both in State and private sectors.

- The entire sector of higher education stagnates in a grossly outdated model of university undergraduate institutions inaugurated as far back as the early 1940s. It sought to produce recruits for the public sector as well as medical and technical professions. No effort so far has been made by any government to change and modernise this relic from the colonial past.

- There have been many ad hoc and costly responses to periodic pressures from global economic and labour market trends. Such reform measures implemented in school and university education have systematically ignored locally generated visions and perspectives for sustainable rebuilding of the country’s education. The neglect of constructive inputs from local intelligentsia and their resultant apathy for change in the educational sector has led to the lack of participation by the direct stakeholder communities.

- Sri Lanka has not yet succeeded in developing and supporting its Tertiary and Vocational Educational Training (TVET) sector into a robust and forward-looking branch of education. It is expected to serve the employment aspirations of young school leavers around the age of 16. However, it fails to attract them in adequate numbers. Among the reasons are (a) unattractiveness of courses and training it offers to the new generation of youth, (b) absence of a system of adequate financial support for students, (c) failure to cater to the needs and vocational aspirations of women students, and, (d) conservative nature of the overall educational outlook that is not yet ready to respond to the challenges and opportunities of the Fourth Industrial Revolution.

- Policy-thinking for transformative reforms in the education sector is also blocked by the narrowly politicised reactions by a range of vested interests. Prominent among them are various post-Independence governments, political parties, teacher unions, and student unions. Similarly, the continuous failure by the academic communities and their professional associations to offer research-based alternative policy options has made public discourse on educational reforms poorer.

- Gender composition of student populations in school, university, and vocational sectors is changing rapidly due to the higher participation of women than men in almost all levels of education and in most fields. This is a major facet of democratisation of education in Sri Lanka. However, educational institutions as well as the labour markets have not yet made meaningful adjustments to accommodate this demographic change. Facilities available at educational institutions are still insensitive to the needs of the majority of students who are women.

- Vocational training is still conventional in orientation that re-affirms gender stereotyping. There are no incentives for women students to join the vocational fields that have traditionally been reserved for men. The field of employment continues to discriminate educated and professionally qualified women in recruitment as well as promotion.

- The present state of dispersal of institutional responsibilities for educational reforms among key Government institutions is a major handicap for policy innovation. This fact also remains unacknowledged. Policy-making and implementation in education is spread across a vast institutional scheme. It covers the President’s Office, Prime Minister’s Office, the Cabinet, Education Ministry, Higher Education Ministry, Provincial Councils, University Grants Commission (UGC), National Education Commission, and National Institute of Education.

This state of diffusion of responsibilities calls for an institutional focal point for coordinating the process of policy-making and guiding policy implementation.

A long-term vision

We stress that a policy vision with commitment to effective implementation is needed to take Sri Lanka’s education out of the present crisis and re-orient its future developmental path. Such a vision requires a democratic political leadership that can establish a broad coalition of stakeholder communities along with a commitment to championing a process of nation-building though modernising Sri Lanka’s education at all levels.

Such a modernising vision should contain the following normative principles and strategic considerations:

- Education is a fundamental right of all. It is the duty and obligation of the State to ensure that all citizens have access not just to education, but to quality education without discrimination or deprivation on any basis.

- Education is a vital means for social transformation, social equality, social mobility, democratic citizenship, pluralistic nation-building, and realisation of individual and community aspirations. Thus, preserving and promoting the capacity and role of education as the driving force for positive social change as well as individual and social upliftment should be integral to the social contact between the government and citizens. This calls for a clear commitment on the part of policy-makers that equity matters at all levels of education.

- However, such responses should be carefully formulated by taking into account local conditions. Further, these responses need to be transformed into policy and implemented without causing new waves of social exclusion, group marginalisation, political upheavals, or national crises. That calls for building broad social and stakeholder coalitions through dialogue for major policy reforms in education.

- Any new reform should also reflect the reality that Sri Lanka is a multi-ethnic, multi-cultural, and multi-lingual society. Educational reforms at all levels should be guided by a vision for building citizens for a democratic society with pluralistic values.

- Sri Lanka’s education needs to respond to new demands from global economic change, industrial and technological revolutions, and restructuring of labour markets. A new emphasis on vocational and professional educational needs to be carefully calibrated with school and university education. For its success, active collaboration between different agencies representing the State and non-State sectors as well as the external donor community will be needed.

A framework for short and medium term action

We propose the following actions for policy intervention which also reflect the current thinking among many reform constituencies in our society. They point to policy innovation and building new institutions while re-building and reforming the existing ones. These are measures that require clarity of objectives with a vision for preventing bureaucratisation. Sustainability of reforms as proposed below also calls for building broad stakeholder coalitions. Continuous dialogue with stakeholders should be built into the strategy of managing change in all areas of the educational sector.

Early childhood education

Policy challenge: Early childhood education (ECE) is a vast and still expanding sector in Sri Lanka’s education. It is presently run and managed by individual initiatives with small-scale private investment. The absence of State investment, lack of a clear legal framework to govern the provision of ECE and the implementation of existing ECE policies, weak mechanisms for monitoring and enforcing compliance, and the absence of quality assurance in all its aspects are crucial issues that require solutions.

Reform proposals

- Steps should be taken to ensure quality assurance in the services provided by the sector of early childhood education which presently operates on a semi-informal basis.

- Strengthen the existing institutional mechanisms maintained by the Provincial Councils by formulating national standards. A scheme for accreditation of service providers for early childhood education, along with licensing the institutions as well as teachers, should be designed.

- Streamline early childhood education with greater emphasis on training and professionalisation for service providers, particularly teachers.

- An institutional framework to monitor, support, improve, and sustain the sector of early childhood education should be introduced. An Early Childhood Education Authority should be established with a mandate to work in collaboration with Provincial Councils and Local Government bodies.

- The above can be implemented by taking the following steps: (a) the Government empower the Authority to formulate guidelines for teacher recruitment, training of teachers, formulation of syllabi and teaching methods, management of pre-schools, school space, and facilities and equipment needs; (b) this Authority vests some of these responsibilities in the Provincial Councils and Local Government bodies to be carried out under its supervision; (c) adding the kindergarten class into the national primary school system run by the State.

School education

Policy challenge: The crisis of school education sector is multi-faceted and pervasive. The school education sector is also influenced by a vast array of stakeholders with competing interests and agendas. Much needed structural reforms in this sector need to be carried out with strategies to manage resistance to reform by diverse interest groups. That requires sustained dialogue between policy-makers and groups who may have dissenting views.

Reform proposals

- Rethinking and reforming the social and policy utility of Grade Five Scholarship Examination: The Government should design in its place a new scheme, without its highly demanding, commercialised and oppressive examination mechanism. The new scheme should provide (a) enhanced financial assistance to needy children of low-income families and (b) better schools for meritorious and highly promising students within each province. Beneficiaries should be identified by means of a combination of national level examinations and improved, transparent, and abuse-free school-based assessments conducted within each province.

- Once the above (a) and (b) are implemented, a scholarship examination only for needy students and an admission examination for meritorious students from under-equipped rural and urban schools should be introduced.

- Restructuring the present GCE Advanced Level Examination: This should be done by introducing two examinations at Year 13. One examination will enable students to obtain national-level school leaving certificates for early employment and vocational training. The other examination will qualify students for higher education in universities and other higher educational institutions.

- Better vocational education for school leavers: Introduce on a priority basis a system of vocational education and training that are well-planned and sustainable for students leaving school after Year 13. It should aim at qualifying the school-leavers for employment in national and global labour markets. Financial collaboration from the private sector through public-private partnership should be secured for this since the private sector would be its primary beneficiary.

- Reorienting post-primary school education: The present system of post-primary education should be reoriented towards creatively integrating mathematics, science, social studies, civics, aesthetics, value education, English, and a Second National Language in the school curriculum.

- Restructuring GCE Advanced Level curriculum framework: Redesign the present scheme of GCE Advanced Level subject streams as Arts, Physical Science, Biological Science, Commerce, and Technology by (a) doing away with the existing system of strict compartmentalisation of subject streams and (b) making inter-stream mobility through a flexible system of course modules possible.

- The Advanced Level curriculum should be redesigned on the basis of a module-based credit system. The new system should enable preferred combinations of modules spread across core subjects and subsidiary subjects.

- Introducing student counselling: Make student advising and counselling mandatory in schools. Creative redesigning of senior secondary school education, as suggested above, necessarily requires the provision of student advising and counselling.

- Introducing value education: Reorient the school subject of Religion towards an emphasis on inter-religious value education. Religious education should focus on basic principles of philosophies and ethical doctrines, and not rituals, of major religions practiced by citizens of Sri Lanka. Appoint a committee of educationists to advice on what philosophical and ethical content of vast bodies of religious doctrines should be included in the limited school curricula in value education.

- Introducing the idea of career paths: Introduce from Year 10 onwards the idea of future career paths and career options to school children. It should enable parents, along with teachers, to begin to think about and plan the children’s futures positively and knowledgably.

- Strengthening career guidance in schools: Train and establish a special cadre of schoolteachers as qualified career guidance counsellors for schools. This calls for setting up an institute under the Education Ministry for training and accrediting schoolteachers for counselling and student advising.

- Retraining and empowering teachers: Initiate an accelerated programme of retraining and re-empowering all school teachers. Its activities can be done through stages and by means of decentralised initiatives with the participation of Provincial Councils. Such a program should aim at (a) updating and enhancing teachers’ subject knowledge and (b) equipping them with new methodologies of teaching, assessment, and mentoring.

- To make this more attractive and to compensate for their time, schoolteachers should be offered a better remuneration package plus a performance and training-related compensation-recognition system.

- Addressing the Year 13 student absenteeism: Take immediate administrative measures to ensure that students at Year 13 regularly attend school and that teachers conduct classes properly and diligently in the school for Year 13 students. This should aim at ending the present apathy and indifference shown by schoolteachers, principals, and Education Ministry towards the widespread problem of student absenteeism at Year 13.

- Regulating the private tuition industry: Introduce legislation to control and regularise the private tuition industry by the Education Ministry. It should aim at (a) minimising the share of family budget spent on education of children outside the school system, (b) restoring the lost norms of free education in the country in order to help low and middle-income families, (c) ensuring that provision of education is not exploitative, and (d) guaranteeing that undue burdens are not placed on students via excessive training and endless rote learning for examinations.

University education

Policy challenge: University education is the sector that has defied any major reform for change from its outdated goals, institutional structure, and organisational culture. Attempted and actual reforms in the university sector, from student admission to teaching programs and diversification of ownership, has led to political unrest and organised resistance too.

The sector is lagging behind the country’s changing needs. It has also been struggling to cope with new demands for change and reorientation emerging from national as well as global conditions. Radical and major reforms are required in the higher educational sector. Yet, they need to be introduced and managed with a focus on preventing disruptive consequences in the social and political spheres.

Reform proposals:

- Restructuring the university curricula in AHSS fields: Addressing the challenge of providing employment to increasing numbers of graduates in Arts, Humanities and Social Science fields as a major policy priority, universities should be encouraged to restructure undergraduate courses and curricula.

- Such restructuring should aim at directly qualifying graduates to diverse professions in State and non-State sectors while substantial subject knowledge is retained in undergraduate education. That should also aim at inculcating a more inclusive sense of public citizenship among graduates who at present feel alienated from society.

- Restructuring the university system: Consider restructuring the existing university system to formulate a clearly defined college system for undergraduate education and a university system for advanced training. The new focus should be on immediate employment with regard to training in the former and more advanced professional and academic training in the latter.

- Reforming the system of career-guidance: The MoHE, UGC, and universities should rethink the current emphasis on narrowly conceived soft-skills training programs through career guidance. Those existing programs should be strengthened through a synthesis of academic education with training for professional careers.

- Forecasting employment requirements of the economy: Initiate a mechanism for research-based forecasting of annual requirements for employment in different professional fields. This should be achieved in collaboration with the MoHE, UGC, the universities, Manpower and Employment Ministry, and Census and Statistics Department. That should enable the expansion of university education to be planned in conjunction with the changing realities of the labour market and trends in the global and national economies.

- Reforming undergraduate curricula: Encourage the UGC and universities to initiate curriculum reforms in the undergraduate education to enable students of all fields to receive and benefit from a broad-based and holistic education. It should aim at transcending the present frameworks of faculty and stream-based, and narrowly conceived, academic and disciplinary compartmentalisation.

- Reviewing and reforming the District Quota System: Review and revise the existing District Quota System for university admission. The new system should enable more students from poor and middle-income families of rural districts to enter Science, Medicine, Engineering, and Technology Faculties.

- Raising the quality and standards of teaching: Bring all systems of knowledge offered by universities at both undergraduate and postgraduate levels closer to clearly identified global norms and good practices. Similarly, offer adequate and closely monitored training programs for university teachers to ensure that they can offer the training to students at par with global norms and standards.

- Upgrading post-graduate education and training: Make it mandatory for State universities and non-State higher educational institutions to ensure that their post-graduate programs comply with authentic global norms in teaching, learning, training, research, and publication. This calls for mechanisms for monitoring to be in place.

- Upgrading the quality of external degree programs: Make it also mandatory for State universities to raise the quality and standards of the education provided to students in external degree courses and open and distance learning programs. This also requires mechanisms for monitoring to be in place.

- Professional training for graduates: Establish an institute for administrative and managerial training to enable university graduates to obtain professional qualifications required for executive and managerial professions in the State and non-State sectors. The Higher Education Ministry, UGC, Public Administration Ministry, Manpower and Employment Ministry, and the private sector should collaborate in this initiative.

- Setting-up of a university publishing and printing service: The nonexistence of a formal academic publishing industry in the country has negatively impacted the in-county production of serious knowledge. In order to address this issue, explore the possibility of creating at least one university-led non-profit publishing enterprise. It should be designed on the models of successful university presses elsewhere in the world.

- Regulating and standardising private educational institutions: Ensure that all private educational institutions adhere to norms and standards of quality in all their teaching and training programs, as will be set out by the UGC through appropriate regulations. This should be done through a mechanism of monitoring and compliance.

Tertiary and Vocational Education and Training (TVET) sector

Policy challenge: Modernising, upgrading, and strengthening of the TVET sector to make its doors open to large numbers of secondary school leavers is as important as the higher education sector. It is the sector that has untapped capacity and potential to help policy-makers resolve the perennial mismatch between education and employment. Modernising this sector requires new capital investment, greater international support, sustainable public-private partnerships, and institutional innovation.

Reform proposals

- Diversification of syllabi: Diversify the syllabi of TVET sector to accommodate new skills requirements necessitated by the Fourth Industrial Revolution. This should be done in collaboration with the International Labour Organization.

- Regulating the informal employment sector: Introduce a scheme under the National Vocational Qualification (NVQ) framework to gradually formalise the existing employment in the vast informal sector.

- It should cover transport, motor vehicle repair and maintenance, household-based industries, small manufacturing, domestic service, construction, retail trade, cleaning and sanitary service, private security industry, etc. Such a scheme should also aim at guaranteeing the employees better wages, labour entitlements, and working conditions while introducing both employers and workers to modern work-ethics.

- Incentives for vocational and technical trainees: Most TVET trainees are usually from low-income family backgrounds. They currently receive inadequate State financial support for survival. Provide the TVET trainees, in collaboration with State and non-State sectors, improved monthly allowances during their apprenticeship period. This should be viewed as an incentive for school leavers to join the TVET sector for vocational training and eventual employment.

- Upgrading skills of migrant workers: Upgrade and open the TVET sector to accommodate the currently unskilled migrant workers to Middle Eastern countries. Their skills should be updated to suit changes in labour requirements of a rapidly changing world of work.

- Training for female school leavers for non-traditional professions: Encourage more female school leavers to join the TVET sector. They should be provided training and employment opportunities beyond the vocations traditionally reserved for women. Making available to them incentives to build their careers in the fields of technology, engineering, IT etc., should also be a priority. A policy of affirmative action should be designed and implemented to achieve this objective.

(Professor Ratnasiri Arangala, Sri Jayawardenapura University; Dr. A. M Navaratna Bandara, Peradeniya University; Dr. Michael Fernando, formerly Peradeniya University; Wipula Karunathilake, Development Journalist; Dr. Mohammed Mahees, Colombo University; Professor Sasanka Perera, South Asian University, New Delhi; Professor Jayadeva Uyangoda, formerly Colombo University.)