Saturday Feb 28, 2026

Saturday Feb 28, 2026

Thursday, 31 January 2019 01:04 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

|

| By Thisali de Silva and Nisha Arunatilake |

The blue, green, red, and yellow three-wheelers navigating traffic or parked along the roads waiting for customers has become a common sight in any part of Sri Lanka. The large number of youth being employed as three-wheeler drivers has concerned policymakers, especially given the widespread labour shortages in a wide range of industries in the country.

The Government has tried to intervene in the tuk-tuk market by attempting to impose an age restriction on three-wheeler operators. The proponents of the age restriction cite careless driving practices of three-wheeler drivers, the increasing number of road accidents, and road congestions caused by unruly three-wheelers as the main reasons for such a regulation.

The lack of interest among youth to look for employment in sectors with labour shortages is also a concern. This blog attempts to clarify some myths about the three-wheeler market, while weighing in on the debate on whether the Government should impose an age restriction on three-wheel drivers.

What is the size of the tuk-tuk taxi driver market?

One argument for regulating the three-wheeler market is its size. Many newspaper articles in the past few months have made reference to more than one million three-wheelers on the road. But, careful examination of data shows that the number of three-wheelers available for hiring is much less.

It is true that the number of three-wheelers on the roads have increased over the years. The number of registered three-wheelers has increased by 372,740 from 2012 to 2017; in 2018 this number surpassed the one million mark. However, not all registered three-wheelers are hired. The 2013/14 Economic Census of the Department of Census and Statistics estimates that only 47% of registered three-wheelers are used as taxis.

On this basis, it can be estimated that there are only around half a million tuk-tuk drivers providing a taxi service in the country – much less than commonly assumed. This indicates that around 6% of the national labour force are tuk-tuk taxi drivers. However, not all of them are full time three-wheeler operators. In fact, three-wheeler operators are among the top ten secondary occupations in Sri Lanka.

As per labour force data, about 12% of three-wheeler drivers consider that as their secondary occupation. This means that the number of those employed in the three-wheeler market as full-timers is less than half of the one million figure that is often quoted.

Are tuk-tuk taxi operators mostly young?

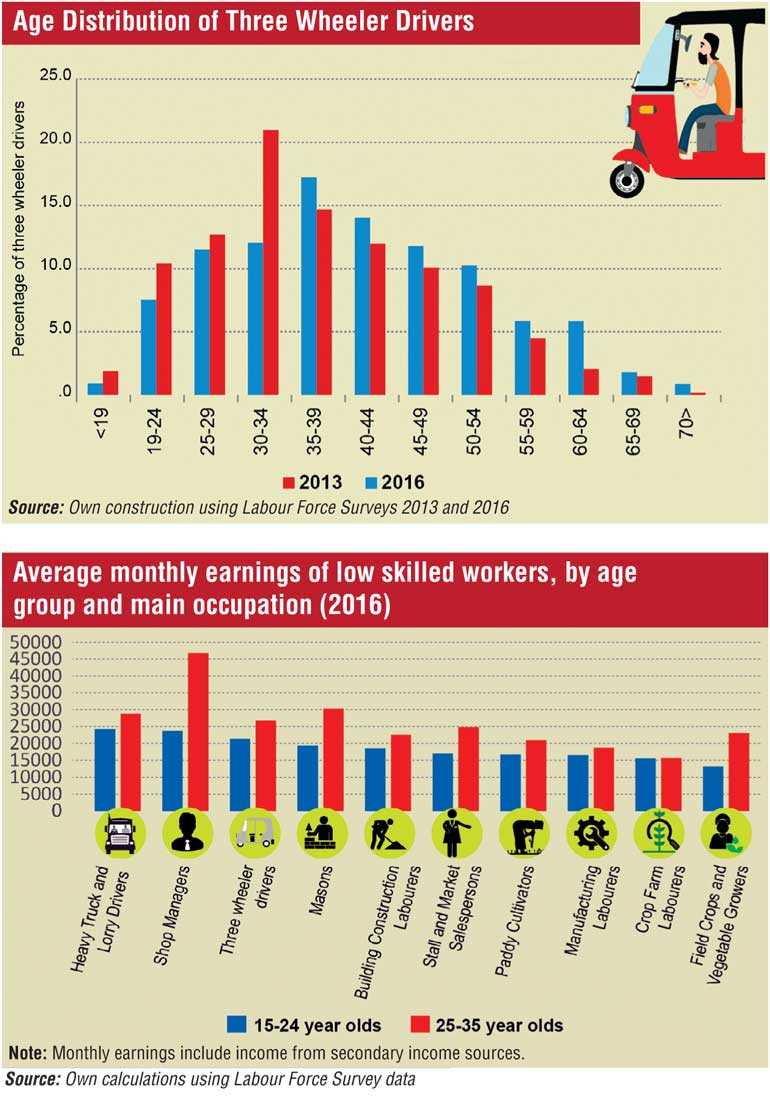

Apart from the sheer number of three-wheelers on the roads, another main concern of policymakers is that too many youth opt to drive three-wheelers, without obtaining other types of vocational training. However, labour force survey data (2016 and 2013) show that the largest share of three-wheeler drivers is found among middle-aged (30-40 years) individuals.

Further, the share of youth operating three-wheelers have decreased from 2013 to 2016 (see graph). As shown in the data, in 2016, the share of individuals in the three-wheeler market increases after age 35. This increase is more pronounced in 2016.

Who is attracted to the tuk-tuk market?

The three-wheeler market is most attractive to those with low levels of education. With males below 35 years of age with low skills, three-wheeler driving is in the top most occupied jobs. Most three-wheeler drivers (75.5%) have not passed G.C.E. Ordinary Levels and have not obtained any sort of formal vocational or industrial training.

Why are individuals attracted to the tuk-tuk market?

A qualitative analysis of tuk-tuk operators showed that many young school-leavers as well as middle aged people in Sri Lanka are attracted to the three-wheeler market due to many reasons. Young individuals enter into this market because it yields quick profits without allocating years on training or education. Middle-aged drivers seem to choose this occupation after quitting other formal jobs.

Some stated that they prefer three-wheeler driving mainly due to the low responsibility involved, compared to other jobs. Also, they enjoy having time for family commitments and not being confined to one place for large periods of time.

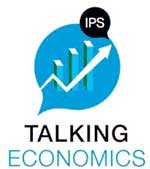

Another attraction of the three-wheeler market is the earnings. Three-wheeler driving was among the highest average monthly income earning occupations – only beaten by shop managers, masons, and heavy vehicle drivers. Further, the average monthly earnings of workers in other occupations who operated three-wheelers as a secondary income earning source was also very high. Long-term training and experience is needed to be successful in some of these high remuneration occupations such as masonry or heavy vehicle driving. Meanwhile, some three-wheeler drivers chose this occupation to finance other entrepreneurial activities.

Some three-wheeler operators have tried other occupational avenues, such as working in factories and as helpers in shops, before becoming tuk-tuk drivers. But, those jobs were not attractive to them as they were low paying, high stress and/or had inflexible work hours.

What are the policy implications?

The above data shows that low skilled youth are attracted to the three-wheeler market as it provides better earnings and attractive working conditions such as flexible hours and low stress. Many are attracted to the three-wheeler market to supplement their incomes from their main job or to finance other business activities. Imposing an age barrier on entering the three-wheeler market would deny youth the opportunity to earn an additional living.

If safety and undisciplined driving is a concern, stricter regulation for providing three-wheeler licensing that require training in safe driving and road rules would result in reducing three-wheeler related accidents, traffic violations, and road safety concerns. This analysis also indicates that better wages and better working conditions can be helpful in attracting youth to industries experiencing labour shortages.

[Thisali de Silva, Project Intern at the Institute of Policy Studies of Sri Lanka (IPS) was the recipient of the Saman Kelegama Memorial Research Grant 2018. This blog is a part of her research work carried out with the grant under the supervision of Nisha Arunatilake, Director of Research, IPS ([email protected]). To view this article online and to share your comments, visit the IPS Blog ‘Talking Economics’ - http://www.ips.lk/talkingeconomics/]