Tuesday Feb 24, 2026

Tuesday Feb 24, 2026

Monday, 16 October 2023 00:53 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Yan Carrière-Swallow and Krishna Srinivasan

www.imf.org/en/Blogs: Strong consumer spending has supported growth in Asia’s three largest economies this year, but there are already signs that the region’s recovery may be running out of steam.

www.imf.org/en/Blogs: Strong consumer spending has supported growth in Asia’s three largest economies this year, but there are already signs that the region’s recovery may be running out of steam.

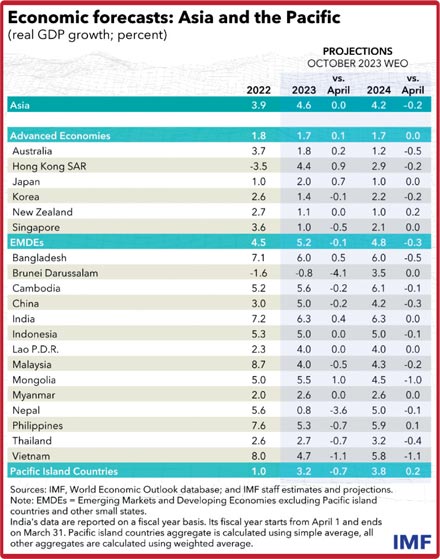

We expect growth in Asia and the Pacific to accelerate from 3.9% in 2022 to 4.6% this year, unchanged from the projection from last April. This is largely explained by the post-reopening recovery in China and stronger-than-expected growth in the first half of the year in Japan and India. With pandemic restrictions lifted, demand in these economies was bolstered by consumers running down savings accumulated during the pandemic, leading to notable strength in the services sector.

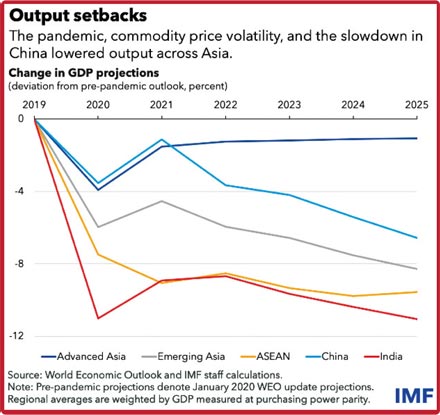

While Asia is still set to contribute about two-thirds of all global growth this year, it is important to note that growth is significantly lower than what was projected before the pandemic and output has been set back by a series of global shocks.

We have lowered our estimate for growth next year to 4.2%, from the 4.4% projected in April. Our less-optimistic assessment is based on signs of slowing growth and investment in the third quarter, in part reflecting weaker external demand as the global economy slows, such as in Southeast Asia and Japan, and faltering real estate investment in China.

The economic boost that China enjoyed after its re-opening is now losing momentum earlier than previously expected. While we project the rebound will underpin growth quickening to 5% this year, the economy would slow to 4.2% next year amid the deepening property-sector slump, down from the 4.5% we had forecast in April.

The economic boost that China enjoyed after its re-opening is now losing momentum earlier than previously expected. While we project the rebound will underpin growth quickening to 5% this year, the economy would slow to 4.2% next year amid the deepening property-sector slump, down from the 4.5% we had forecast in April.

The drag from China would historically have been offset by forecasts for faster growth in the United States and Japan, but the resulting boost is likely to be more muted this time. The strength of the US economy has been focused in the service sector, rather than in goods, which doesn’t fuel greater demand for Asia. And US policies such as the Inflation Reduction Act and CHIPS and Science Act are re-orienting demand toward domestic sources rather than foreign, providing a smaller boost to imports from Asia.

In the near term, the sharp adjustment in China’s heavily indebted property sector and the resulting slowdown in economic activity will likely spill over to the region, particularly to commodity exporters with close trade links to China. Beyond this, an aging population and slowing productivity growth will further temper growth over the medium-term in China, amid rising risks of geo-economic fragmentation, and bear upon prospects in the rest of Asia and beyond. In a downside scenario where “de-risking” and “re-shoring” strategies take hold, output could decline by up to 10% over five years in the Asian economies most closely linked to China’s economy.

In the near term, the sharp adjustment in China’s heavily indebted property sector and the resulting slowdown in economic activity will likely spill over to the region, particularly to commodity exporters with close trade links to China. Beyond this, an aging population and slowing productivity growth will further temper growth over the medium-term in China, amid rising risks of geo-economic fragmentation, and bear upon prospects in the rest of Asia and beyond. In a downside scenario where “de-risking” and “re-shoring” strategies take hold, output could decline by up to 10% over five years in the Asian economies most closely linked to China’s economy.

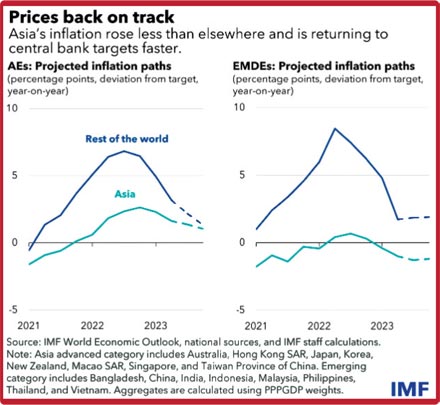

A welcome development is that disinflation is on track in Asia, with inflation now expected to return to central bank target ranges next year in most countries. This process is well ahead of most other regions, where inflation remains high and is expected to fall within target only in 2025.

As we described in a 2021 blog post, the post-pandemic inflation surge had divergent effects across Asia – a topic we revisit in-depth in our forthcoming Regional Economic Outlook. Some countries such as Indonesia have already brought overall and core inflation back to target after substantial increases last year. In contrast, inflation in China is below target and – with demand sluggish amid deepening stress emanating from the property sector – is expected to rise only gradually due to policy stimulus.

Inflation has risen in Japan, where the central bank has twice tweaked its yield curve control policy settings to manage risks to the outlook. Given the large participation of Japanese investors in global markets, we find that these policy actions led to spill overs in other bond markets. These could become larger in the event of a more substantial normalisation of monetary policy in the region’s second-largest economy.

The global environment remains highly uncertain, and while risks to the outlook are more balanced than they were six months ago, Asia’s policymakers must stay the course to ensure continued growth and stability. On the downside, a more protracted real estate crisis and limited policy response in China would deepen the regional slowdown. And a sudden tightening of global financial conditions could lead to capital outflows and put pressure on Asia’s exchange rates that would threaten the disinflation process.

Countries with inflation still above targets, such as Australia, New Zealand, and the Philippines, should continue to signal a commitment to reducing inflation. This will entail maintaining restrictive monetary policy until inflation durably falls to target and expectations are firmly re-anchored.

In many of the region’s emerging market and developing economies, including Indonesia and Thailand, financial conditions have remained relatively accommodative and real policy rates remain close to neutral levels, reducing the need for an early loosening of monetary policy.

Where tight monetary conditions are straining financial stability – including through the real estate sector and heavily indebted companies – supervisors must monitor systemic risks closely. And with public debt still high across most of the region, the ongoing gradual fiscal consolidation should continue to build room for manoeuvre and to ensure debt sustainability. For those emerging market and developing economies like Sri Lanka that are suffering from funding stress on external markets, faster and more efficient coordination on debt resolution is needed.

As long-term prospects dim, countries must redouble their efforts to advance growth-enhancing reforms. Raising government revenue ratios from low levels would allow for additional spending on important needs such as education and infrastructure, while keeping public debt in check. Finally, strengthening multilateral and regional cooperation and mitigating the effects of geo-economic fragmentation are increasingly vital for Asia’s economic outlook in coming years. To that end, reforms that lower nontariff trade barriers, boost connectivity, and improve business environments are essential to attract more foreign and domestic investment across the region.