Monday Feb 16, 2026

Monday Feb 16, 2026

Tuesday, 7 September 2021 01:25 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Macroeconomic stability is crucial to sustain economic growth. The International Monetary Fund (IMF), which is known as the ‘global financial firefighter,’ provides support to its member countries that have problems with internal stability (inflation) and external stability (balance of payments, exchange rate, foreign indebtedness and international reserves).

Macroeconomic stability is crucial to sustain economic growth. The International Monetary Fund (IMF), which is known as the ‘global financial firefighter,’ provides support to its member countries that have problems with internal stability (inflation) and external stability (balance of payments, exchange rate, foreign indebtedness and international reserves).

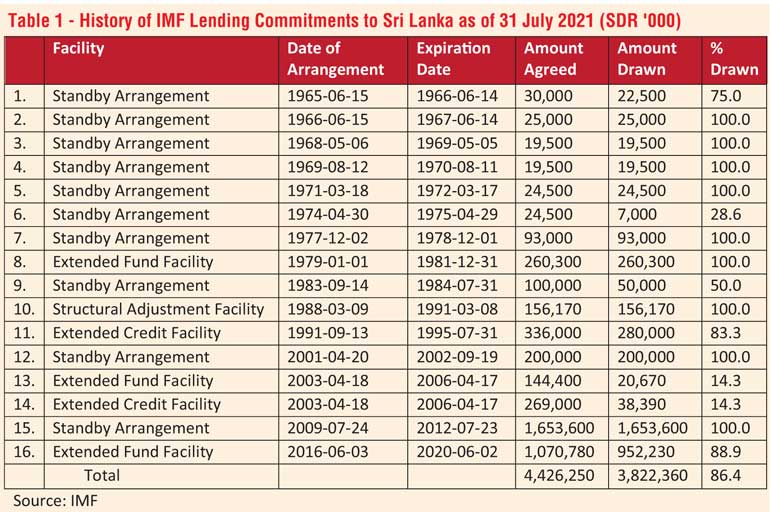

Being a member of the IMF since 1950, Sri Lanka has obtained its assistance through different facilities on 16 occasions to tackle the economic difficulties from 1965 onwards (Table 1).

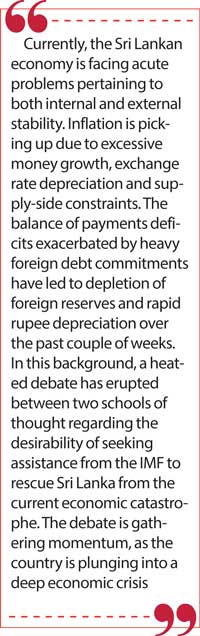

Currently, the Sri Lankan economy is facing acute problems pertaining to both internal and external stability. Inflation is picking up due to excessive money growth, exchange rate depreciation and supply-side constraints. The balance of payments deficits exacerbated by heavy foreign debt commitments have led to depletion of foreign reserves and rapid rupee depreciation over the past couple of weeks.

Debate: For and against IMF

In this background, a heated debate has erupted between two schools of thought regarding the desirability of seeking assistance from the IMF to rescue Sri Lanka from the current economic catastrophe. The debate is gathering momentum, as the country is plunging into a deep economic crisis.

The proponents of IMF programs, who are mostly outside the official arena, argue that such assistance is essential to eliminate the country’s macroeconomic imbalances, and to resolve the debt crisis, and thereby to boost investor confidence. There is urgent need to adopt IMF-styled policy reforms to put the house in order so as to overcome the present crisis, as I emphasised in a recent FT column (https://www.ft.lk/columns/Denying-IMF-support-is-no-solution-for-Sri-Lanka-s-economic-woes/4-721234).

On the contrary, the opponents assert that the IMF programs implemented in Sri Lanka from time to time worsened the country’s economic problems due to their vicious conditionalities. They accuse that those programs are based on neoliberalism, which is resurgence of free-market capitalism that was in vogue in the 19th century.

Policymakers avert IMF

The top policymakers of the Government and the Central Bank are claiming that they are in a position to overcome the current economic problems without resorting to the IMF by adopting a home-grown alternative strategy. The Central Bank, which is the apex monetary body set up to ensure macroeconomic stability, is taking a hardline to avert IMF assistance without any sound justification.

In the backdrop of the ongoing controversy, it would be pertinent to look at the rationale behind IMF assistance objectively from the viewpoint of national interest, leaving aside any emotional attachments to a particular line of ideology or personal affiliations with individuals who are in the corridors of power.

IMF Monetary Model

The IMF’s model of macroeconomic stabilisation is based on a framework, known as the “monetary approach to balance of payments”. This model was developed in 1957 by Jaques J. Polak, who functioned as the Research Director of the IMF during 1958-1979. He is considered as the founder of the monetary model that the IMF has applied to date, and therefore, it is also known as the Polak model. The IMF applies financial programming based on the Polak model to assess the impact of a borrowing country’s Government finances and foreign reserves on its economic growth, money supply, inflation and balance of payments.

In its simplest form, the model investigates and determines the impact of changes in (a) domestic bank credit, and (b) exports and imports of goods and services on the money supply, and in turn, on inflation, income and balance of payments. Given the significant impact of government borrowings on domestic bank credit and money supply, pruning the budget deficit through expenditure cuts is a key conditionality in IMF’s lending programs.

Similarly, the balance of payments deficit is required to be brought down by bringing down the money supply growth, and ensuring a competitive exchange rate system. These are the basic conditionalities of the Fund’s programs, which are always subject to severe attack by the critics.

The IMF’s financial programming integrates monetary, fiscal, external and real sectors into a single quantifiable framework. This model is used to identify the types of macroeconomic policies that are required to achieve final targets such as the inflation rate and foreign reserves of countries that require IMF support to overcome their macroeconomic instability.

SL’s economic imbalances

Sri Lanka now faces both internal and external imbalances. Internally, the budget deficit running over 12% of GDP limits monetary policy space, resulting in an increase in the money supply by 21% over the last 12 months. The rapid money supply growth has brought about adverse consequences on price stability and balance of payments.

Externally, the country’s foreign reserves have fallen to less than $ 3 billion, as against the debt commitments of over $ 6 billion to be settled within the next 12 months, apart from having to meet day-to-day import outlays. The banking sector is running short of foreign exchange. As a result, the US dollar is traded at around Rs. 230 within the banking circles, despite the Central Bank’s insistence to keep it at Rs. 200 per dollar. The black-market rate is reported to be high as much as Rs. 260 per dollar.

IMF-styled measures in piecemeal

The lack of an IMF-styled macroeconomic framework is the root cause of most of the macroeconomic imbalances faced by Sri Lanka today.

The policymakers are now compelled to adopt some arbitrarily chosen IMF-styled measures such as monetary tightening, rupee depreciation, Government expenditure cuts and fuel price hikes, despite their resistance to approach the IMF. But such piecemeal measures fail to overcome the crisis, as they are not integrated into a unified monetary model described above.

Obsolete import restrictions reintroduced

Obsolete import restrictions reintroduced

As remedial measures, import restrictions in the form of quantitative restrictions (QRs), quotas, licenses and exchange controls are back in full swing. The outcomes are price controls, food shortages, long queues, monopolies, rising prices, black market, raids, and corruption, that we witness today. These were the characteristics of controlled trade regimes adopted in many developing countries including Sri Lanka around four decades ago.

The restrictive trade policies adopted prior to 1977 in Sri Lanka could be justified today at least on the grounds that those policies were based on the “import substitution” argument, which was the paradigm accepted worldwide during that time. But as trade liberalisation has enabled numerous countries across the world to accelerate economic growth and to reduce poverty levels significantly in recent decades, import substitution became obsolete many years ago.

Policy reforms under EFF (2016-2020)

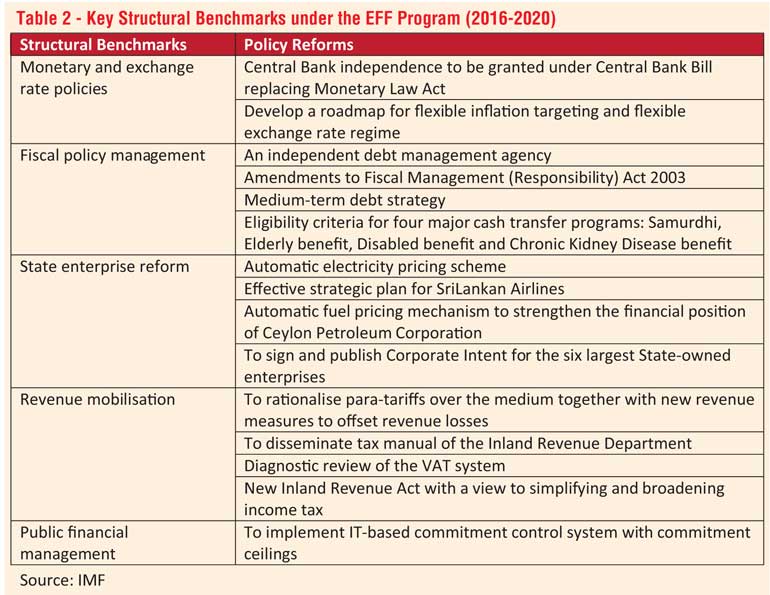

The last facility obtained by Sri Lanka from the IMF was under the Extended Fund Facility (EFF) for the period 2016-2020. It contained a set of policy reforms that could have prevented the present macroeconomic instability to a large extent (Table 2).

Fiscal consolidation with targeted reduction of the overall fiscal deficit was the linchpin of the EFF program. Rebuilding tax revenues through comprehensive reforms of both tax policy and administration were key in this regard. Those were to be supplemented by steps toward more effective control over expenditures and putting state enterprise operations on a more commercial footing.

Another major policy reform in the EFF was to replace the Monetary Law Act with a new Central Bank Act so as to provide greater independence to the Central Bank by permitting it to adopt inflation targeting monetary policy. It would have restricted the Central Bank’s accommodation of fiscal shortfalls and the resulting money supply growth, as experienced now.

Policy reforms scrapped

The present Government scrapped the EFF arrangement without drawing its last tranche. Aggressive tax cuts were implemented last year, and the fiscal policy targets were postponed until 2030. The Central Bank Bill was abolished. Thus, the envisaged EFF policy reforms were abandoned, and as a result, the macroeconomic situation has worsened.

The outcome of the revenue downfall resulted from the tax cuts was the rise in the budget deficit to over 12% of GDP. Being subservient to the political authorities, the Central Bank has accommodated Treasury’s cash requirements which led to an unprecedented increase in currency issues and bank credit to the Government.

The resulting monetary expansion created enormous demand pressures on the price level and imports. With the rapid depreciation of the rupee reflecting divergent exchange rates within the banking sector, the black market is thriving with exorbitant dollar rates.

Reforms imperative with or without IMF

The economic turmoil that we are experiencing today could have been avoided, had the policy reforms laid down in the EFF been continued without interruption, irrespective of political divisions.

The present economic catastrophe speaks for itself justifying the urgent need of a robust policy framework, with or without IMF assistance, to tackle the macroeconomic imbalances.

(The writer is Emeritus Professor of Economics at the Open University of Sri Lanka and a former Director of Statistics, Central Bank of Sri Lanka. He is a Senior Visiting Fellow of the Advocata Institute, reachable at [email protected])