Saturday Feb 21, 2026

Saturday Feb 21, 2026

Saturday, 29 June 2019 00:01 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Dylan Perera

By Dylan Perera

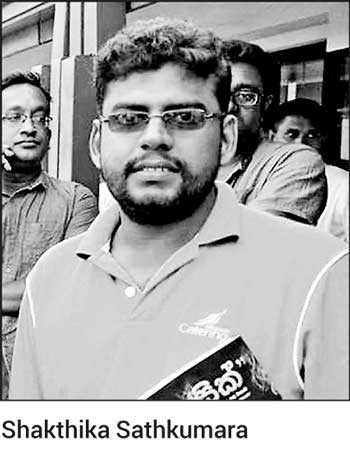

For the last 11 weeks Shakthika Sathkumara, an award-winning creative writer, has been deprived of his liberty by the State, for what appears to be the crime of blasphemy. Apart from posing an existential threat to artistic expression, his imprisonment also gravely undermines the quintessential spirit of the Buddha’s doctrine.

Blasphemy is a firmly established concept in Abrahamic religions, where the idea of causing offence to some inviolable, sacred object or person has been honed and executed by religious institutions for millennia. For instance, the book of Leviticus in the Bible’s Old Testament airily prescribes stoning as a punishment for blasphemy.

More recently the former Iranian leader and cleric Ayatollah Khomeini, in similar vein, called for the death of author Salam Rushdie whose bestselling book Satanic Verses was deemed blasphemous.

Not to be outdone, Catholics and the Evangelical right found Martin Scorsese’s classic film ‘The Last Temptation of Christ’ blasphemous – though they stopped well short of seeking his death. While most religions quickly move to sacralise aspects, ideas or rituals accompanied by prohibitions articulated in the central sacred texts – Buddhism has until now remained a striking exception.

In Buddhism unlike other religions of the world, the idea of blasphemy is entirely and unsurprisingly absent. It is an absence that is possibly best explained by that curious and appealing word Ehipassiko – the invitation to investigate and evaluate the Buddhist doctrine.

Ehipassiko makes no monopolistic or exclusive claim on the truth, no divine revelation, no elected human agent, no threats of death or damnation, no guilt edged promise of a special afterlife. It is a gentle but intellectually assured invitation to the reasoning mind with a confidence that dispenses with the politics of insecurity – meaning ‘come and see’.

Blasphemy is antithetical to Buddhism for another reason. In its thoroughly modern humanism, Buddhism empowers the individual, with his capacity for critical reasoning and willpower, to be at the center of the liberation project. When critical reasoning (articulated in the Kalama Sutta) supplants divine revelation as the chief tool in seeking knowledge and understanding, it necessarily has to be accompanied by the freedom to think, question, argue and express one’s self.

Unlike other religions Buddhism does not prescribe what is right thought, speech or action. Instead it offers a robust analytical framework to assess right thought, action and speech. The onus and freedom to determine what is right lies with the individual. The fact that people have differing ideas of the truth and the acceptance of the plurality of truths is brought out most extraordinarily in the Kimsukha Sutta.

It is perhaps because of this noisy (and chaotic) freedom of expression that, more so perhaps than any other religion, Buddhism has devoted so much of its founding doctrinal texts to detailing dispute resolution mechanisms. The Samagama Sutta is an entire discourse on conflict management – and again vitally modern in its approach. It commences with a root cause analysis deeply resonant with modern conflict resolution theory and offers seven working models for the settlement of disputes (see G.A. Somratne’s excellent essay on ‘Ancient Methods of Resolving Conflict’).

In this light, depriving a writer of his liberty for expressing an idea about Buddhism is not only damaging to the very central tenet of the Buddha’s emancipatory venture, it is deeply antithetical to the Buddhist approach to knowledge and intellectual disputes. In fact, the Buddhist commentary decries the heavy handed ‘balavamhi balavattho’ – might is right, approach taken by agents of the State in depriving Sathkumara of his liberty.

In the Vinaya Pitaka, which deals in thoroughly legalistic detail with misdemeanours, infringements and crimes in the Sangha, the intention behind the act is a matter of vital importance when evaluating positive actions from negative ones. (It is worth noting in passing that 5th Century B.C. Buddhist clerical jurisprudence is in perfect congruence with modern criminal law in its separation of the intention of a crime from the physical action when assessing culpability).

Intentionality is so central to Buddhist virtue that the Buddha started off his son Rahula’s Buddhist education with this idea. There is sadly no discussion at all about Sathkumara’s artistic intentions or purpose. What indeed would the Buddha have made of Sri Lankan Buddhists.

This primitive, dangerous and alien idea of blasphemy, based on unreasoning fear and an anxious need to protect, is fast creeping into mainstream Buddhism. It threatens the fundamental tenets of the Dhamma – that of the individual’s right to exercise free will and the freedom to discuss ideas – without which Buddhism rapidly degenerates from a sublime rationalism into a mindless dark superstition dressed in empty ritual.

The thinking Buddhist in the parliament, the judiciary and the Attorney General’s department should reflect on how to skilfully protect and sustain the invaluable doctrine of the Buddha from the insecurities of the so-called protectors of Buddhism.

They should also free us from the ugly stain of having ‘prisoners of Buddhism’ like Sathkumara – otherwise before we know it, we might have a ‘Buddhist section’ in our prisons as well as in our constitution and cemeteries.