Saturday Feb 28, 2026

Saturday Feb 28, 2026

Thursday, 12 December 2024 00:24 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

In sports, underperforming men are not accused of being feminine – it is the over performing females who capture the limelight

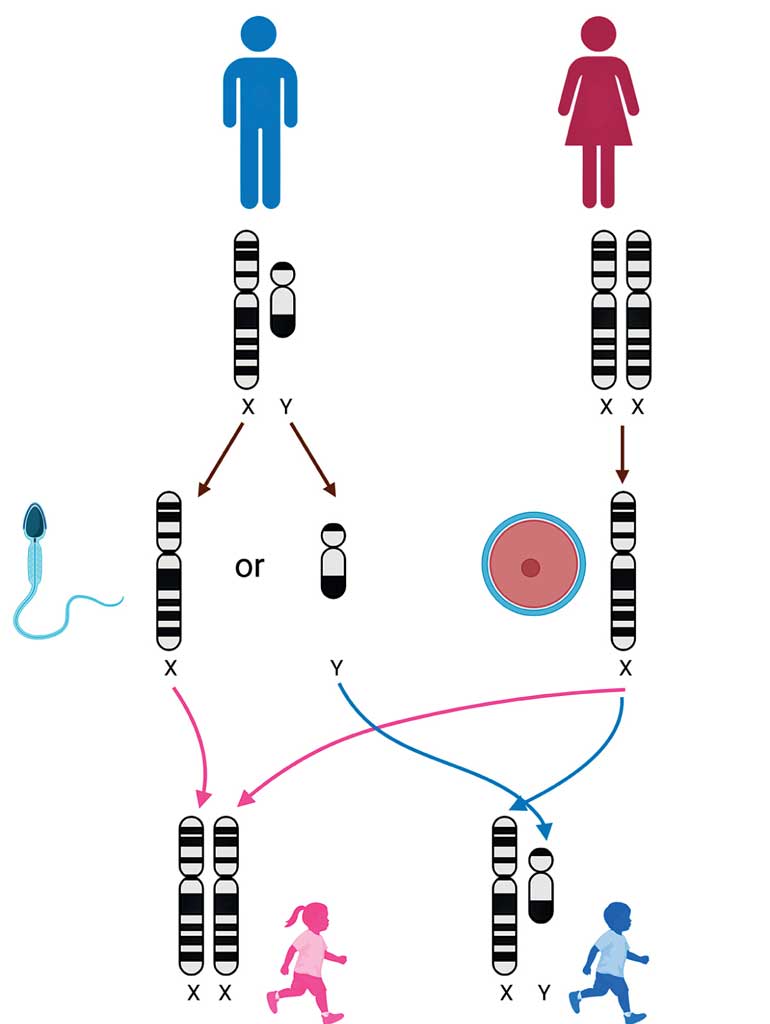

Figure: The inheritance of sex chromosomes from the parents

The binary division of boys and girls is similar to black and white to most of us. However, the controversy at the 2024 Olympics in Paris, in the boxing category for women, has raised questions regarding the sex of the Algerian boxer Imane Khelif and the Taiwanese boxer Lin Yu-ting. The controversy flared up when Imane Khelif competed against the Italian boxer, Angela Carini, who quit the fight after just 46 seconds saying that she had never been hit so hard in her boxing career.

The binary division of boys and girls is similar to black and white to most of us. However, the controversy at the 2024 Olympics in Paris, in the boxing category for women, has raised questions regarding the sex of the Algerian boxer Imane Khelif and the Taiwanese boxer Lin Yu-ting. The controversy flared up when Imane Khelif competed against the Italian boxer, Angela Carini, who quit the fight after just 46 seconds saying that she had never been hit so hard in her boxing career.

The Olympics brings out the best in the sporting abilities of humans, categorised into men and women. Each Olympic event features unforgettable performances both on and off the field. The 2024 Olympics was no different bringing to the spotlight a seemingly frivolous question: the definition for man and woman! The boxing ring saw Algerian Imane Khelif and Taiwanese Lin Yu-ting, who had previously failed a gender test by the International Boxing Association and were disqualified from taking part in the 2023 Women’s World championship. The two boxers were, however, cleared by the International Olympic Committee (IOC) to compete in the Paris games since they were given the female sex at birth. Obviously they were not men masquerading as women to pick up a medal. As always, when faced with a crisis, one turns to science to provide clarity and answers.

Boy or a girl? The sex chromosomes

So, let us explore the question what determines whether a baby will be born a girl or a boy. The simple answer lies in the pair of sex chromosomes within our cells. This discovery was made by Nettie Stevens, a schoolteacher, born in 1861 in Vermont USA. Unlike many other women of her time, Nettie opted for a university education and studied biology at Stanford University in California. She was particularly intrigued by how the male and female sexes was determined. She decided to look at the chromosomes, and out of all things, those of the mealworm beetle. Nettie stained the cells of the male and female mealworms. The blue-stained chromosomes showed a clear difference under the microscope. The mealworm has 10 pairs of chromosomes. The female mealworm had paired chromosomes while the male mealworms had an unusual pair: one chromosome was large and the other small. She suggested that the small chromosome determined the male sex. With this simple experiment Nettie Stevens had successfully discovered the sex chromosomes.

Genes, chromosomes and mutations

Let’s take a closer look at this. The bodies of all living organisms are composed of tiny units called cells. The genetic instructions for the development and functioning of our cells, and hence our bodies, are written in the long DNA strands, which are found coiled up in the chromosomes. These instructions are known as genes. Our physical characters and what goes on inside our body (or cells) are determined by our genes. They provide instructions to the machinery within our cells (chemical processes) to carry out the multitude of tasks necessary to sustain life – from determining the colour of our eyes and skin to guiding our development and growth.

Occasionally changes occur in our DNA. These changes (called mutations) are necessary for the diversity of life around us and for life to evolve. Mutations can also be undesired such as the mutation that created the coronavirus, which brought life to a standstill for many and tragic consequences for others.

Our genome

In humans, each cell has 23 pairs of chromosomes totalling 46 chromosomes; this is called our genome. We inherit two copies of the genome, one from our mom and one from our dad, forming the 23 pairs of chromosomes. Of these pairs, 22 are similar in length. However, the 23rd pair is different in males: the larger is called the X chromosome and the smaller is called the Y chromosome. This pair is known as the sex chromosomes. The genes on these chromosomes determine whether the baby develops male or female reproductive organs.

Eggs and sperm have only half the number of chromosomes present in other body cells. When sperm (in males) or egg cells (in females) are formed, they receive one chromosome each from the 23 pairs of chromosomes in the cell. Since males have a pair of XY chromosomes their sperm cells can have either an X or a Y chromosome (see Figure). Females have a pair of XX chromosomes, so their eggs can have only an X chromosome. When the egg and sperm cells come together during fertilisation, either a new XX or an XY pair is formed (see Figure). The sex of the baby to be born is determined while the foetus is developing in the womb. The Y chromosome in males is a sign of maleness. So, boys have a pair of XY chromosomes and girls have a pair of XX chromosomes.

Boy or girl?

There are many genes on the Y chromosome that provide instructions for male sex development. Among them, a crucial gene called the Sry (sex-determining region on the Y chromosome) gene sets in motion the instructions to determine our sex. This process occurs in the developing embryo in the mother’s womb around eight weeks after conception. The Sry gene carries the genetic information to produce the SRY protein. During normal embryonic development, the SRY protein initiates a cascade of events that result in the formation of the testis while suppressing the development of ovaries and female sex organs, leading to male sex differentiation. Thus, in the absence of the Y chromosome, the foetus (the embryo is called a foetus after 10 weeks of pregnancy) develops into a female. This is the normal development leading to boys and girls.

Once the Sry gene is activated, the foetus also produces sex associated signalling chemicals called sex hormones to signal the development of the male sex organs and maleness of the baby while still in the womb. This is the normal plan.

In a tiny fraction of people, things do not go according to the normal plan.

Swyer syndrome

In 1955, Dr. Gerald Swyer, a British physician (1917-1995) and a researcher in women’s health described a seemingly clinical paradox: individuals with a male pair of sex chromosomes (XY) but with female reproductive structures. This condition is called XY sex reversal. These individuals typically have a uterus and fallopian tubes, but their gonads (ovaries) do not function. Because they have female genital organs, babies born with Swyer syndrome, are raised as girls and develop a female gender identity. There is a case of a woman from Croatia with XY chromosomes who gave birth to two children. There are many more cases of women (with XY) who have given birth who do not always get themselves genetically tested.

The SRY gene

Pioneering work on sex chromosomes and the Sry gene was conducted by Prof. Jenny Graves of La Trobe University in Australia. Although the SRY protein is the master regulator of male sex development, the mere presence of the Sry gene or the Y chromosome does not guarantee maleness. According to Prof. Graves, there are several other genes involved in the process between the activation of the Sry gene and the development of the male sex organs. Consequently, changes or variations in any of these genes can result in changes in the expression of maleness.

In rare instances, the Sry gene may be lost from the Y chromosome in individuals born with an XY pair of chromosomes. These individuals would not produce the male hormone (testosterone) and would develop a female anatomy. Therefore, the presence of the Y chromosome in these cases does not imply maleness. Although testosterone is a hormone primarily produced by the testes in males, females also need it in low levels, which is produced by their ovaries. Typical testosterone levels in adult males range from 265 to 900 nanograms/dL and in females they range from 15 to 70 nanograms/dL.

Differences in sex development

There are many genes on the Y chromosome that provide instructions for male sex development. If any of the genes, associated with maleness, are defective such as due to a mutation, then there may be differences in sex development while the baby is still in the womb. For instance, if the Sry gene on the Y chromosome is not functional, the baby will develop female reproductive structures resulting in XY individuals with female sex organs. Thus, within this binary classification of boys and girls are a minority of individuals who have differences in sex development (called DSDs), which can manifest in society or in the sports arena. For this small minority the details of the Y chromosome are important. The Y chromosome may not be fully formed or there can be genetic material (parts of the DNA) altered or missing, which can be the cause of the DSD.

These defects are rare and diverse, which is why most of us are easily classified as males and females. For this very small minority, the typical rule of the Y chromosome determining the male gender, and the absence of a Y chromosome indicating a female, does not apply. It should be emphasised, that this only applies to a very small minority.

Defective genes

The changes in the genes (mutations) that cause them to malfunction can be very subtle. Science is now able to unravel these mysteries at the level of molecules. Research done at the Indiana University School of Medicine in the USA has revealed that a slight mutation in the Sry gene, which results in the replacement of one amino acid with another closely related amino acid (tyrosine with phenylalanine) in the SRY protein, weakens the formation of a SRY protein-DNA complex. This impairs the SRY protein’s ability to activate male sex differentiation.

There is no single test that can unambiguously classify an individual as male or female. For example, a female with a Y chromosome and an Sry gene, but with only some male-related genes activated, will not have any genetic advantage over a typical XX female. Given the biological variability that exists, even in a small fraction of the population, it seems unlikely that science can come up with a simple formula to define boys and girls, for this small fraction!

Socio-cultural aspects

In sports, underperforming men are not accused of being feminine – it is the over performing females who capture the limelight. In elite sports such as the Olympics, athletics, tennis, etc., it is usually the coloured females whose performance raise questions. For the layman, sex is an anatomical feature recognisable by male and female reproductive organs. However, as we have seen above, genetics, hormones and physiology are involved that should be considered. The term ‘gender’ is another story, overlapping with sex but involving gender identity, behaviour, social and cultural expectations. Gender applies only to humans – not to animals!

The game of science

Science in general and biology in particular has a lot of secrets. Figuring out these secrets is what scientists are up to. Richard Feynman is a celebrated physicist, teacher and Nobel Laureate. According to him, what is going on in the natural world is a game played by the gods! We humans do not know the rules of the game. But we can watch the game endlessly and figure out all or some of the rules. These are the laws in the natural world (Newton’s laws, Einstein’s hypothesis, Darwin’s theory of evolution, to name a few) which scientists are eternally trying to figure out. Even if we know all the rules there are exceptions waiting to confound us. To quote Jenny Graves, “Science is a very creative discipline; it requires you to think creatively to outwit nature and find out the secrets.”

(This article is based on material available in the public domain. The writer is a retired scientist, keen on popularising science to the public. He can be reached at [email protected].)