Tuesday Feb 17, 2026

Tuesday Feb 17, 2026

Tuesday, 17 April 2018 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Shashik Dhanushka and Andi Schubert

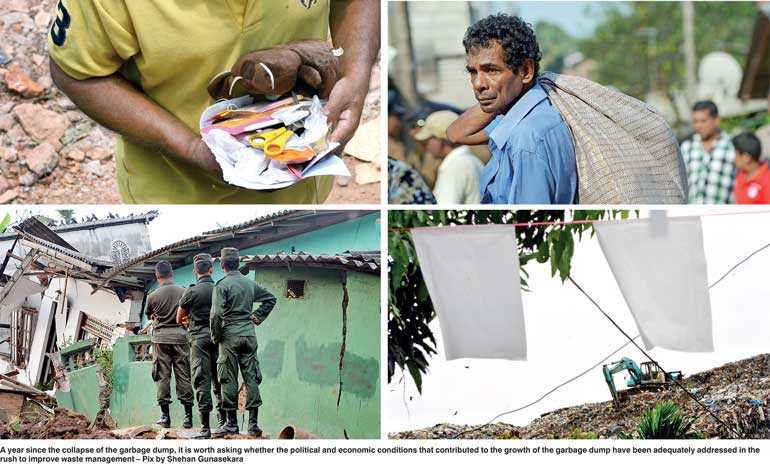

Saturday, 14 April, marked a year since the collapse of the garbage dump at Meethotamulla. Thirty-two lives were lost and nearly 60 houses were destroyed on that fateful New Year’s Day.

In the immediate aftermath of the tragedy much was said about the need for better waste management. Companies and the Government took steps to encourage more environmentally-friendly consumption habits. Alternative dumping sites have been explored and set up. The most recent Budget by Finance Minister Mangala Samaraweera also took steps to incentivise better waste management. However, the conditions that enabled the Meethotamulla tragedy continue to be buried in the rush to focus on better waste management.

To commemorate the first-year anniversary of the disaster, we take this opportunity to draw attention to the social injustice that enabled, quickened, and culminated in the collapse of the garbage dump.

When we spoke to those most deeply affected by the collapse of the garbage dump, they drew our attention to much deeper questions about the function of justice in our society. They challenged us to consider the cost they had to bear for the beautification of Colombo city. They demanded justice for the violence they faced from both the State and extra-state actors who violently suppressed their demonstrations against the dumping of garbage. And they broke down as they detailed how their miseries were exploited and losses monetised by political elements.

In this short article, we take their concerns seriously and hope to peel away the sanctimonious invocations of environmental conservation to discuss the question of injustice that has largely been ignored in conversations about the tragedy. ‘Kolamba Kunu Apata Epa’

‘Kolamba Kunu Apata Epa’ was the primary campaign slogan of the People’s Movement Against the Meethotamulla, Kolonnawa Garbage Dump. This slogan captures their desire to question as to why residents of Kolonnawa should bear the burden of Colombo’s excessive consumption habits and incapacity to manage their waste.

One of the responses of the Sri Lankan State to their protest against the dump was to suggest that they leave their houses and relocate elsewhere within a week. In return, they were promised permanent housing within two years, and compensation up to Rs. 10,000 for rent until their permanent housing was provided. Furthermore, the protesters were offered the first three months’ worth of compensation as an initial lump sum. For some sections of Colombo residents, this solution may appear to be a fair and reasonable one.

For residents who possessed deeds and had lived in this area for decades a solution such as this was as risibly large as the growing garbage dump in their backyards. Why would we give up our permanent houses which we have lived in for decades for the promise (rather than guarantee) of permanent housing in the future and for such a ridiculously small amount of money in the meantime, they asked. Would residents in Colombo 7 be willing to do the same, they demanded to know.

As their questions demonstrate, this response by the State to their plight only served to further underscore their sense that they were but one of the unfortunate sacrificial lambs being led to the altar of modernisation and development for a ‘world class city’.

Their major sense of injustice here stems not from being left behind in the drive to develop and beautify Colombo city but to ask why they should be the ones to bear the cost of this development. They had seen how the garbage from Colombo such as poultry entrails were often strewn around their gardens by birds. They were acutely aware of how the expansion of walking tracks and exercise opportunities for residents of Colombo was only possible because of the respiratory illnesses that their children suffered.

They could not help but juxtapose the much-touted openings of high-class restaurants in Colombo with the difficulty they faced in attempting to consume the meals they cooked due to the powerful stench emanating from the dump. In short, their concerns about the dump were not about proper waste management but about the injustice of being forced to bear the cost of maintaining someone else’s privilege.

A telling response?

According to the survivors of the collapse, there were broadly three types of responses to their campaign to stop the dumping of garbage. The first type of response was to ignore protest all together in the hope that it goes away. The second response shared with us was the strategy to co-opt or buy-out key movement leaders to take the wind out of its sails. When these strategies failed to yield the desired results, area residents charge that the final type of response was violence.

The protesters faced the full wrath of the state with tear gas, water cannons, and batons used to break up protests. When this state mandated violence was inadequate to get the message across, residents reported that gangs of thugs were also used to beat them up in order to highlight the deadly seriousness of those who wished to maintain the garbage dump.

Sharing their experiences of this violence with us, these residents commented on the injustice of discovering that the very people who had assaulted them had also gone on to make police entries against them on the grounds that they had been beaten up by the protesters.

Garbage as black gold

Why was there such a strong commitment to maintaining this garbage dump in the face of spirited protest from area residents? The survivors of the collapse drew our attention to the way in which corruption lubricated numerous activities relating to waste management.

Among many other issues, they flagged the commissions earned on the use of industrial machinery to distribute garbage as well as the black economy built around the scavenging of garbage at the dump. As they point out, rather than being an abject exercise in waste management, garbage collection is in fact an extremely shady catalyst for wealth creation.

These residents continue to seethe with anger and resentment at the injustice of having seen how the accumulation of black capital through garbage collection was at the cost of the lives of their loved ones and the loss of their homes. They contrast the paltry sum offered by the State as compensation for the loss of their homes with the millions of rupees that were made through the maintenance of the garbage dump.

Unsurprisingly, they see the massive economic gains made by certain elements at their expense as a key contributory factor to the foot-dragging by authorities who had the power to avert the tragedy that took place a year ago.

A year since the collapse of the garbage dump, it is worth asking whether the political and economic conditions that contributed to the growth of the garbage dump have been adequately addressed in the rush to improve waste management.

The problem of justice

It is impossible to capture the depths of anguish at the loss of life and limb experienced by these survivors in a short article such as this. But their narratives about the factors that led to this tragedy teach us an important lesson.

Although attempts have been made to improve waste management, in the year since this tragedy took place, the question regarding justice for those affected by the collapse continues to be forgotten. In fact, the emphasis on waste management (while important) may help to mask and side-step our own complicity in maintaining a system the cost the lives of thirty-two people who were in the midst of celebrating the dawn of a new year.

How then can we contribute to the achievement of justice for those who lost their lives and for those who continue to survive the ill-effects of the garbage dump each day? We can begin by paying attention to the ways injustice is propagated by a system that values beautification over tragedy, accumulation over health, and development over life. We can examine our own complicity in perpetuating this system as long as it stands to benefit our social circle and immediate environs.

Starting with this in this new year may be the only way to ensure that the real tragedy of injustice that runs through our social fabric is not buried forever.

(The writers are researchers attached to the Social Scientists’ Association. These views are their own.)