Sunday Feb 22, 2026

Sunday Feb 22, 2026

Tuesday, 8 September 2020 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Sunimalee Madurawala

The COVID-19 pandemic is having an unprecedented impact on labour markets around the world. Globally, it is estimated that the number of hours worked will fall 14% in the second quarter of 2020, compared to the last quarter of 2019, due to workplaces shutting down and downsizing.

This is equivalent to 400 million cuts in full time jobs. Losses in working-hours indicate shorter work days, furloughed workers, unemployment, underemployment, and inactivity (withdrawal from the labour force). Data indicate that women are more likely to lose their jobs, compared to their male counterparts. Women are overrepresented in high-risk jobs, such as in the informal economy and in the service sector.

Due to the pandemic, countries are compelled to introduce social distancing measures, lockdowns, and mobility restrictions. In response, businesses have begun to adopt options of working-from-home (WFH), remote working, telecommuting, and flexible working hours, on a larger scale. In Sri Lanka too, many firms started to adopt such measures.

Encouragingly, Sri Lanka’s public sector also introduced WFH to ensure a smooth functioning of public services. These options help to solve major issues affecting women’s participation in economic activities. In this context, this blog discusses key challenges Sri Lanka faces when adopting WFH as a solution to the country’s low female labour force participation (FLFP) and proposes policy solutions to overcome them.

Working women and working from home

WFH offers a range of benefits and opportunities to both employees and employers. While employees benefit from zero commuting time and costs, lower stress, less work-family conflicts, more flexibility, more time to care for dependents, and higher job satisfaction, employers can take advantage of reduced overhead costs, increased margins, lower turnover, and a greater pool of talent.

Research shows that working women, especially working mothers, stand to benefit more than men from adopting flexible working options, such as WFH. Such arrangements help boost employment rates among mothers. Countries like Sweden and Denmark, which have the highest shares of women WFH, also boast of the highest maternal employment rates; however, no such correlation emerges for men.

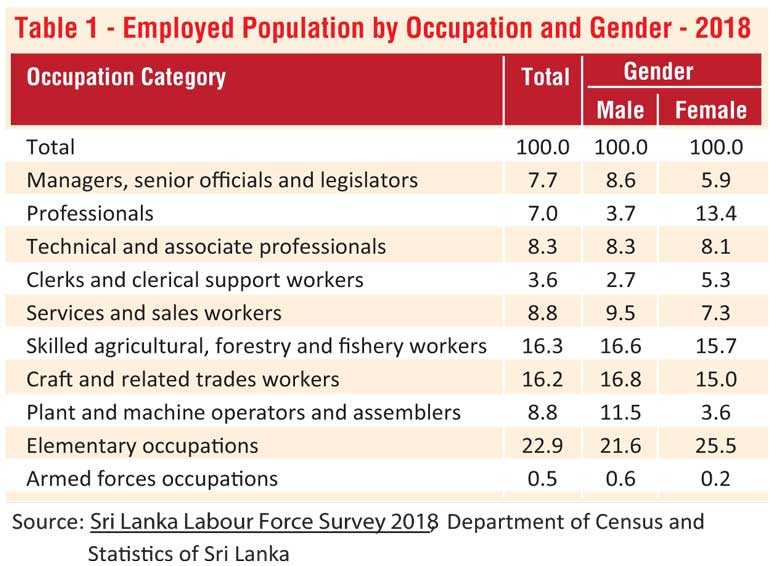

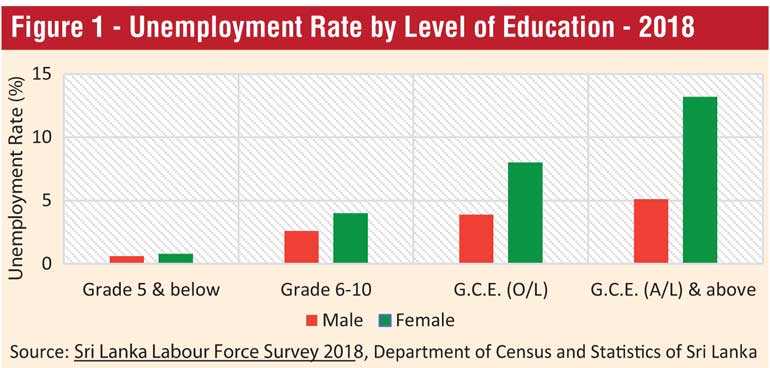

WFH is being recommended as a policy solution to increase the FLFP in Sri Lanka. The pandemic is giving the country an opportunity to test the feasibility of adopting it in the long run. In Sri Lanka, the FLFP has been stagnating at around 30-35% for many years; for males, it is around 75%. The unemployment rate is also higher for women compared to men, and the gap is especially prominent among those who have higher levels of education (Figure 1).

Challenges in adopting WFH

Unfortunately, Sri Lanka faces significant challenges in adopting WFH, especially for working women. It is important to consider the types of jobs females occupy and the feasibility of adopting WFH for those occupations.

The major job categories, with more than 10% contribution to total female employment, are ‘elementary occupations’ (includes cleaners, helpers, and labourers), ‘skilled agricultural, forestry and fishery workers’, ‘craft and related trades workers’, and ‘professionals’ (Table 1).

Except for the ‘professional’ category, practical difficulties remain in adopting WFH for the others. Even many occupations that come under the ‘professional’ category are difficult to do in a home environment (e.g., science, engineering, and technical professionals who need to have certain lab facilities to carry out their work, health professionals, and professionals working in the field of law).

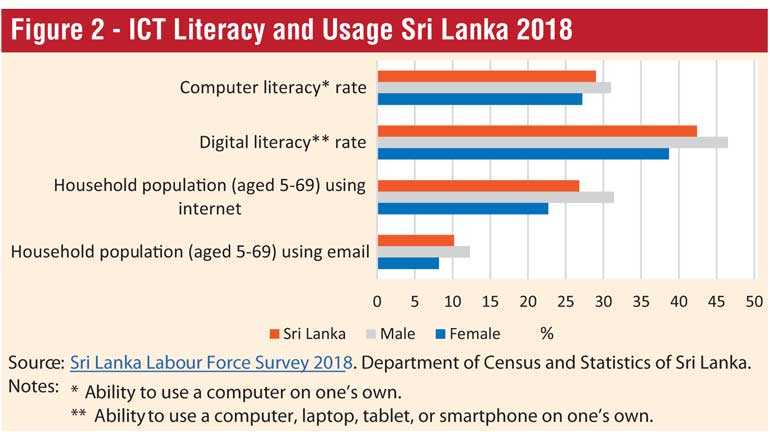

Moreover, telecommuting (i.e., making use of the internet, email, and telephone) is an essential element of WFH. Information and Communication Technology (ICT) plays an essential role in promoting WFH. Sri Lanka ranks 83 out of 121 countries in the Network Readiness Index (NRI) 2019. Further, only 22 % of households in the country owned at least one computer or laptop in 2018.

Figure 2 indicates that Sri Lanka’s overall computer and digital literacy rates are not satisfactory. More importantly, it also highlights the gender digital divide (the relatively disadvantageous position of women in accessing technology products, the technology sector, and digital skills education) prevalent in the country.

It is also vital to ensure that WFH will not place additional pressures on working women. Women who bear the brunt of care work will be further burdened if they have to meet their employment obligations at home. There can be conflicts owing to the employer’s and family members’ unrealistic expectations of a woman WFH. The employer may expect a WFH woman to work at a stretch, as if she was in office, whereas the family may think she can handle the household chores, as if she was on leave.

Moreover, often the family tends to expect a woman WFH to strike a better balance between household responsibilities and work, while a man engaged in WFH is expected to focus more on work. In such a context, time management can be an issue, and greater flexibility simply translates to greater stress.

The way forward

That said, even though there are practical difficulties in adopting WFH, Sri Lanka should capitalise on the opportunities presented by the current situation. The sectors that have more prospects of adopting such arrangements (such as ICT, professional services, the public sector, and finance), should be encouraged to practice WFH in the long run.

Further, WFH can be used to offer employment opportunities to more educated, unemployed females in such high potential industries. For employees, it is crucial to provide initial training on how to be successful in WFH with time management, balancing home and work.

Transitioning away from the traditional, time-oriented way of measuring productivity and adopting task-oriented evaluation methods are essential for a successful WFH model. It is important to facilitate individual companies to test and identify the approaches that work best for them to facilitate WFH and encourage female employees to reap the maximum benefits of WFH.

If Sri Lanka is to adopt WFH to increase FLFP, issues in ICT infrastructure and the gender digital divide should be considered as areas in need of immediate attention. In this regard, enhancing access to and improving the affordability of digital technologies, to cultivate ICT skills of employed females are of utmost importance.

These can be invested upon to upgrade the ICT infrastructure of the country and thereby, to narrow the gender digital divide. Further, addressing normative barriers and beliefs and overcoming stereotypes and biases are important in closing the gender digital divide.

Note: This blog is based on IPS’ forthcoming ‘Sri-Lanka: State of the Economy 2020’ report on ‘Globalisation and Disruptions: Reviving Sri Lanka’s Economy COVID-19 and Beyond’.